sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - may/june 2011 - innovate: forecast: profitably sunny

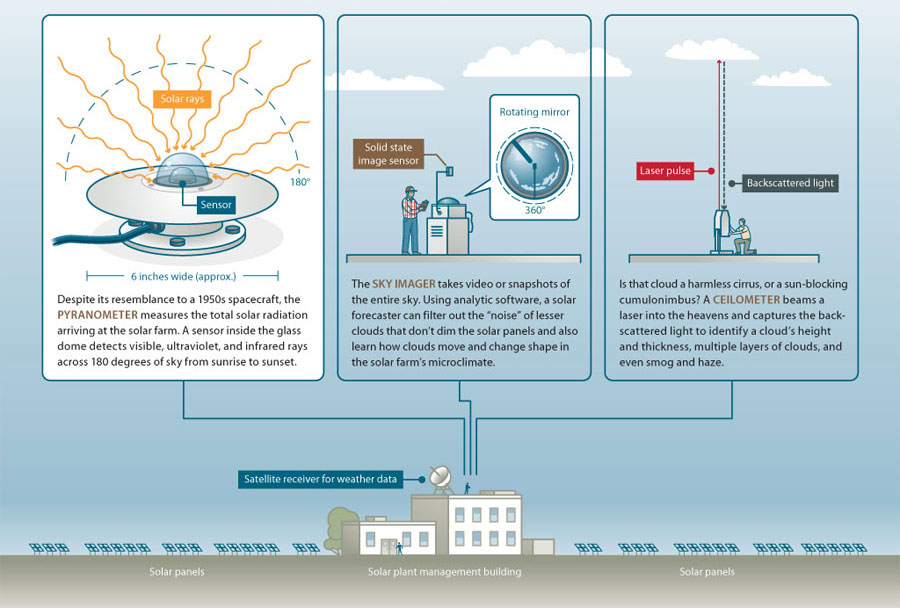

Pick a cloud on the horizon and try to guess whether it will eventually cover the sun. Then guess exactly when the cloud will pass overhead and how long it will be before the sun comes out again. This game becomes a profit-sapping frustration if you're the manager of a solar farm, when a partly cloudy day could lose you precious megawatts. Enter the new field of solar forecasting, which enables solar plant engineers to combine satellite and weather station data with detailed information on local sun and shade. It's all processed through a complex algorithm, so the plant manager, at least, can have fewer clouds over his or her head.

Infographic: Brian Kaas

Cloud Watcher

Carlos Coimbra does his most dangerous solar forecasting off the job, while astride his motorcycle. Crossing the Nevada desert on Interstate 15, he watches the thunderclouds on the horizon and wonders whether he should seek cover or risk playing slip-and-slide with the semis in the rain.

Carlos Coimbra does his most dangerous solar forecasting off the job, while astride his motorcycle. Crossing the Nevada desert on Interstate 15, he watches the thunderclouds on the horizon and wonders whether he should seek cover or risk playing slip-and-slide with the semis in the rain.

As the head of the Solar Forecasting Laboratory at the University of California at Merced, Coimbra makes other predictions for high stakes. One of solar power's biggest weaknesses is that it's intermittent, which makes it hard to compete in price or reliability with coal. But he says he may have a work-around.

Coimbra, a computer whiz, earned a Ph.D. in engineering with a specialty in fluid mechanics and physical modeling. The ability to think in 3-D came in handy when he landed a job at the University of Hawaii, which included modeling the interaction of waves and coral reefs. "I was completely happy and could have lived there forever," he says. But then something better came along.

That opportunity was the brand-new UC Merced, where the sun scorches flat Central Valley fields, all the buildings are LEED certified, and 20 to 30 percent of the campus's power comes from solar panels. It was the perfect venue for Coimbra to try new techniques for predicting the complex interaction of clouds and sun. He processes as many as 16 variables, from cloud height to humidity to photos to satellite images—and can predict when the sun will shine during the next hour with 90 percent reliability.

Coimbra helped to establish solar forecasting stations at UC Davis and Berkeley and hopes to foster hundreds of others to make California's solar supply as predictable as a UPS delivery. He also forecasts that this summer he'll take bike rides with his daughters in the early mornings and evenings to avoid what he calls Merced's "massive solar irradiation"—what the rest of us might call stinking heat.

—David Ferris