sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - sept/oct 2011 - last man standing

Why fight like hell for a town that others have given up for lost? Because it's yours.

By Bruce Selcraig | Photography by Matthew Turley

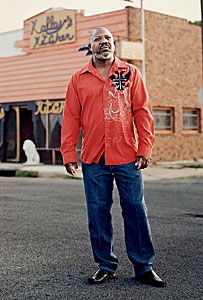

Activist Hilton Kelley is proud of his soul food restaurant and his hometown of

Port Arthur, Texas: "We have a culture here. Great food, music, Mardi Gras."

Activist Hilton Kelley is proud of his soul food restaurant and his hometown of

Port Arthur, Texas: "We have a culture here. Great food, music, Mardi Gras."

Outside Kelley's Kitchen, an enticing soul food joint in the coastal refinery town of Port Arthur, Texas, you can carry on a conversation in the middle of Austin Avenue's four broad lanes and have little fear of being hit by anything stronger than a warm breeze off the Gulf of Mexico.

At the far end of the street sits a deserted post office and the once-proud World Trade Building, its six concrete-and-steel floors vacant since the 1980s. Past the restaurant's neatly trimmed yard, in a landscape that feels like New Orleans's Ninth Ward, weed-covered lots and boarded-up stores flank ravaged wood houses whose gaping roofs still sport blue FEMA tarps installed after Hurricanes Rita (2005) and Ike (2008). Just blocks away, acts like James Brown and Al Green once played to packed auditoriums. Now the town has a per-capita annual income of less than $17,000. A quarter of its 56,000 residents live below the poverty level.

Inside the restaurant, laboring over her okra and smothered chicken, Marie Kelley hardly needs to justify why they stay open only until 4 p.m. "There's not much of a dinner crowd down here," she says, nodding to the blighted boulevard most folks want to avoid after dark.

"You bet I carry a gun, a .40-caliber semiautomatic," declares Hilton Kelley, Marie's husband and the restaurant's owner. "I used to live in Oakland [California], spent four years in the Navy, but I never carried a gun until I came home to Port Arthur. And when I told everyone here I was gonna start packing," he cackles, "they were like, 'What? You don't carry a gun?' Turns out I was the last of the unarmed Mohicans."

Eight major petrochemical and hazardous-waste facilities spew emissions into Hilton Kelley's neighborhood.

Built like a linebacker and partial to sandals and bright Caribbean threads, the North American recipient of the 2011 Goldman Environmental Prize (and its coveted $150,000 check) whips out his laptop and hollers sweetly at Marie to fire up a cheeseburger. Kelley's agitated sinuses keep him sniffing and wheezing while he peruses data on the Gulf Coast's elevated cancer rates—the price, many Texans feel certain, of living downwind from dozens of plants spewing carcinogens such as benzene, 1,3-butadiene, and styrene. He glances at a Royal Dutch Shell whistle-blower's blog. He reminds himself to pay his gas bill.

A local nicknamed Shaq comes to Kelley's for some advice on community block grants. A bleating cell phone brings another national reporter inquiring about the environmental record of the nearby Huntsman chemical plant. Between intrusions, a bio worthy of the big screen emerges:

Born by a midwife in Port Arthur's Carver Terrace housing projects to an absent 19-year-old father and a struggling 17-year-old mom. . . . Mother later shot point-blank in the temple in 1979, Kelley says, by a local man who escaped prosecution. . . . As a teenager he saw an all-black performance of Othello at Port Arthur Lincoln High and vowed to make it in Hollywood, which he did, working as a double and stuntman on TV shows like Nash Bridges and Midnight Caller. . . . He returned to Port Arthur in 2000, after a god-versus-devil epiphany in Oakland, determined to clean up an array of multinational polluters that dominate life in the town Janis Joplin once called home . . .

A local Baptist preacher, Donald Toussaint—who did gang intervention on Chicago's South Side—drops by Kelley's to discuss his church's new social justice program.

"Good luck, Preacher," offers a cautionary Kelley, himself a regular at another Port Arthur church, St. John Baptist. "I'm all for what you're doing, don't get me wrong. Faith without works is dead," he says, quoting James 2:17.

"Lotta folk wanna pray," Toussaint agrees, "but not protest."

"Come on, amen," Kelley says, easing into the rhythms of Sunday. "I tell people it's time to get up off your knees and roll up your sleeves."

Kelley tells Toussaint to expect resistance from a black community that he says can often be naive and passive. "Seven, eight years ago," Kelley says, "I would go to some of these black churches and just ask if I could pass out some informational flyers about refineries and chemical emissions. And they'd say, 'We don't want none of that in here, son.'" (The plants employ members of the congregation.) "And don't even get me started on the NAACP," he adds. "They're nonexistent. I've had a ton of support outside my race—Neil Carman, a chemical expert with the Sierra Club, has been a mentor to me; Denny Larson, who runs Global Community Monitor, in California, has taught me many things—but the very people who you are fighting for the most got to wake up and help themselves."

Kelley is on his third marriage. "I can be bullheaded," he admits. "I'll tell you when I'm not happy." He loves to dance, met Marie at a social club that has "swing out dances"—"it's a southeast Texas black thing." . . . He loves his Tanqueray gin, has three kids in their 20s. . . . A former Eagle Scout and Navy electrician, he got through the lean times of activism by doing home repairs.

Kelley's environmental campaigns in Port Arthur—that's Poat Ahhthuh to natives—have won him a wall full of national awards and proclamations, but little help, he says, from the city's state and congressional leaders. Often through tedious negotiation or the threat of litigation, Kelley's organization, Community In-Power and Development Association (CIDA), fought for a public alarm system for refinery accidents (rather than emergency responders simply telephoning one another); kept a local toxic-waste incineration firm from importing PCBs from Mexico; and stalled the expansion of a Motiva gasoline refinery for a year, until its owners, Royal Dutch Shell and Saudi Petroleum, vastly upgraded its technology, signed a "good neighbor" agreement, and donated $3.5 million to the community.

When it goes on line next year, the expanded refinery will be the largest in North America, producing 625,000 barrels a day. Kelley hopes Motiva will, as promised, hire more Port Arthur residents. "Overall, I think Hilton has been a positive force for change," former Motiva plant manager Tom Purvis says. "He's not trying to run us out of business."

With help from Carman and Larson, Kelley also learned how to operate $65,000, handheld air-quality monitoring devices called UV Hounds, which revolutionized his work and removed the need to wait on Texas's overwhelmed, underfunded environmental cops to do their jobs.

"It was like putting a gun on Wyatt Earp," says Carman, a former state environmental inspector who works out of the Sierra Club's Austin office. "Hilton can now take instantaneous laser measurements for chemicals like benzene and butadiene. The big problem is that air-toxics monitoring like this is just a joke in America. No refinery in the U.S. has a mandated laser-monitoring system." The UV Hounds put activists like Kelley in the once undreamed-of position of knowing precisely what those plants are releasing when they report refinery "upsets" to environmental investigators.

Kelley, who traveled to the Netherlands, England, and South Africa to put pressure on Royal Dutch Shell, joins Carman in crediting Motiva for crafting an agreement they say could become the model for future industry-community pacts. Motiva's $3.5 million donation—still a mere .05 percent of Royal Dutch Shell's $6.9 billion profit in just the first quarter of 2011—will go to a number of grants that address Port Arthur's problems in education, housing, job training, and health; Kelley applied for and won some $40,000 to help start his restaurant. "Still, Hilton has a very long, hard row to hoe in Port Arthur," Carman says. "The town is a mess, and he's been hitting his head against the wall for a decade. These fights are very hard in the South."

As we cruise Port Arthur in Kelley's black SUV—past the large red and yellow Vietnamese Buddhist temple (a former Catholic church), the photo ops of playgrounds near refinery fences, and a mural of the town's nationally acclaimed rappers, UGK, or Underground Kingsz—he points out the old convenience store where his mother was shot. "It was the '70s," he says. "Cops ignored a lot of black-on-black crime."

That Kelley doesn't harangue a white Texan about the legacy of racism in our state speaks to his rural hospitality and an understanding that it may be too simple an explanation for a world-famous environmental activist to give. He assumes you already know that the town of Vidor, for decades an outpost for the Klan, is just 30 miles away, and not far from Jasper, where in 1998 a black man, James Byrd, was chained behind a pickup truck and dragged to death by prison-bred white supremacists.

Far more common than overt racism these days is the surrounding white communities' dismissal of any suggestion that Port Arthur may have been victimized by negligent, mendacious polluters for reasons of greed, class, or color. Kelley is unfazed when I mention that a 40-year-old white Methodist church secretary who lives outside Port Arthur explained to me earlier that day that Kelley's virtually all-black, west-side neighborhood—she had never heard of him—used to have more whites but that they moved when it was taken over "by thugs, drug dealers, and people who don't mow their lawns."

The mother of two, who asked that her name not be used, offered: "They just don't care. They don't wanna work. It has nothing to do with the refineries. If they really wanted to, they could move. If our air is so bad, why do we have so many old people?"

Kelley can somehow laugh at the woman's unreconstructed rhetoric, but don't think he hasn't given some thought to her solution—moving. "Lots of people I know have tried, but they always come back," he says, waving howdy to a local standing outside a boarded-up Walgreens. "We have a culture here—black people, I mean—great food, music, Mardi Gras . . ."

Right on cue, a group of seven teenagers, backpacks in tow, on their way home from school, pass an older man mowing his lawn, as the sun edges below the silver steel refineries.

"See that there?" Kelley says, beaming at the Hallmark moment. "These are my people. They were my teachers, my coaches. They go to my church. These could be my own kids. I really need to be here."

BRUCE SELCRAIG, a native of the Texas Gulf Coast, lives in Austin.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Environmental Justice and Community Partnerships program.