sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - july/august 2012 - innovate-ocean-thermal-energy-conversion - innovate: it came from the deep

By David Ferris

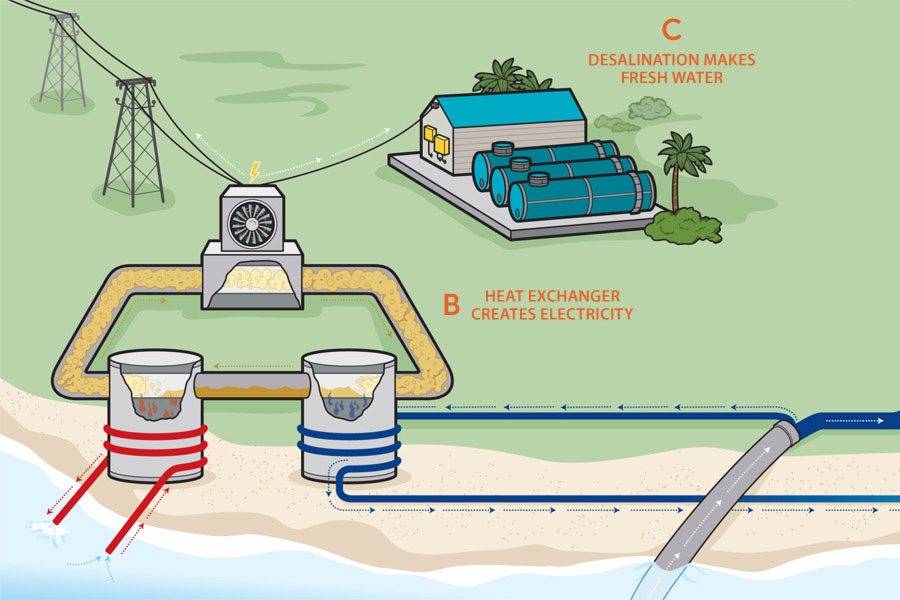

B: The warm water is circulated through a heat exchanger alongside liquid ammonia, a process that vaporizes the chemical. The ammonia steam flows through a turbine, which spins a generator to create electricity. The vapor then heads into another exchanger, where it is cooled by the cold water pumped from the deep. The ammonia condenses back into liquid, and the loop starts again.

C: Electricity generated from OTEC can be used to light a city. On parched islands, it can also be used to desalinate seawater—preferably that deep cold water, which often requires less electricity to be turned into much-needed freshwater.

Deep Thinker

For nearly 25 years, Ted Johnson has waited for the world to wake up to the opportunity of using cold water from the deep seas to make cheap electricity. Now the goal is tantalizingly close.

For nearly 25 years, Ted Johnson has waited for the world to wake up to the opportunity of using cold water from the deep seas to make cheap electricity. Now the goal is tantalizingly close.

Johnson got his introduction to ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) in the late 1980s, when Lockheed Martin hired him to direct its ocean ventures. He was captivated by OTEC's promise of supplying two things that islands often lack: fuel and water.

In 1979, when the Arab oil embargo sent gas prices skyward and the Carter administration was throwing money at alternative-energy research, Lockheed built an experimental OTEC plant off the coast of Hawaii. Hopes were high, and indeed the plant worked flawlessly during its three-month trial run. A decade later, several companies built another one onshore that produced 250 kilowatts, five times as much electricity as the first plant.

But then oil got cheap again, and the world yawned. "I kept a candle in the window," Johnson says of his faith in the technology during the following two decades. Unsatisfied with the pace of development at Lockheed, he jumped ship in 2011 and joined Ocean Thermal Energy Corporation, where he serves as senior vice president. Last September, the company reached a tentative agreement with the Bahamas to build a pair of 10-megawatt OTEC plants. Scheduled to be completed in 2014, they will be the world's first commercial-scale OTEC facilities.

Prospects for deep ocean power have improved drastically since the 1970s. Pipes and turbines have become much cheaper, and island leaders, drawn by the prospect of self-sufficiency and worried about spikes in oil prices and rising sea levels from climate change, are showing interest. Johnson is in talks with several Caribbean, African, and Pacific nations, as well as the U.S. Navy—which wants a gigawatt of renewable power for its bases by 2020.

"When we flip the switch on this plant in the Bahamas, the world has changed," Johnson says in the flat tones of his native Illinois. "At 68, I'm just starting what I want to do."

Illustration by Brown Bird Design