sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - nov/dec 2012 - plugged in

Electric cars get ready to take over the road, quietly and powerfully

By Reed McManus

Driving a Ford Focus Electric around San Francisco was startling. Startling in that no one noticed. Here I was, slipping along city streets in a car that relies on no gasoline, no ExxonMobilShellChevron supply chain, no terror-fomenting oil country, and I might as well have picked up my white four-door at the Hertz counter at the San Francisco airport. Except for its unique Aston Martin-ish front grille and a few demure badges, the electric Focus looks like a standard Focus. At least with the oddly shaped hybrid Toyota Prius and the all-electric Nissan Leaf, a driver's green credentials are billboarded. Did I have to roll down the window and shout?

But anonymity is the new point. If the United States hopes to reduce its reliance on greenhouse-gas-spewing fossil fuels—the Sierra Club's goal is a 50 percent reduction in oil use by 2030—alternatives to gas swillers have to become mainstream. President Barack Obama wants to see a million electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles on the road by 2015. Yet only about 20,000 Chevy Volts, the most popular plug-in, were sold in the past two years. Total U.S. auto sales in 2012 alone are expected to surpass 14 million. So there's a distance left to travel.

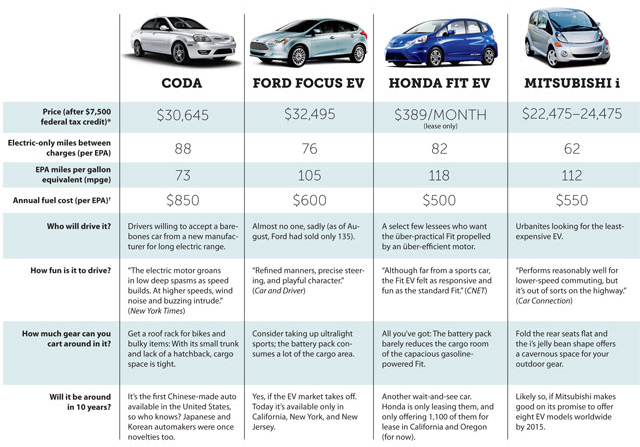

Download the chart at full size.

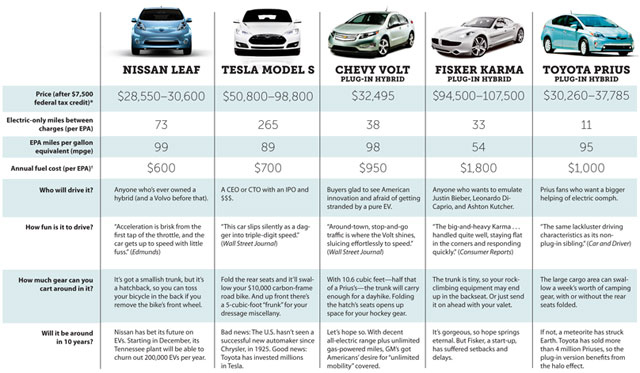

Fortunately, the trip is well under way. As of press time, you can select from at least six all-electric vehicles. (See chart, above.) In addition, three plug-in hybrids (the Chevy Volt, Fisker Karma, and Toyota Prius Plug-in) allow you to drive a nominal number of miles on electric power alone before a small gasoline engine helps out. (With traditional hybrids like the popular Prius, the gas engine and electric motor work in tandem, so you rarely drive gas-free.) Another six carmakers have EVs scheduled for release in the near future.

What will it take to get millions of drivers to plug in? For car buyers not necessarily motivated by World Resources Institute climate-change studies, there's this enticement: Electric vehicles offer all-American driving fun. When you push the compact Focus's accelerator to pass a car on the freeway, it feels like you're driving a larger BMW or a Mercedes. That's because EVs have lots of torque: All the power of the electric motor is available the moment you press the gas pedal.

Download the chart at full size.

All-electric vehicles are also eerily quiet: With an electric power train, there's no engine revving or gears shifting—just forward motion. (An electric car's motor converts 60 percent of the current it receives from the utility grid into forward motion, compared with 20 percent efficiency for a gas-powered engine.) They are so quiet that carmakers have had to engineer software-generated sounds to alert unsuspecting pedestrians and cyclists of an approaching EV.

And they are cheap to operate, costing 2 to 3 cents per mile, as opposed to 15 to 16 cents per mile for a gas-powered car. The EPA calculates the miles per gallon equivalent (mpge) of electric cars, which is not the amount of miles you can actually drive before recharging but rather a way to compare the efficiency of apples (plug-in cars) and oranges (gasoline-powered cars) using the familiar miles per gallon rubric. The mpge of all-electric vehicles—from 89 for the Tesla Model S to 118 for the Honda Fit EV—makes a standard Prius, which is rated at 50 mpg combined, look like a fuel-economy poseur.

1 | 2 | next >>