sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - jan/feb 2013 - solar for all

Until now, rooftop solar has only worked for those with hefty electric bills and sunny roofs. Community solar could make it available to everyone.

By Paul Rauber

Ready financing would be a big boost for community solar—or any kind of solar, for that matter—but it can't take the place of smart public policy. A good example is the 2010 legislation in Colorado that created the opening for solar gardens. It took the state's public utility commission almost two years to write the necessary regulations, so it wasn't until last August 15 that Xcel Energy, the state's largest utility, started accepting applications to build them. Xcel shut the process down in 30 minutes, after receiving proposals for three times the 4.5 megawatts released in this round of the program—most of them from the Clean Energy Collective.

Even more striking are the policies enacted in Germany, which boasts more than a million solar systems, four times as many as the United States despite the fact that it has about one-fourth of the population. Last May 26, these mostly rooftop arrays produced 22 gigawatts—enough to meet half the country's electricity demand. It's worth noting that the "insolation," or sunniness factor, of Germany is worse than that of everywhere in the contiguous United States except rainy Seattle.

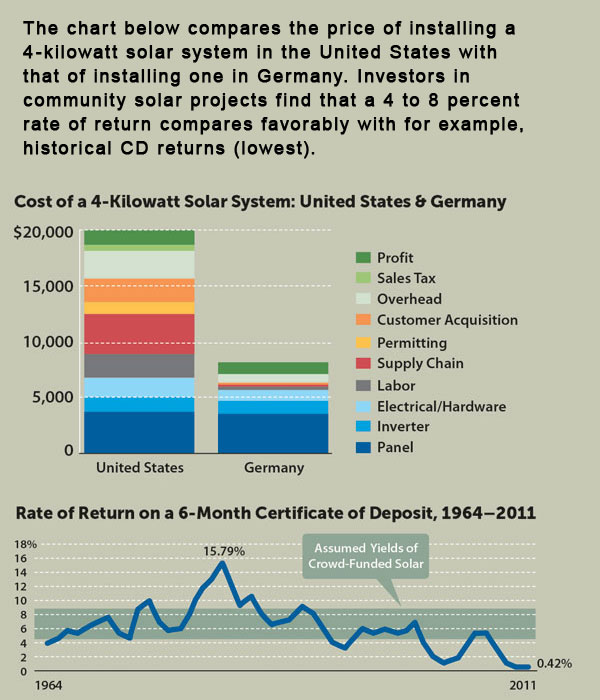

What does Germany have going for it that we don't? For starters, Germans have focused their famous efficiency on cutting costs. Installing a rooftop solar array in the United States costs about $20,000, but in Germany it costs about half that—because nearly every element of the transaction is simpler and cheaper. In the United States, cities typically require reams of permits, with regulations and fees varying widely from one town to the next. (In California alone, permit fees range from nothing to $888.) In Germany there are no fees, and only a simple, one-page online registration is required. There's also no sales tax for solar installations, and permission to connect your system to the local utility is a given.

Even more important, Germany subsidizes solar power by guaranteeing a fixed price plus a reasonable rate of return—a policy known as "solar cash back" or "feed-in tariff." That makes solar a solid, simple investment—one as secure as a savings account. The annual rate of return declines over time, which encourages people to install their systems sooner rather than later. It also creates pressure on solar installers to become more efficient and to cut costs, so solar investors can get the most out of their euros. Gainesville, Florida, has such a policy; consequently, Mosaic is seeking to develop community solar projects there. Los Angeles is using its feed-in tariff—which was cosponsored by the Sierra Club—to help it get to 300 megawatts of rooftop solar by 2016.

Were he made U.S. energy czar, Farrell says, his first move would be to institute a national feed-in tariff: "Then you don't have to mess around with anything else." Of course, one might wish for a tax on carbon too, but neither policy is very likely in the current political environment. A more probable path to widespread community solar is to improve—or at least extend—the existing federal tax credit for solar installations. That credit expires in 2016, and any solar developer who watched Congress gridlock over extending the tax credit for wind has to be getting the heebie-jeebies. "Without the tax credit," says the Clean Energy Collective's Spencer, "these things do not work."

That doesn't mean, however, that the credit needs to stay exactly as it is. The current system is tailored to banks or large investors who have big tax liabilities. Thus, small and mid-level developers end up selling their credit to banks at a big discount. So, Farrell says, if the tax credit were replaced by a cash grant, the financing of community solar projects would be much simpler and more efficient. Also, he says, "the federal government would get a lot more bang for its buck out of a cash option because people wouldn't need a middleman." While a grant system may not sound politically likely, Congress actually enacted such a program from 2009 to 2011—a $9 billion effort that enabled 23,000 clean energy projects, enough to power 3.4 million homes.

Another way to boost solar, wind, and renewable energy of all stripes would be to establish or increase statewide renewable energy standards (a.k.a. renewable portfolio standards), which dictate the amount of clean energy a state's utilities must provide by a certain date—20 percent by 2020, for example. They're what give utilities an incentive to buy solar power in the first place. Thirty-three states and the District of Columbia currently have such standards, 16 of which require that a certain percentage of that clean energy be solar. New Jersey, for example, requires a 4 percent solar share, and consequently has a high rate of solar installations.

As reasonable as such policies are, they're still a heavy lift. Last August in California, two bills that would have vastly expanded community solar were quashed by the state's powerful utilities. One, known as "Solar for All," would have established a small feed-in tariff to promote solar gardens and other renewable energy projects in low-income communities; the other would have let Californians purchase shares in solar facilities and get credit on their energy bill for the clean power produced. It could have added up to 2 gigawatts of power to the state's grid, but intense lobbying from two of the state's largest utilities—which complained that the power generated would not count toward their renewable-energy-standard goal—killed it in committee.

"Unfortunately," said the bill's author, state senator Lois Wolk, "PG&E and Southern California Edison control the committee."

Community solar doesn't have to be forced on utilities, as Colorado's Clean Energy Collective has shown, but it does represent a challenge to their business model. Absent a major feed-in tariff like Germany's, the solar panels you put on your roof are for your own personal use, with any surplus conveniently available to the utility at the time it needs it most.

But if my neighbors and I figure out how to launch our solar co-op, and the folks on the next block do the same, and the next block after that, eventually our utility is going to start running out of customers, and will exert what political juice it has to slow the process. But that can only last so long. Remember grid parity—when solar power becomes as cheap as or cheaper than electricity from fossil fuels? When that time comes, neither lobbyist nor bureaucrat will be able to hold back the clean energy tide, and the cat fanciers of Oregon Street will toast their bagels with sunbeams.

Paul Rauber is a senior editor at Sierra.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign

.

Graphics sources, from top: Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Bloomberg

The "Cost of a 4-Kilowatt Solar System: United States & Germany" graphic has been corrected.