sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - jan/feb 2013 - innovate: solar designs from nature

By David Ferris

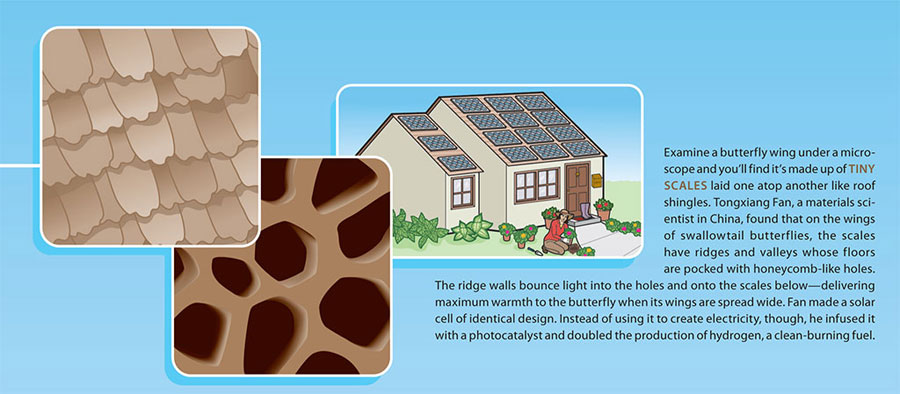

Examine a butterfly wing under a microscope and you'll find it's made up of tiny scales laid one atop another like roof shingles. Tongxiang Fan, a materials scientist in China, found that on the wings of swallowtail butterflies, the scales have ridges and valleys whose floors are pocked with honeycomb-like holes. The ridge walls bounce light into the holes and onto the scales below--delivering maximum warmth to the butterfly when its wings are spread wide. Fan made a solar cell of identical design. Instead of using it to create electricity, though, he infused it with a photocatalyst and doubled the production of hydrogen, a clean-burning fuel.

Fond of Fronds

One sunny day in May 2010, Jong Bok Kim sat outside his Princeton University office staring at a shrub. Kim, a postdoctoral researcher in chemical and biological engineering, wanted to find the best skin for a solar cell. Would the most electricity be produced by a surface of tiny strips, pyramids, or mirrors? Then he realized that the shrub held the answer.

One sunny day in May 2010, Jong Bok Kim sat outside his Princeton University office staring at a shrub. Kim, a postdoctoral researcher in chemical and biological engineering, wanted to find the best skin for a solar cell. Would the most electricity be produced by a surface of tiny strips, pyramids, or mirrors? Then he realized that the shrub held the answer.

Kim returned to his desk to read up on how leaves gather light. He marveled at their genius: The facade of a leaf is blanketed with transparent cells that work like magnifying lenses. And the microterrain is scored with millions of ridges that guide light rays deep inside.

Kim, 34, knew how to create a rough surface like that on the nanoscale; while in college in Seoul, Korea, he had worked on making better LED displays by tinkering with their molecular structure. So he created a solar cell skin that mimicked that of a leaf, and he measured how much light entered the cell. "I knew it would increase efficiency, but I didn't know by how much," Kim says. Surprisingly, his panel with the leaflike skin absorbed six times more infrared light than one with a flat surface.

To compound the usefulness, Kim conducted his experiment using a plastic solar cell instead of the usual silicon. These cells yield a fraction of the electricity but are far cheaper and can withstand stretching and bending. Plastic cells could make a flexible skin for, say, a backpack. Kim is tinkering with fabric that spends much of its life in sunshine--curtains. If draperies are meant to block light, he figures, those frustrated photons might as well be captured by a plastic solar curtain to create some useful electricity.

To make the solar curtain more powerful, he intends to go back and learn more from the bushes. "What could be better than a leaf?" he says.

Illustrations by Brown Bird Design