the john muir exhibit - life - at home with john muir

At Home with John Muir

by George Gerard Clarken

From: Overland Monthly, Vol 52, No. 2, August, 1908, pages 125-128

Download a PDF of this article from original Overland Monthly magazine.

John Muir belongs to California and California to John Muir. Muir is an inalienable asset, just as much as the poppy and the redwood, the climate and the flowers. Mr. George Gerard darken has given us a keen appreciation of Mr. Muir and his characteristics, a valuable addition to the chronology of famous Californians published in Overland Monthly from time to time. It is the editorial policy of this magazine to laud a man while he is alive rather than sing his praises after his death.

EDITOR OVERLAND MONTHLY. |

We of California, with our birthright of sunshine and flowers, are wont to accept the distinction with that complacency generally exhibited by any one whose earliest remembrance follows him unchanged through life, and are likely to pay scant heed to those benefactors of natural science who have brought us to a clearer understanding of our environment.

While unmistakably proud of the national reputation of California as a State of flowery profusion, we might go a step farther and glance into the lives of the men who have brought us in touch with nature and given to the world the result of their labors.

Perhaps the greatest natural scientist in the United States to-day, and to whom every cultured people of the globe are indebted, is John Muir, the Burroughs of California, who has come out of the deserts and mountains with geological and botanical treasures, and laid them at our feet that we might profit by his investigations.

John Muir's name has been spoken in every corner of the globe; indeed, during his travels he has minutely studied from the frozen wilds of far Alaska to the tropics of South America and Africa. And while he has been studied much in the same manner in which he studies, he has seldom been met in the quiet of his library or his garden, or while applying himself to those pleasure-duties which occupy him throughout the day, and at times far into the night.

Muir has been likened to Joaquin Miller, and the similarity in temperament and aim is closely akin. He possesses the same keen, dominant desire for shearing nature

of the prosaic and treating it as the most beautiful handiwork of creation, as does

the Poet of the Sierras. He would sleep in the fields that he might learn the flowers, or in the forests to be close with the trees as they tower above him. Beside a rivulet or on barren plain, in valley or in the deep solitude of mountain peak, John Muir is content. All are his companions, his earth-born studies holding out new possibilities with each visit, and appealing to him with a silent sympathy such as only years of close association can make possible.

While his literary efforts have seldom resolved themselves into verse, he writes with a wonderful mastery at his command, born of long years of study, concentration and affiliation with his subjects. Muir has spent years in the depths of the Yosemite forests, and years more in the desolate wastes of Arizona's deserts, communing with nature in her swaddling clothes, and studying, analyzing and noting. He declares the happiest days of his life have been spent on mountain side, in the sun-baked deserts or beneath the shade of a redwood grove. A blanket and a little food in the wilderness transform it into a paradise to John Muir, for he long ago allied himself with primal conditions, and made them his life study. What he begins at such times as he is away from

home, he completes in the quiet of his

spacious residence, surrounded by massive

and comprehensive volumes on geology

and the sundry phases of plant life.

Queer as it may seem, this venerable

man no longer regards his hearthstone

as a home, but purely as a place where he

may have those conveniences, which

are

not at his command in a tent on mountain

or plain. Save for the additional facilities

to be obtained for study, he and the four

walls of a house would be aliens, and, as

he apologetically remarked some time ago

to a man who said he was glad to see him

home again: "Why, this isn't my home.

It is on the mountains or in Arizona. I'm

simply here to secure that rest which my

body demands. I am getting old, you

know, and what was mere exercise a few

years ago is fatiguing exertion now." This

is the artist speaking in Muir, and when

it is known that he prefers a soughing west

wind to the melody of other music for his

De Profundis, it is not difficult to abide with him

In his selection of a home, Muir sought

to combine massiveness with simplicity, and at the same time preserve harmony

in the contrast. He chose the site for his

house in one of the most beautiful locations

in the Contra Costa Valley, where inspiration sighed with the winds and where he could perchance dream himself back to the Yosemite and fear no disappointßent

upon awakening.

Sheltered on one side by a wooded hill

and surrounded on three others by vineyard,

orchard and stream, overlooking

miles of rolling landscape, and in the

very shadow of towering Mt. Diablo, this

mansion commands a magnificent scope

of view. In the garden he planted countless

varieties of tree and shrub, and let

nature run riot in luxuriance. Pine and

palm and cacti bow to each other in the

breezes while the thousand scents of budding

fruit trees waft themselves incenselike

through his study window. A winding

walk of concrete leads around the

place through profusions of bloom and

fruit, and four stately tropical palms

stand sentinel like before his door.

Within, one is introduced to simple

elegance. The hardwood floors are hidden by rich Oriental rugs, and the reception room, with its immense fireplace and paintings of the Yosemite, proclaim the aged master of the place an artist by temperament and taste. No glaring monstrosities of the wood turner's art are to be seen in any corner, for he carefully planned the furnishings, and brought with him nothing that could not serve some end other than display. Two Morris chairs, a rocker, table or two, several pictures and bits of petrified wood on the long, narrow mantel-piece about the chimney, comprise the furnishings and combine the antique with the modern. But there are evidences of a more feminine hand in the appointment of the room than John Muir would perhaps care to have called his. Off in a corner is a settle almost hidden by handworked fancy pillows, one with the letters "U. C." worked in 'blue and gold, another with a painting of a California poppy, and still one more with a Gibson creation worked through the facing in silk and water color.

Let it be known here that John Muir does not live alone, nor study without a companion. The feminine touches were the work of Miss Helen Muir, daughter of the house, and a true product of the West. While we drew mental pictures of her, expecting the appearance of a young woman in fluffy creations of a stylish dress-maker, the Troy maiden entered frank, healthy-cheeked and with a firm tread, which bespoke an outdoor life. A blue army shirt, string tie, old skirt and heavy boots, gauntleted, and wearing the regulation cowboy hat, she stood before us with a grace 'of manner which would have put to shame her sisters of silks and satins.

Would Mr. Muir be interviewed? No, she hardly believed he would. But we might try. "There's nothing like making the attempt," she hastily temporized, with a laugh, and vanished to her father's study. While awaiting her return, we had ample time to study the scenes which unfolded themselves on three sides through the windows of the room. To the south lay the Santa Fe viaduct, the longest in California, piercing the hills on one end and losing itself in a tunnel on the other. Muir station, named after the aged naturalist some years before, stood oft' to the east, while the valley below, blinking in the early afternoon sunlight, wandered vagrantly to north and south.

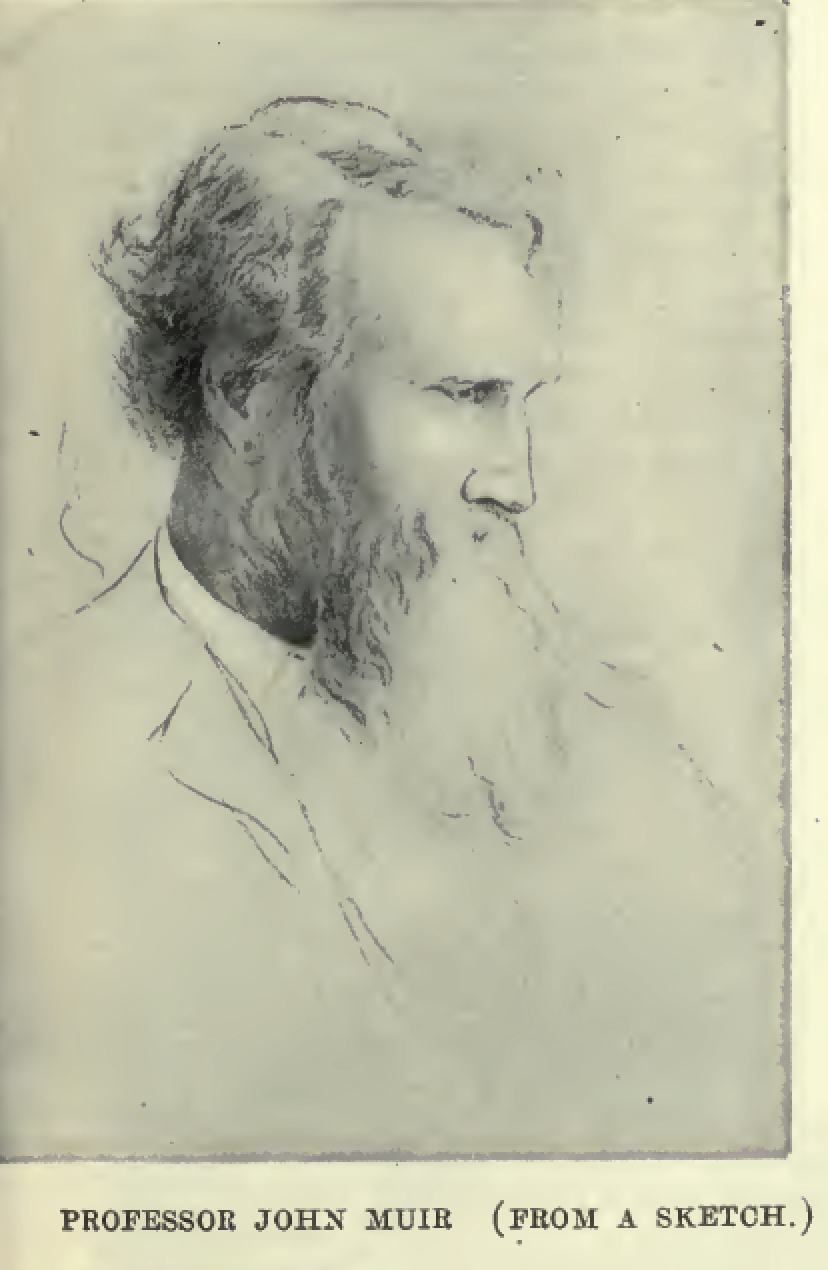

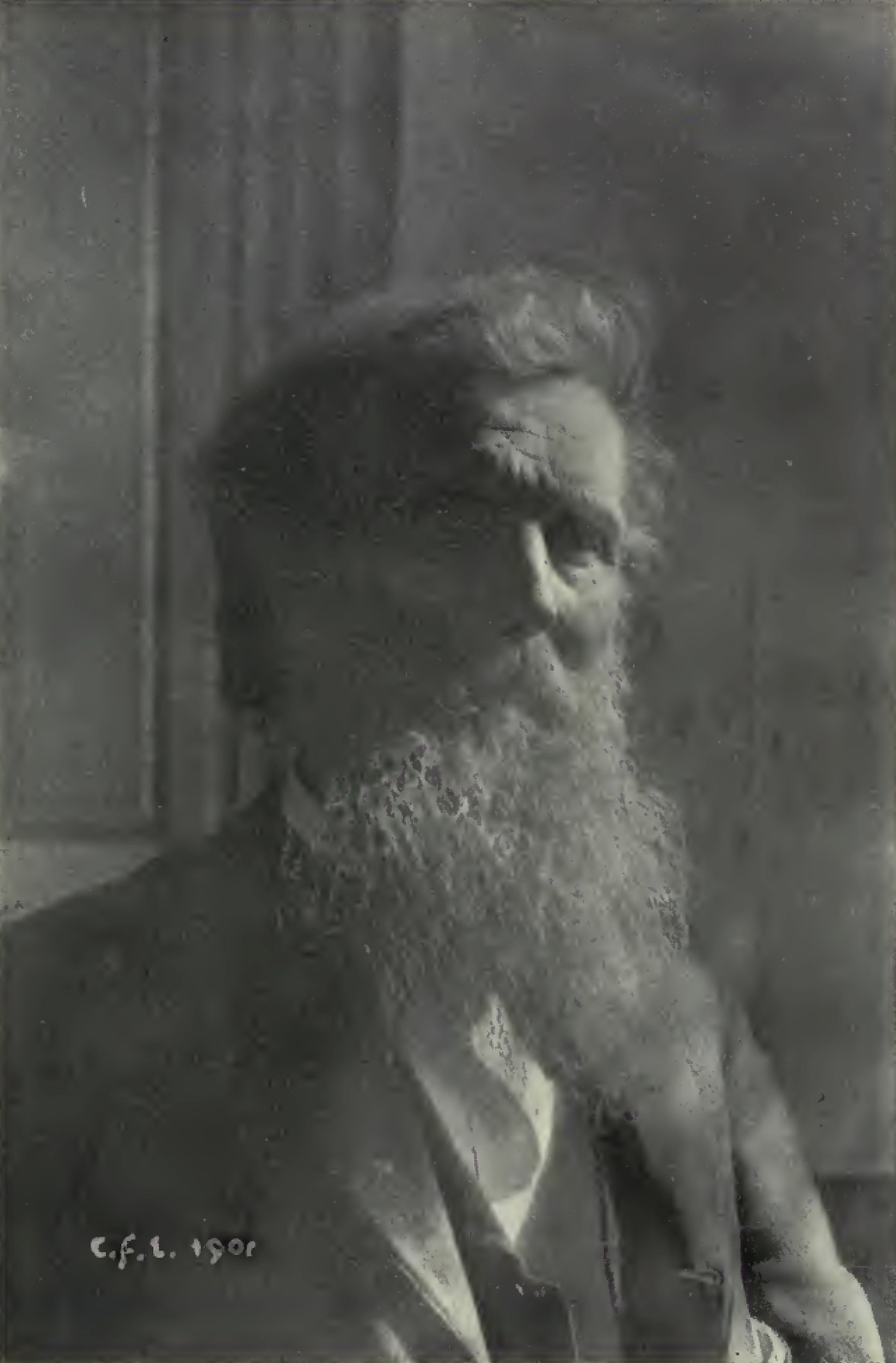

I will not soon forget my first impression of John Muir. Many times had I seen his photographs, but until now had never grasped his hand, a hand, by the way, as creased as his broad face, and still retaining a strength at 70 that many of half his age might envy. He was seated as we entered, and closely bent with microscope to his eye studying the formation of a bit of petrified wood. His greeting was hearty, his grip firm, and his words echoing a strange note. It was as though he had partaken of the strength of his subjects, as though the blood in his veins ran iron, and his eyes were of steel. There was a vigor and manhood about John Muir that stamped him as strong of mind as of limb, and possessing the full courage of his convictions.

His face must appeal to any student of human nature seeking facial expression, of an underlying great mind and learning. The brow, while lined with deep furrows is lofty, and his hair, almost iron-gray, sweeps well back from the forehead, while the eye-brows have adopted that quizzical contraction following constant study and deep thought. The eyes themselves are well apart and clear, the cheek-bones setting well up above his beard and lending

them additional intellectual tone. Could

one penetrate the bushy beard which

sweeps down upon his breast, the same

effective strength which characterizes the

rest of his face and personality would

show its lines about his mouth. But John

Muir never shaves, and nature, curbed to

a rough nicety, has not felt the blade of

razor. And to see him and study the contour

of his face would mean to agree that

the cultured and kindly eyes, the fearless

poise of his head and the wrinkles born of long application, would not well permit

of the sacrifice of his beard. It is to

him that "something" which is the distinctive

feature of all great men. Without

it, his appearance would be so altered

as to be almost unrecognizable. He is

strong in mind, body and personality. To

meet him is to be won by his quiet commandery,

and to know him is to be infused

with his strength.

His face must appeal to any student of human nature seeking facial expression, of an underlying great mind and learning. The brow, while lined with deep furrows is lofty, and his hair, almost iron-gray, sweeps well back from the forehead, while the eye-brows have adopted that quizzical contraction following constant study and deep thought. The eyes themselves are well apart and clear, the cheek-bones setting well up above his beard and lending

them additional intellectual tone. Could

one penetrate the bushy beard which

sweeps down upon his breast, the same

effective strength which characterizes the

rest of his face and personality would

show its lines about his mouth. But John

Muir never shaves, and nature, curbed to

a rough nicety, has not felt the blade of

razor. And to see him and study the contour

of his face would mean to agree that

the cultured and kindly eyes, the fearless

poise of his head and the wrinkles born of long application, would not well permit

of the sacrifice of his beard. It is to

him that "something" which is the distinctive

feature of all great men. Without

it, his appearance would be so altered

as to be almost unrecognizable. He is

strong in mind, body and personality. To

meet him is to be won by his quiet commandery,

and to know him is to be infused

with his strength.

John Muir is distinctly of the great West, and not alone that, he is of California,

with the rugged vigor of the

mountain air in bis lungs and the firea of

Southern deserts in his eyes. Give him

the open country or the wooded hill, the

grandeur of the Yellowstone or the barren

wastes of an alkali plain, and in one, as

in the other, he sees only that which is

beautiful, although to any but a lover of

God's own nature there could be no pleasing

significance.

His study represents the work of a lifetime

in contents. Unlike the dens of

many scientists and naturalists, this room

is scrupulously clean, and even the shelves

and cases of minerals, relics of the Indian

age and phenomena of land and sea, are

carefully dusted. In themselves, all of

these things may be considered trivial, but

they reflect John Muir in many ways, and

are typical of the nature of this great and

good man.

In the early morning he is about in

the grounds watching the growth of his

garden and pruning, transplanting or

studying the trees and shrubs. An hour

or more he spends thus, learning the leaves

and flowers, and calling the birds from the

orchard below to flock about his feet. As

an exponent of the simple life, John Muir

is a distinct type. His strength is even

stronger because of its simplicity, and yet

to watch him at his work, few would deem

his duties a pastime. During the remainder

of the day, he may be found in

his den either with microscope as we

came upon him or adding closely written

lines to a voluminous manuscript,

which, dealing with the result of his research,

is shortly to appear in book form.

He works leisurely but steadily, and if he

is fatigued at evening, his face fails to

show it.

It is wonderfully quiet about John

Muir's unique home. There is nothing to

disturb his solitude save the occasional

rumble of a train across the viaduct, and

this, soon losing itself in an echo among

the hills, is the connecting link of the

Primitive and Modern in his life.

At night he scorns the bondage of his

room for a couch on the dormer balcony.

With the weird wail of a skulking coyote

or the screech of a distant owl coming to

him as a call from the great wilderness,

he knows and loves so well, the goodnight

twitter of his feathered friends lulls him

to sleep and rest for the few hours between

darkness and dawn.

Posted 15 May 2019.

Home

| Alphabetical Index

| about this Site &What's New