Note: Hale Tharp, the first non-Native American

settler in what John Muir named the "Giant Forest" in 1875, established

a cattle ranch among the Big Trees. He built a simple summer cabin

from a fallen, fire-hollowed sequoia log in the 1860s. It is the oldest

pioneer cabin remaining in Sequoia National Park. John Muir visited

the area in 1875, and describes meeting a settler there. Although Muir

never identified Hale Tharp by name, from his description it seems

clear that the following vignette describes Hale Tharp quite well.

You can visit "Tharp's

Log" today, on the Crescent Meadow trail in Sequoia National Park.

Resting

awhile ... it

seemed impossible that any other forest picture in the world could rival

it. There lay the grassy, flowery lawn, three fourths of a mile long,

smoothly outspread, basking in mellow autumn light, colored brown and

yellow and purple, streaked with lines of green along the streams, and

ruffled here and there with patches of ledum and scarlet vaccinium. Around

the margin there is first a fringe of azalea and willow bushes, colored

orange yellow, enlivened with vivid dashes of red cornel, as if painted. Resting

awhile ... it

seemed impossible that any other forest picture in the world could rival

it. There lay the grassy, flowery lawn, three fourths of a mile long,

smoothly outspread, basking in mellow autumn light, colored brown and

yellow and purple, streaked with lines of green along the streams, and

ruffled here and there with patches of ledum and scarlet vaccinium. Around

the margin there is first a fringe of azalea and willow bushes, colored

orange yellow, enlivened with vivid dashes of red cornel, as if painted.

Then up spring the mighty walls of verdure three hundred feet high,

the brown fluted pillars so thick and tall and strong they seem fit

to uphold the sky; the dense foliage, swelling forward in rounded bosses

on the upper half, variously shaded and tinted, that of the young trees

dark green, of the old yellowish. An aged lightning-smitten patriarch

standing a little forward beyond the general line with knotty arms

outspread was covered with gray and yellow lichens and surrounded by

a group of saplings whose slender spires seemed to lack not a single

leaf or spray in their wondrous perfection.

Such was the Kaweah meadow

picture that golden afternoon, and as I gazed every color seemed to

deepen and glow as if the progress of the fresh sun-work were visible

from hour to hour, while every tree seemed religious and conscious

of the presence of God.

A free man revels in a scene like this and

time goes by unmeasured. I stood fixed in silent wonder or sauntered

about shifting my points of view, studying the physiognomy of separate

trees, and going out to the different color patches to see how they

were put on and what they were made of, giving free expression to my

joy, exulting in Nature's wild immortal vigor and beauty, never dreaming

any other human being was near.

Suddenly the spell was broken by dull

bumping, thudding sounds, and a man and horse came in sight at the

farther end of the meadow, where they seemed sadly out of place. A

good big bear or mastodon or megatherium would have been more in keeping

with the old mammoth forest. Nevertheless, it is always pleasant to meet

one of our own species after solitary rambles, and I stepped out where

I could be seen and shouted, when the rider reined in his galloping mustang

and waited my approach. He seemed too much surprised to speak until,

laughing in his puzzled face, I said I was glad to meet a fellow mountaineer

in so lonely a place. Then he abruptly asked, "What are you doing?

How did you get here?" I explained that I came across the cañons

from Yosemite and was only looking at the trees. "Oh then, I know," he

said, greatly to my surprise, "you must be John Muir."

He was

herding a band of horses that had been driven up a rough trail from the

lowlands to feed on these forest meadows. A few handfuls of crumb detritus

was all that was left in my bread sack, so I told him that I was nearly

out of provision and asked whether he could spare me a little flour. "Oh

yes, of course you can have anything I've got," he said. "Just

take my track and it will lead you to my camp in a big hollow log on

the side of a meadow two or three miles from here. I must ride after

some strayed horses, but I'll be back before night; in the mean time

make yourself at home."

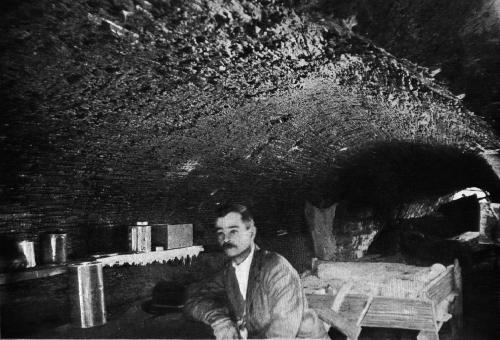

He galloped away to the northward, I returned

to my own camp, saddled Brownie, and by the middle of the afternoon discovered

his noble den in a fallen Sequoia hollowed by fire-a spacious loghouse

of one log, carbon-lined, centuries old yet sweet and fresh, weather

proof, earthquake proof, likely to outlast the most durable stone castle,

and commanding views of garden and grove grander far than the richest

king ever enjoyed. Brownie found plenty of grass and I found bread, which

I ate with views from the big round, ever-open door. Soon the good Samaritan

mountaineer came in, and I enjoyed a famous rest listening to his observations

on trees, animals, adventures, etc., while he was busily preparing supper.

In answer to inquiries concerning the distribution of the Big Trees he

gave a good deal of particular information of the forest we were in,

and he had heard that the species extended a long way south, he knew

not now far.

I wandered about for several days within a radius of six

or seven miles of the camp, surveying boundaries, measuring trees, and

climbing the highest points for general views. From the south side of

the divide I saw telling ranks of Sequoia-crowned headlands stretching

far into the hazy distance, and plunging vaguely down into profound cañon

depths foreshadowing weeks of good work. I had now been out on the trip

more than a month, and I began to fear my studies would be interrupted

by snow, for winter was drawing nigh. "Where there isn't a way make

a way," is easily said when no way at the time is needed, but to

the Sierra explorer with a mule traveling across the cañon lines

of drainage the brave old phrase becomes heavy with meaning. There are

ways across the Sierra graded by glaciers, well marked, and followed

by men and beasts and birds, and one of them even by locomotives; but

none natural or artificial along the range, and the explorer who would

thus travel at right angles to the glacial ways must traverse cañons

and ridges extending side by side in endless succession, roughened by

side gorges and gulches and stubborn chaparral, and defended by innumerable

sheer-fronted precipices....

Bidding good-by to the kind Sequoia cave-dweller, we vanished again

in the wilderness, drifting slowly southward, Sequoias on every ridge-top

beckoning and pointing the way. |