sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - july/august 2012 - memories of a conservation giant: david brower at 100

David Brower at 100

By John de Graaf

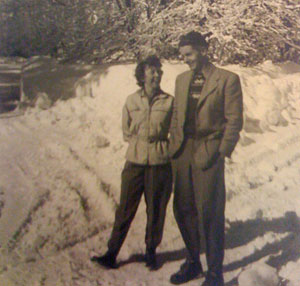

David Brower with wife, Anne Brower.

David Brower with wife, Anne Brower.

Anne was the real rock of David's life, putting up with his nights at the office and long lobbying trips away from home.

She was not always happy about it, as one letter in his University of California Bancroft Library archive reveals, hinting at divorce if the absences continued. But Anne knew that marriage to a hero is the hardest kind, and she handled it with her characteristic dry humor. "When David got that job as executive director of the Sierra Club," she once told me, "I thought, well, now that he's working full-time for the Club, he won't want to spend his evenings and weekends in the office. But I was quite mistaken."

Brower barely knew Anne when he proposed marriage to her, in a letter while he was away in the Army. "And since I had never even kissed him, it seemed a bit abrupt," she recalled with a smile. But she agreed; their first date came after they were married. Yet the marriage lasted till Brower died nearly 60 years later. David's sense of humor was no less acute than Anne's; he frequently asked listeners the question "What do environmentalists and the Bible have in common?" The answer: "No humor."

Over the years, I've gotten to know two of Brower's four children, his oldest son, Ken, and daughter, Barbara. Both have inherited the ideals and quick wit of their parents. Barbara is a professor of Himalayan geography, Ken an author of books and of articles for many publications, including National Geographic. His newest book, The Wildness Within, is a collection of interviews with many of the people who knew his dad best.

BROWER'S POLITICS

Brower's wit often had political implications. In the mid-1990s, when Newt Gingrich was Speaker of the House, Brower took me to Tilden Park in Berkeley and showed me signs on the park road with a picture of a salamander and the warning "NEWT CROSSING" on them. The signs were there to slow motorists during the tiny amphibians' mating season, when many crossed the road in search of conjugal connections. "Those are the newts I like," Brower said with a grin.

Brower built bridges to organized labor, helping start the Blue-Green Alliance with United Steelworkers union leader David Foster. He called out fellow environmentalists for their inattention to racism and class injustices, and he hallenged a bloated military and its unnecessary wars. But though he is often cited for being a Jeremiah, unwilling to compromise, he was no hard-boiled ideologue. He frequently complained that progressives had failed to thank Richard Nixon for the EPA, the Endangered Species Act, and other pro-environmental legislation. One must not only criticize, he was quick to say.

"We don't propose compromises; we let the politicians make the compromises," he once declared. But the flip side to that included an appreciation of the compromises even the best political leaders are sometimes compelled to make.

Brower's ideas changed with better information. Once a fan of nuclear power, he became an implacable foe when he realized the dangers it presented. A Republican in his younger days, he turned Democrat, and then mostly Green.

SOCIAL RETICENT

For all his leadership skills, Brower was essentially a shy man, a trait captured perfectly in John McPhee's Encounters With the Archdruid, a tale of David's interactions with "three of his natural enemies." I was also struck by his shyness. "I'm more comfortable speaking to a thousand people than one-on-one with a stranger," he told me. He needed libation to loosen up--a Tanqueray martini being his favorite. I discovered that people who met Brower in formal settings when he hadn't had his martini often found him cold and aloof. But it was social reticence, not hubris. Anyone who'd closed a bar with him remarked about his warmth, and especially about how he asked questions and listened to the answers. He was unusually effective at drawing out young people in this way, and many, after their first encounter with him, signed on to volunteer. He made good use of their skills; when teacher Mark Terry mentioned at a conference that he wished there was a handbook for environmental education, Brower tapped Terry to write it and found him a publisher.

For more than a few young people, the opportunity to get to know Brower came during regular Sunday-morning waffle breakfasts at his home. Dave, as everyone called him, made delicious Belgian waffles, moist from a batter that included shredded fruits and vegetables. The breakfasts were a form of Sunday church for Brower. He wasn't religious, but rather, spiritual. His religion, Ken Brower says, was wildness, the environment, the mountain peaks that were cathedrals to his hero, John Muir.

He was a generous man, and I was often the recipient of that kindness, especially in 1986, when I phoned him at home in Berkeley. I'd tried to make a film about him in 1981, and we'd done some shooting, but as an inexperienced producer then, I couldn't find the funds to complete the documentary, and it fell by the wayside. Five years later, with other PBS productions under my belt, I was encouraged by a friend, Carolyn Gates, to try again. I called Brower with some trepidation, wondering if he'd already written me off as a flake. "I don't know if you remember me, but . . ." I started cautiously when he answered.

1 | 2 | 3 | next >>