|

|

Grow up, go wild, get married, settle down: However you change, the mountains will welcome you home.

by Daniel Duane

I first saw the country east of Mt. Conness in 1983, when my father decided that his snotty teenage son needed a healthy Sierra weekend. Pop admitted that camping couldn’t possibly be as much fun as my ultracool social life in Berkeley, and he didn’t think there would be any video arcades, either. But what if we tried a mountain climb? Against my better judgment, I let the old man–droopy mustache, wide leather belt–wake me up too early and buy me coffee and drive me clear across the Central Valley. Rattling along in his VW bus, I talked the whole way about my dynamite bulimic girlfriend and also my worry that I didn’t have the talent to be a rock star, which was devastating, but something I really wanted to confront. After five hours and 9,000 feet of elevation gain, Pop turned off the highway near the Tioga Pass Resort, a log-cabin lodge and restaurant. The Saddlebag Lake Road, a dirt track in a U-shaped valley, led into a quiet glacial drainage. Where that drainage swung left, away from the road and into the higher mountains, Pop stopped at the Sawmill walk-in campground. I first saw the country east of Mt. Conness in 1983, when my father decided that his snotty teenage son needed a healthy Sierra weekend. Pop admitted that camping couldn’t possibly be as much fun as my ultracool social life in Berkeley, and he didn’t think there would be any video arcades, either. But what if we tried a mountain climb? Against my better judgment, I let the old man–droopy mustache, wide leather belt–wake me up too early and buy me coffee and drive me clear across the Central Valley. Rattling along in his VW bus, I talked the whole way about my dynamite bulimic girlfriend and also my worry that I didn’t have the talent to be a rock star, which was devastating, but something I really wanted to confront. After five hours and 9,000 feet of elevation gain, Pop turned off the highway near the Tioga Pass Resort, a log-cabin lodge and restaurant. The Saddlebag Lake Road, a dirt track in a U-shaped valley, led into a quiet glacial drainage. Where that drainage swung left, away from the road and into the higher mountains, Pop stopped at the Sawmill walk-in campground.

He had heavy leather boots in those days, and I watched them lead the way through the dozen campsites, with the picnic tables and the stunning views. Then we crossed a wide and shallow creek, water gurgling over the rust-colored cobblestones and wiggling the low-slung willows.

A gentle climb took us into the perfect little rock-garden meadows, with their wildflowers and murmuring brooks, powder-white boulders and bonsai-like pines. Higher still, while I asked my father if I should cut my long hair and join the preppy crowd, the meadows ran into an ice-blue lake backed by giant rocky slopes. My father, who was in great shape, had picked out a big goal: the 12,500-foot summit of Mt. Conness. Oblivious to the effects of altitude, we started up a steep talus field. My heart was pounding by then, and I stopped talking. After at least an hour of hard work, we found a narrow notch through a ridge, and clambered over coarse boulders in the solitude of the sky. It was easily the wildest thing I’d ever done, and we emerged onto a high plateau of bare stone and windy silence.

I don’t recall the summit, which suggests we never got there, but I do recall the way down. Having gone from sea level to perhaps 11,000 feet in a single day without sunglasses, a hat, water, or much of a lunch, I succumbed to cranky, headachy nausea. In response, my contrite father drove right to the Tioga Pass Resort, where I passed out while puking on the concrete floor of the men’s room. I remember also that a first bowl of chili settled my stomach, a second brought a smile to my face, a first cheeseburger helped me admit that I’d just had the coolest adventure of my life, a second cheeseburger had me wondering if I might even have a natural aptitude for mountaineering. A first slice of apple pie à la mode set my father to laughing and double-checking his wallet, and a second slice of apple pie à la mode ushered me into a blissful sleep.

Eight years later, having gone whole hog–Toyota pickup, mountain shop retail job, the certainty that I was born to rock climb–I’d staked a personal claim to the country east of Conness. Working only part-time in Berkeley, I spent whole weeks pushing my (relatively modest) limits up there, accompanied by a New Zealander on a round-the-world tour. At the end of yet another fantastic route, feeling like liberated heroes, we’d heat beans and tortillas, open a jar of salsa, and drink beers in the setting sun–maybe even take out the guitar and play some Neil Young (my having resigned myself to amusing friends and relatives). With our hands bloodied from the rock and our muscles sore, we’d giddily pick out an even bigger and harder climb for the following day–ever onward and upward. Then we’d scoot out the Saddlebag Road, turn off at Sawmill, and, because we had no use for a campsite, slip into the forest to sleep.

The morning sun comes awfully late to Sawmill–although it shines on the meadow across the creek–and we were always in a big hurry. Instead of lingering, waiting for the day, we’d jump out of bed and stuff our sleeping bags and hurry down to what we now called TPR, Tioga Pass Resort. Beating the breakfast rush took some doing at that place, because they employed a dream team of pretty waitresses, all of whom were excellent rock climbers: the raven-haired Mexican-American beauty named Dorie, who climbed in cutoff Levis and a lacy white blouse; the Scots-Irish Mary, whose bawdy laugh said she could out-drink, out-climb, and out-romance any of us; Brynn, a vulnerable and petite blond with downy cheeks and rock-hardened hands; and Vedra, the lovely and bookish brunette. Climbing at Tuolumne Meadows was in a renaissance that summer, with every hot American climber competing for a place in the future guidebooks. Dorie was dating the movie-star-handsome Ron Kauk, crown prince of California climbing, and Vedra was entangled with a 19-year-old poster boy. I couldn’t climb at that level, but I was working on it, and I did bring the girls the odd pound of gourmet coffee beans from Berkeley. When I finished my pancakes, they’d even refill my cup from the private staff pot.

I thought I was building something–honing skills, doing what I loved–and by mid-August, the Kiwi and I were tackling our hardest routes early so we could climb with the TPR girls when they got off work. Once, after Dorie and Kauk broke up, Dorie caught sight of him in the forest and insisted we flee the area–just avoiding that guy felt to me like a social coup. Best of all, at least in memory, were the long afternoons with Vedra. On one pyramid-shaped mountain, where a Frenchman had recently died, we moved fast in a calm blue sky, both of us so well adapted to the stone and the ropes that our minds were free to savor the crazy joy of being alive. We lay on the tiny summit for hours, talking about everything and nothing, and I couldn’t help wondering what she saw in her skinny boyfriend, why she wouldn’t prefer a nice guy like me.

The Kiwi and I were also working toward a particular big wall, and when we’d finally done it–a consummate achievement–we kidded ourselves with the idea that, as climbers, we were just getting started. Within days, we had a new tick-list, including a big face on Mt. Conness. The Conness approach, as it turned out, followed the same hike I’d done with my father all those years ago. I certainly knew the way: past the campsites, across the shallow creek, along the rock-garden meadows and up the talus field. Remembering my father’s lead, I took us right through that notch to the high plateau. But when the Kiwi and I caught sight of the climb itself, it looked exhausting and beside the point, and we discovered we’d run out of ambition. Perhaps in doing our big wall, perhaps just in having such a fun summer, we’d both lived out whatever drama had brought us there in the first place. Neither of us knew this, of course, but we laughed out loud and chose the easy way up, leaving the ropes in our packs and walking to the very summit I had not reached with my father.

This time I’d brought plenty of food and water, and I was well acclimated, so the hike down was a pleasure and I could actually notice things–exquisite little lakes and red and yellow wildflowers highlighting the meadows. We even savored dinner in a proper Sawmill campsite–nice views, no cars, very few people. The next morning, the Kiwi boarded a bus to the airport and I napped in the shade, peaceful and sad–sensing, I think, that a wonderful moment was passing. I found Vedra and she told me that the TPR season was almost over; she’d have to find a winter job and she was thinking about the Rockies. My heart lifted when she said her boyfriend had deserted her for the widow of the dead Frenchman. But then, revealing that she saw me as a confidant and not a prospect, Vedra added, "I just can’t imagine what a 30-year-old French lady can do for him that I can’t." Spurned and hurt, I thought, Really?

We all know we can’t freeze happiness, but it’s hard not to try, or to wish it weren’t so. Life took me elsewhere, for a while, to graduate school and teaching, and I saw the country east of Conness no more than once or twice a year–weekending with my father or with my old college roommate. I’d always have a good time, but I was bothered by the feeling that I no longer knew who I was up there. My skills were fading, and while I loved the climbs I could still do, I had to wonder why I’d worked so hard and made all those friends only to walk away. Waking up early at Sawmill, seeing the frost on the flowers and the dawn amber on the white rock of Conness, I always made a point of breakfast at TPR, and while Vedra never worked there again–she married a lucky cabinetmaker in Colorado or somewhere–Mary and Dorie remembered me. "Hey, how long you around for?" Mary always asked, being polite. Then she’d catch me up on the latest routes and which famous climber passed through yesterday. Mary also told me that the climbing world had moved on to steeper cliffs: "Notice how empty everything is?" I tried to take comfort from the notion that I’d been there while the getting was good, or that the world I’d left no longer existed. Of course, the blue mountain sky still rang bright and the granite felt as hard and pure as ever. One year, I heard that Dorie had suffered complications in a routine knee surgery, and although in truth I’d barely known her, the news felt like a personal blow. The next summer, she still looked gorgeous, but I caught a worried pain in her eyes. She’d relocated to San Jose and was going to college, and I thought, Right, everybody’s got to move on.

Eventually, I let a whole summer go by without a single trip. I had an excuse, of course: I’d fallen head over heels in love, and my August adventure involved a dozen roses, my grandmother’s diamond ring, and a rooftop marriage proposal. Liz, a writer like me, had spent a summer as a Colorado park ranger and she loved the mountains as much as anybody, but she also grew up back East, so we spent our vacation that year on courtesy calls to my soon-to-be in-laws. We enjoyed it all, but the absence, the failure to make a seasonal trip to Yosemite’s high country, felt awful, a step too far. That, I thought, must never happen again, and luckily my college roommate, like a good best man, suggested we get away before the wedding. We’d camp at Sawmill, of course, but leave the rope and bring a double-burner stove and a cooler instead. And it wasn’t so bad: We got a great campsite, we grilled meat and drank beers, we talked about the Big Issues. On my last unmarried morning, we found a pool in the creek. Slipping into the ice-cold water, making up some goofiness about ritual cleansing, or binding the past life to the future, I felt a vague ache and also a new kind of gratitude. Something like, Boy it sure is great just to be here, if only for a day.

One thing I’ve always loved about the mountains is the way you hear the wind before it reaches you. Waiting in the stillness, you hear the build and rush as it grows closer, and then it’s upon you and the pine boughs swing. On my first Sawmill morning with Liz–thrilled to show her everything–we lingered happily with our tent door open, huddling against the down-mountain breeze. She was utterly dazzled, confirming our shared sense of what matters. At 8:30, when the sun still hadn’t found our site, I suggested the next step in my usual Sawmill approach: "How about a little French toast, down at TPR?" But Liz doesn’t go to the mountains to eat in restaurants, and she likes to find her own relationship to a place. So she said, "Well, what if we took coffee across that creek instead? To where the sun’s already shining on that meadow?" Ah . . . well, what a wonderful idea. What a brilliant and obvious idea. "In fact," she said, "why don’t we bring cereal, too, and some fruit? And our ground pads? And books?" Several hours later, in a completely novel approach for me, we’d lost the morning in the suggestive voice of the stream. It takes very little to entertain the two of us, and the afternoon fell in a similar way: Liz looked up the south slope of the valley and asked if I’d ever hiked it. Well, gee, no. Not really. I was too busy rock climbing all those years. And, once again, Liz showed me a new face to the place I thought I knew. The open ground of the Sierra encourages a freedom of movement–pick a new direction and wander off, see where you end up. Liz led the way to a clear blue lake, without a soul around, and we shuttled from hot granite slabs to the frigid thrill of a snowmelt swim. We did the same thing the next summer, with Liz eight months pregnant and happy to call Sawmill her own–crossing the creek for a breakfast picnic, swimming in the same cold water, dozing among the Indian paintbrush and watching an iridescent insect agleam in the light.

This spring, when Liz and I sat with baby Hannah on our living room floor, I noticed that my Conness fantasy had taken a completely new shape: Got to get the little family up to Sawmill, take a dip in our lake, let the baby play in our favorite meadow. As it happened, I ended up going first alone–in early June, when work took me to Bishop and a canceled meeting left a free day. The Saddlebag Road was still closed for winter and snow lay in leopard-skin patches on the mountainsides, so I parked the truck and set out on foot. I wanted to walk out the road and through the campground, see all the places that Liz and I enjoyed, but the creek ran so high and strong that I worried I wouldn’t be able to cross up above. There was a bridge right there, so I used it to reach a trail on the opposite side of the creek. From the first step, my next education began: Springtime at 10,000 feet meant so much snow melting so fast that entire slopes trickled and bubbled. Fields of fresh water made temporary creeks a hundred feet wide and an inch deep. Pocket lakes drowned what would soon be pocket meadows and the bare ground lay gray-brown in the warm sun. Chipmunks scurried and the willow branches showed only the smallest of leaf buds, little flecks of green.

I’d forgotten to bring boots, so it was slow going, trying to keep my feet dry. I did a lot of picking and poking, threading along the dry patches. Summer, I realized, masquerades as a moment of stasis, a fixed state of being. Year after year, at the same season, the meadow sparkles and the birds chirp; day after perfect day, there’s a seemingly stable relationship of shrub to forest, flower to water. In spring, on the other hand, the mountains molt their frozen skin without a living skin to replace it. There’s a contingent quality to everything you see: Last year’s dead pine needles lying atop the mulched-in needles of the year before and even the creeks seeming less like distinct things than fleeting inevitabilities, a little low ground and the way water can only run over it; this week’s inch-deep pond of snowmelt is next week’s patch of grass.

It was a reminder of what I’d already known about freezing happiness. Hard not to feel the heart tug, of course, with Liz and Hannah back at home while I stood alone in a valley I’d first seen with my father, but for a moment I managed to hold it all in my mind: stumbling downward as a teenager; reaching the summit of Conness with my Kiwi friend; the pre-wedding bath with my college roommate; and now Liz’s marvelous rewriting of my mental Sawmill map, the way she’s given my favorite place back to me by claiming it for herself. And maybe that’s the best way to say this, the best way to articulate the gift of a single mountain cirque, of your familiar campsite and that shallow creek and the sunny meadow full of flowers: It’s not just a world that stays the same while you change, but a world that keeps changing in more or less the same way, relentlessly, so you can believe that your own changes will work out fine.

Daniel Duane is author of several books, including Lighting Out: A Vision of California and the Mountains (Graywolf Press, 1994), Caught Inside: A Surfer’s Year on the California Coast (North Point Press, 1997), and a novel, A Mouth Like Yours, forthcoming from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Wild California is just a Sierra Club trip away. Go to www.sierraclub.org/outings/national, or contact Sierra Club Outings, 85 Second St., 2nd Floor, San Francisco, CA 94105; (415) 977-5522.

Tomorrow’s Wilderness

Here are a few of the 87 areas embraced by the California Wild Heritage Act, the first statewide wilderness bill for California since 1984. The legislation, introduced in the Senate by Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) and in the House as two companion bills by California Democratic representatives Hilda Solis and Mike Thompson, would protect 2.7 million acres of wilderness and wild rivers in the state.

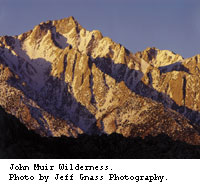

The grand vistas of the eastern Sierra would be protected by expanding John Muir Wilderness (below), where trout-bearing streams and bighorn sheep habitat are threatened by off-road-vehicle routes, mining, and resort development.

California’s "Lost Coast" will remain blessedly lost if 41,000 acres of the King Range, including the longest stretch of undeveloped coastline in the United States outside Alaska, are protected as wilderness. Here, hikers can walk 24 miles of rugged beach or traverse rare ancient forests of Douglas fir, madrone, incense cedar, and tan oak.

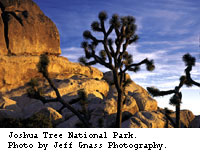

A million visitors a year come to admire Joshua Tree National Park’s rock formations, spring wildflower displays, and its Old Testament–evoking trees. The California Wild Heritage Act would expand the park’s wilderness by more than 36,000 acres, including Lost Horse Valley (above), one of the most popular hiking areas. A million visitors a year come to admire Joshua Tree National Park’s rock formations, spring wildflower displays, and its Old Testament–evoking trees. The California Wild Heritage Act would expand the park’s wilderness by more than 36,000 acres, including Lost Horse Valley (above), one of the most popular hiking areas.

Geysers, lakes, ancient forests, verdant meadows, and even half of 10,457-foot-high Lassen Peak itself are not yet protected as wilderness at Lassen National Park in Northern California. The designation would protect sensitive habitat for California spotted owl, goshawk, pine marten, fisher, bald eagle, Sierra Nevada red fox, and other species.

The rugged canyon of the Middle Fork Feather River would be protected in the Feather Falls Wilderness. Boasting the sixth-highest waterfall in the United States, the remote gorge serves as a corridor for wildlife moving from the Sierra foothills to the Great Basin. The rugged canyon of the Middle Fork Feather River would be protected in the Feather Falls Wilderness. Boasting the sixth-highest waterfall in the United States, the remote gorge serves as a corridor for wildlife moving from the Sierra foothills to the Great Basin.

Head east of the soaring Sierra and you encounter the daunting White Mountains, home to bristlecone pines, the longest-living plants in the world. Nearly 300,000 acres of these rugged mountains could become wilderness. In the Whites, a hiker can move from desert alkali shrubs through piñon-juniper woodlands onto alpine barrens, the ecological equivalent of walking from the Mojave to the Arctic.

|