sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - november/december 2009 - winter tracks

Winter Tracks

Seeking a guilt-free winter break, with snowboard and train ticket

By Peter Frick-Wright. Photography by Heath Korvola

Whitefish local Brad Lamson nears the top of the group's first climb, with the peaks of Glacier National Park behind.

Breezing through the big wooden doors of Union Station in Portland, Oregon, I take my time getting to the ticket counter.

"How late is it?" I ask the clerk.

"How late is what?" she replies.

"Amtrak," I say.

"Late? It's about to leave!"

Please excuse my assumption. Amtrak's reputation precedes it. All I heard in the weeks leading up to my effort to take a low-carbon, train-based snowboarding trip were horror stories of Amtrak runs delayed as freight and errant tumbleweed took priority. In his new book, Waiting on a Train, journalist (and high-speed-rail fan) James McCommons writes, "Veteran riders of Amtrak's long-distance trains just assume the train will be late. And they try to stay patient."

The cynic in me says that trains are too unreliable for Americans to take to the rails, yet here I am running down the platform, my wheeled snowboard case wobbling. The load topples, pulling me like a stubborn donkey. The conductor seems to be enjoying this. He might be holding the train just to watch.

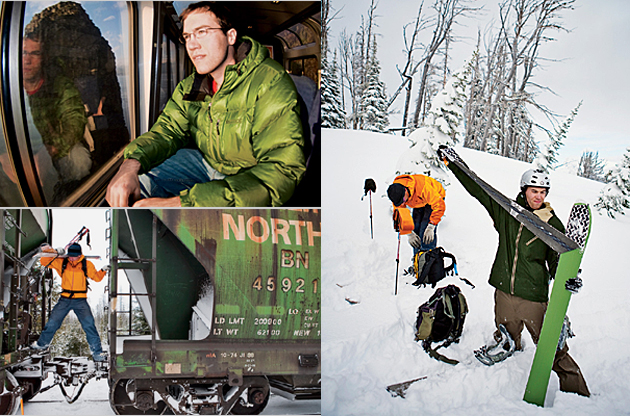

Clockwise from top left: The author aboard Amtrak's Empire Builder; removing climbing skins from a splitboard; taking a frowned-upon shortcut to the trails.

Like so many winter adventurers, I struggle with the hypocrisy of enjoying remote mountain destinations while pumping out climate-warming carbon dioxide to get to them. Small changes in climate, it turns out, have a big impact on winter destinations. A 2008 study by geographer Mark Williams, a fellow at the University of Colorado's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, found that Colorado's Aspen and Utah's Park City resorts should expect delayed snowpack and shorter ski seasons by 2030 even if the world begins reducing its carbon dioxide emissions. If CO2 emissions increase, Williams anticipates, Park City will have no snowpack at its base by 2100. Scientists' modeling predicts that Glacier National Park's retreating icefields will have vanished by 2030.

I want to see whether I can ride the rails to a near-zero-emissions vacation. I'm shunning cars and even resorts, with their electricity-gobbling chairlifts. (Alas, even trains create a carbon footprint, bigger than it might appear.) I've brought a splitboard, a two-piece snowboard that allows riders to ascend backcountry slopes like cross-country skiers. In short, I want to see whether I can ski without contributing to the demise of skiing.

From Portland, Amtrak's Empire Builder cuts across southeast Washington and Idaho to Montana's Flathead Mountains, near Glacier, in 16 hours. In the Flatheads, the wet, heavy snow of the Pacific Northwest gives way to dry, light powder, and Canada's mountains (usually) moderate the subzero arctic air streaming south to a crisp and comfortable 20 degrees Fahrenheit. There may be no better place to pursue fresh tracks.

Montanan Pete Costain floats through northern Rockies fluff. The next day he will make willing truants of his snow-loving kids.

Montanan Pete Costain floats through northern Rockies fluff. The next day he will make willing truants of his snow-loving kids.

"We could have skied out the front door today," my guide, Mark Ambre, says,"but it would have been a wet slog, and we might have died." We're on our way to Essex, Montana's Izaak Walton Inn after a day of skiing through a forest-fire burn on Divide Mountain, talking over the road noise of a minivan. My automobile-eschewing ambitions lasted one day.

From the driver's seat, Ambre points out avalanche danger spots that a night of rain had created in the top-heavy snowpack, forcing us to drive 70 miles around the park to its dry eastern side.

Our climb up Divide Mountain had taken us through ghostly lodgepole and aspen--blackened by fire or bleached white by the sun--to an overlook, where we donned our gear. The snow was light and fast, and we picked up speed until the trees blurred into a fuzzy rhythm of black and white. Slicing through the dry snow, we slalomed among the trees and into a small drainage. As we carved back and forth, tufts of snow shot out behind us.

A backcountry ski guide who has never owned a car, Ambre is supposed to be my authority on emission-less travel, a kind of sensei to my grasshopper. He travels exclusively by bike and train during the summer and skis all winter. In addition to the environmental benefits, he says, it's almost a game, like when rock climbers ignore easy holds to make a route more fun. He's made a lifestyle out of my vacation challenge.

But everyone has skeletons. "I say I've never owned a car," he says, "but I've probably driven more than most people." As a teenager, he took a job delivering cars cross-country. He'd start a 10-day journey from Washington, D.C., to Seattle by disconnecting the odometer and inviting some friends along for a 4-day backpacking trip. Then maybe he'd detour through New Mexico, head north to Lake Tahoe, and end with an all-night sprint to Seattle as time ran out.

No pain, no pure powder pleasure: Pete Costain climbs a 7,200-foot peak.

These days Ambre drives the lodge's minivan only when a client pays him to, and those trips serve a larger purpose. "You have to get people outside and take them to these places because then they'll show up and fight for them," he says.

It's a maxim he lives by, guiding skiers out of the Izaak Walton Inn, a chalet within a snowball's throw of the train tracks. Originally housing for railroad workers, it now caters to skiers and railroad enthusiasts perfectly happy to spend a day chatting about passing trains. A sign asks guests to preserve the ambience by refraining from using their computers in the lobby or restaurant.

The place is decorated with railroad memorabilia and Rocky, a scarf-wearing mountain goat mounted on the wall. Essex has a population of 35. You can tell the locals because most anyone who lives here works at the hotel.

There are no phones in the rooms or locks on the doors or TVs anywhere. Cell phones don't work. It's wonderful, and probably an effective punishment for certain types of plugged-in teenagers.

At night, guests sit next to the fire reading or talking to complete strangers. This can be a little disconcerting if you're not ready for it.

"You're the guy with the funny skis outside?"

I'm standing in the lobby, near the door, directly beneath Rocky's stuffed head, as a gallery of curious faces look up from books and magazines, turn away from the fire and toward the next guest speaker: me.

"It's a splitboard," I say. "You hike up the mountain on skis, then it fastens together to become a snowboard on the way down."

"Really?" one onlooker says. "How does it work?"

And so I find myself giving an impromptu clinic on the merits of backcountry boarding to a room of rail fans. I explain how skins attach to the underside of the board and allow it to glide forward without slipping back, and how, yes, formerly animal skins were used but these are nylon. Riding the backcountry makes every run a descent through buttery-smooth, untouched powder, I say.

I'm not a complete gearhead, but it turns out that when you're not in the snow, the next best thing is talking about the equipment that takes you there. I'm just hitting my stride when the front desk announces that my train is waiting.

Whitefish, Montana, is a railroad-and-ski town an hour's ride west of Essex--and the busiest Amtrak stop between Seattle and Chicago, with 60,000 visits per year. Its downhill ski area, Whitefish Mountain Resort, looms four miles north of town. That name is recent; the locals still call it Big Mountain.

Any Whitefish restaurant worth its chili has posted a sign, taken from a chairlift, that reads, "Please check for loose clothing and equipment and prepare to unload." Whitefish has about 7,000 people; here you can tell the locals because they wear leather work gloves instead of ski gloves.

I've arranged to ski with several of those locals, cold-calling them after searching "Whitefish" and "backcountry ski" on the Internet and asking whether they'll take me into the mountains. It turns out that there's a group of mostly retired gentlemen who meet every Wednesday at 10 a.m. at the top of Big Mountain for a day of backcountry skiing like you or I might meet for coffee. Ben Stormes, a relocated businessman who now guides and teaches avalanche-safety classes for outfitter Whitefish Backcountry ("My wife calls it a midlife-crisis job"), has arranged for me to join the group. The single chairlift ride is against my principles, but I figure that with Amtrak under my belt, I've earned some carbon-dioxide-emissions credits.

A former ski patroller with a rugged scar on his nose from skin cancer, Stormes is fond of dirty jokes and seems to know everyone. We meet Peter Aronsson and Kim Richards at the top and discuss the avalanche danger that has thinned out their group today. It's snowing hard, there's an unstable layer under the surface, and Stormes forgot his helmet. We go anyway.

After one run, we stop in a wind-protected clearing on the north side of the slope. Two skiers' tracks run down directly to our left, with nothing but a thick sheet of open snow below.

Stormes digs a test pit to check the stability of the snow layers beneath us, and he and Aronsson start talking about growing up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. It turns out that they used to live a few blocks from each other, though they are decades apart and never met there.

Stormes gets results from his tests ("I like what I'm seeing!"), and Richards records the data in a notebook. Aronsson is reliving his Grosse Pointe days. "My house was on the former property of the man who owned the patent on the automobile," he says. "He didn't have to work."

Stormes starts his run, carving behind a tree. We hear the quiet rumble of moving snow as it hits him from behind, taking his skis out from under him. Stormes tumbles several times, losing one ski, then the other. He's alone in the "white room" of an avalanche and takes a mouthful of snow. He goes headfirst into a tree, then stops. From up top, I can see the slide but not Stormes.

Fortunately, Stormes can move. A leg. A shoulder. Both shoulders. He hears Richards calling and answers.

As we hike out through a valley where a skier was killed by a slide the previous year, Stormes keeps going over the mistakes that led to the slide. He was too eager to drop in, and someone else had safely gone before him. "I teach this stuff," he keeps saying.

We go to dinner, and he brings his sons, telling me how he left a high-stress job to become a ski bum. "I think moving here is going to add 10 years to my life," he says with no apparent irony.

The next morning, Whitefish photographer Heath Korvola picks me up very early at my hotel. He's recruited a couple of local skiers, Brad Lamson and Pete Costain, to join us. We pile into Korvola's Subaru and head away from the unstable snowpack that slid yesterday.

Again, a car. This may be the major flaw in my plan for a carbon-neutral winter adventure: While a downhill skier at a lift-served resort can probably get by without a vehicle, great backcountry spots are rarely found along bus routes. Sharing a ride is the best we can do.

It's six degrees, and my nostrils freeze with every breath as we glide through two feet of what Ted Steiner, the railroad's avalanche guru, said was the lightest snow of the year. We stop when we find an idling freight train blocking our path. We climb between two cars, clicking back into our skis on the other side.

As soon as the Whitefish boys see open trail, they disappear up the mountain. I'm in shape, but Lamson runs ultramarathons, and Costain climbs Big Mountain for fun. I'm also sliding backward with every other step, my wide snowboard halves slipping out of the narrow ski tracks they put down. After a half hour, they stop waiting for me. A half hour after that, I slide into a tree well and get stuck.

I will condense the misery for you: I would rather have been mounted on the wall next to Rocky.

When I crest the climb three hours later, though, all suffering is forgotten. I swerve among buried treetops, the slightest course correction sending up a spray of powder. Even with snow above my knees, the board drifts through turns without the faintest susurrus. At the bottom, I'm salivating for another run, the urge to ride as intense as a teenage crush. Tomorrow, Costain will pull his kids out of school so they can ski this snow.

When we reach our final summit, we have little time to savor the upcoming run or take in the 360-degree view of Glacier's cathedral-spire peaks. We're losing daylight, and we still have a six-mile ski back to the nearest road. Dropping into our last set of turns, we pop through the bouncy snow, sending out feathery rooster tails behind us. Lamson calls it "3,000 feet of pure joy."

The Whitefish boys all have families, so I head back to my hotel to crash. These last two days I've ridden the best snow of my life, dodged avalanches, and climbed a mountain--and all I'm missing is someone to share my stories with.

As I board the Empire Builder homeward the next night, the conductor takes a long look at my oversize snowboard bag and makes room for me on the lower level so I can sit with it. It's then that I begin to understand why people take the train, despite the potential for delays.

The car is packed, and several passengers watch me wrestle the bag into place. As I stretch my legs out on the soft case, one asks, "What's in that bag?"

Curious onlookers look up from books and magazines and lean in.

"It's a splitboard," I say, straightening up a bit to deliver my speech. "It lets me hike up the mountain on skis and becomes a snowboard on the way down."

"Really?" she says. "How does it work?"

Peter Frick-Wright, a frequent contributor to Sierra, last wrote about cycling Mt. Hood ("Because It Hurts," March/April).

See other images from the trip on photographer Heath Korvola's blog.

Photos by Heath Korvola; author photo courtesy of Peter Frick-Wright.