sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - january/february 2010 - mixed media

Mixed Media | Deep Thoughts and Oddball Interpretations

Think Like an Eco-Baron | Crash-Test Panda

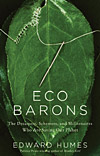

Think Like an Eco-Baron

Who Needs Old Money When You've Got New Ideas?

Author Edward Humes reimagining the role of Monopoly's Rich Uncle Pennybags.

Author Edward Humes reimagining the role of Monopoly's Rich Uncle Pennybags.

Not long ago there was a computer plant in Asia spinning out two lines of laptops, one bound for Europe and the other for a retail chain in the United States. The European laptops had been stripped of toxics, per European Union regulations; the laptops bound for the United States, where industry had long fought such regulations, were far less green but otherwise identical. The cost to produce them: the same.

When a sustainability consultant showed the retail chain's buyer this triumph of stupidity, the buyer wondered why he couldn't have the green laptops too. "Because you never asked," the factory manager said. So the buyer asked. And because the manufacturer was able to merge the two lines, going green dropped the price of the laptops. And there it was: profit and planet on the same page.

In one shot this story sweeps away epic amounts of false conventional wisdom about the cost and benefits of going green. In Eco Barons: The Dreamers, Schemers, and Millionaires Who Are Saving Our Planet (HarperCollins, 2009), I profile problem solvers who make it their business to vanquish such stupidity through their efforts to help the planet. Their stories show us that opportunities abound if we just shake up our thinking and stop throwing up our hands in despair. So here's an eclectic set of resources to help you start seeing the world like an eco-baron.

First, because it personalizes a mostly invisible global extinction crisis, there's Bruce Barcott's The Last Flight of the Scarlet Macaw: One Woman's Fight to Save the World's Most Beautiful Bird (Random House, 2008). Richly reported and as engaging as any mystery-thriller, Barcott's book is set in Belize, where the indomitable director of the Belize Zoo battles dams and development that threaten to wipe out the nation's last scarlet macaws. The bird "looks like a creature dreamed up by Dr. Seuss," Barcott writes. And the story offers the same stark moral choices that Dr. Seuss poses, though in an adult world of greed, ambition, and Grinch-like investors.

For a fresh perspective on America's insatiable consumerism and its environmental consequences, read Leslie T. Chang's Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (Spiegel and Grau, 2008). An account of the impact our desire for cheap products has had on China, Chang's book unveils the hopes and fears and power of the ambitious women who make your music players, sneakers, cell phones, and Christmas lights--and shows how American demand drives the construction of a new Chinese coal-fired plant every week.

For a fresh perspective on America's insatiable consumerism and its environmental consequences, read Leslie T. Chang's Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China (Spiegel and Grau, 2008). An account of the impact our desire for cheap products has had on China, Chang's book unveils the hopes and fears and power of the ambitious women who make your music players, sneakers, cell phones, and Christmas lights--and shows how American demand drives the construction of a new Chinese coal-fired plant every week.

In The Age of Stupid (Spanner Films, 2009), director, zoologist, and climate activist Franny Armstrong makes compelling cinema of our civilization's trajectory. It's set in the year 2055, in a world wasted by climate change. The main character (an appropriately craggy and cranky Pete Postlethwaite) is an archivist locked away in an enormous tower in a snowless Arctic, where he maintains a record of humankind's history leading up to climate Armageddon. He reviews "historical" vignettes (from our present) that reveal most of us as climate Neros, fiddles in hand. One of the experts highlighted is Mark Lynas, whose book Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet (National Geographic, 2008) spells out the disastrous consequences posed by global warming over the next century.

Christopher Steiner's $20 Per Gallon: How the Inevitable Rise in the Price of Gasoline Will Change Our Lives for the Better (Grand Central Publishing, 2009) explains how the decline of our oil-based economy will force us to change. While naysayers contend that all we have to do is drill, baby, drill to preserve the "American way of life," the fact is that governments around the world are planning for a future of food shortages, unemployment, poverty, emptied suburbia, and a return to local economies. The San Francisco Peak Oil Preparedness Task Force Report makes for some fascinating reading on this score. The best Internet resource on all things oil and energy is the Oil Drum.

Had enough global crisis? Try something more local. Did you know that the opening of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, perhaps the most well-known four notes in the musical universe (dah-dah-dah daaaaah), mimics the song of the white-breasted wood wren? Few of us catch the musical reference, because we don't experience nature as our ancestors did. For a practical analysis of this issue, you can't do better than the updated edition of Richard Louv's Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature Deficit Disorder (Algonquin, 2008), which includes a section with "100 practical actions we can take."

Moving from the outer world to the inner, Nena Baker's The Body Toxic: How the Hazardous Chemistry of Everyday Things Threatens Our Health and Well-Being (North Point Press, 2008) looks at the chemical burden the human body has borne over the past two generations. A good companion read is Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (North Point Press, 2002), by William McDonough and Michael Braungart. Together, the volumes exemplify what drives eco-barons large and small: a willingness to delve into seemingly intractable problems and say, "I think I can fix that." —Edward Humes

Excerpt adapted from Edward Humes's Eco Barons: The Dreamers, Schemers, and Millionaires Who Are Saving Our Planet

(HarperCollins, 2009)

The little Cessna Darted out from under the clouds, and Doug Tompkins got his first glimpse of Renihue Fjord, a misty blue gem in southern Chile, where the Andes tumble toward the sea like an army finishing a long march. It was impossible not to think of fabled Eden in this damp and glorious setting, the world's last intact temperate rainforest.

Tompkins found that the broken-down ranch next to the fjord, along with its spectacular surroundings, was for sale. They'd even throw in the cattle. He could have 24,700 acres for $600,000.

Tompkins tried to keep a poker face: $600,000? You couldn't buy a condo in San Francisco for that kind of money. In Chile--remote, beautiful, wild Patagonian Chile--$600,000 would buy him nearly forty square miles.

"What about the volcano?" Tompkins asked. In the distance, visible from the ranch house windows, stood the cone of the dormant 8,000-foot Michimahuida volcano, snowcapped and heavily forested.

"That's included too, senor."

His own volcano--it was almost too much to grasp. Here the possibilities were endless. Tompkins was in his fifties, his hair gone silver, his face weathered, but he still had time. If he sold his interest in Esprit, he could buy more land than he had ever imagined, with plenty left over to stir up some trouble at home. He could publish books, run full-page ads in the New York Times, dole out grants to environmental groups. And in Chile, he could buy paradise. He could save paradise.

Crash-Test Panda

Sure, an ad showing a panda surviving a car crash grabs your attention. But for U.S. drivers, what may be even more shocking is Italian automaker Fiat's head-on environmental pitch: "Engineered for a lower impact on the environment. The lowest CO2 emission car range in Europe."

Sure, an ad showing a panda surviving a car crash grabs your attention. But for U.S. drivers, what may be even more shocking is Italian automaker Fiat's head-on environmental pitch: "Engineered for a lower impact on the environment. The lowest CO2 emission car range in Europe."

Why aren't our automakers as environmentally focused? Maybe it's because every western European country levies car taxes based on a vehicle's carbon dioxide emissions or fuel consumption. In the United Kingdom, for example, effective April 1, the driver of the cute-as-a-panda Fiat 500, above, will pay as little as £20 ($33) annually for a CO2-based "road tax," starting the second year of ownership. For the privilege of being a planet-hog, a Londoner driving an SUV like the BMW X5 3.0 will pay £550 ($900) in tax the first year and #245 ($400) every year thereafter.

Photos by Michael Darter