sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - july/august 2010 - bulletin | news for members

Bulletin | News for Members

By Della Watson

Grilled | Iowa Eagles Eat Lead | Board of Directors Election Results | Remembering Edgar Wayburn

Grilled:

Invading the Privacy of the Volunteers Who Make the Club Tick

Name: Renee Owens

Name: Renee Owens

Location: El Cajon, California

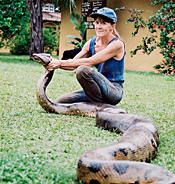

Contribution: : Wildlife ecologist, snake wrangler, and conservation chair of the Club's San Diego Chapter

How'd you end up wrangling anacondas? National Geographic and the Wildlife Conservation Society funded the research in Venezuela. We caught and released more than 900 snakes. The best way to find them was to walk through the swamp barefoot. If you stepped on something, it was either a turtle, a caiman, or an anaconda. We would draw blood, take measurements, and let them go. National Geographic filmed it, then Discovery, BBC, Dateline NBC, and Animal Planet. We were even on Ripley's Believe It or Not.

What did the locals think? They thought we were nuts. They're so phobic of snakes that a lot of them believed we had special mojo. That afforded us a little protection. Sometimes the Venezuelan National Guard would come through and steal stuff from everyone, but they stayed away from our little house because we had snakes. Eventually the locals started learning that tourism brought in more money than anything they had imagined.

So big, scary snakes actually attract tourists? Oh yeah. There's a huge population of people who love them. Some people want to see elephants; some want to see anacondas.

What's the biggest animal you've captured? I think it would be a 600-pound Orinoco crocodile. With help, mind you.

Are you in favor of ecotourism that puts humans in close contact with wild animals? Oh definitely. Now, when we say "in contact," it doesn't mean you have to be the grizzly whisperer. And there are good and bad ways to do ecotourism. Real ecotourism puts money into the local community and supports the whole idea of saving the habitat instead of using it unsustainably.

Obviously, you're not afraid of snakes. What does scare you? Apathy. As long as we're comfortable, people aren't going to demand change. I'm involved with a program that gets kids outdoors, and I've been noticing that one of the most surprising reactions from these kids is fear. As somebody who grew up tumbling around in the mud, I'm frightened by that disconnect—this idea kids now have that nature is something you watch on the Discovery Channel. That it's separate from us. —interview by Della Watson

Do you know a Sierra Club volunteer who deserves recognition? Send nominations to submissions.sierra@sierraclub.org.

Iowa Eagles Eat Lead

Last year in Iowa, hunters shot almost 142,200 deer, but about 10 percent of the animals ran off before they died, and their bodies were never retrieved. That means the lead-riddled carcasses ended up being consumed by scavengers. For eagles, just 200 milligrams of lead—an amount smaller than three baby aspirin—is enough to cause brain swelling, respiratory distress, stomach damage, and seizures. (A 12-gauge shotgun slug contains more than 28,000 milligrams.) California restricts the use of lead ammo for deer hunting in the California condor's range, while a federal ban prohibits lead shot for hunting waterfowl.

"About six years ago it was raining sick and dying eagles," said Kay Neumann, executive director of Save Our Avian Resources, a bird-rehabilitation center based in Iowa. Since 2004, she noted, 60 percent of the approximately 150 eagles in the center's care have suffered from lead poisoning.

With the help of a $3,000 grant from the Sierra Club Foundation, the Club's Iowa Chapter has launched a campaign to persuade hunters to switch to shatter-resistant copper ammo, which eagles tend not to consume. Chapter members have handed out brochures and posters to ammunition dealers and have given presentations to various conservation groups in an effort to get hunters to reload. —Michael Mullaley

Board of Directors Election Results

More than 50,000 Sierra Club members cast a vote to fill the five open seats on the Club's 15-person, volunteer board of directors. As the organization's highest governing body, the board makes decisions about Club policy, governance, and goals. Meet your new and returning board members:

More than 50,000 Sierra Club members cast a vote to fill the five open seats on the Club's 15-person, volunteer board of directors. As the organization's highest governing body, the board makes decisions about Club policy, governance, and goals. Meet your new and returning board members:

- Former board president Allison Chin has been a Club member since 1982. A cancer biologist, Chin worked with the board to promote diversity initiatives and to combat climate change through six conservation campaigns. (38,471 votes)

- Iowa resident Donna Buell fought for clean-water regulations and found funding for water-quality improvements as a state environmental commissioner. An attorney, Buell hopes to expand online fundraising opportunities. (33,116 votes)

- Life member Robert Cox is a professor at the University of North Carolina. A recipient of the William Colby Award for outstanding leadership, Cox helped launch the Club's Training Academy and establish the environmental-justice program. (32,959 votes)

- Jim Dougherty represented the Club at the U.N. climate conference in Copenhagen. The environmental lawyer and veteran board member plans to support and expand the Club's grassroots activism. (30,965 votes)

- The board's youngest member, Jared Duval is the author of Next Generation Democracy. The former national director of the Sierra Student Coalition plans to engage younger members and embrace new technologies for organizing. (30,403 votes)

To recommend a candidate for the 2011 board election, e-mail Mark Walters, Nominating Committee chair, at wwalters@med.miami.edu.

ON THE WEB Learn more about the Sierra Club Board of Directors at sierraclub.org/bod/2010election.

Remembering Edgar Wayburn

Dr. Edgar Wayburn died on March 5, 2010, at the age of 103. The former Sierra Club president left a conservation legacy that includes federally protected redwood groves, lakeshores, prairies, boreal forests, glacial valleys, mountain ranges, coastlines, and natural enclaves in urban regions. The following reminiscence, part of a longer profile written by Harold Gilliam, author and former columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, details events from Wayburn's successful struggle to create California's 75,400-acre Golden Gate National Recreation Area—one of the first urban national parks in the United States. To read the full article, go to sierraclub.org/sierra/wayburn.

Dr. Edgar Wayburn died on March 5, 2010, at the age of 103. The former Sierra Club president left a conservation legacy that includes federally protected redwood groves, lakeshores, prairies, boreal forests, glacial valleys, mountain ranges, coastlines, and natural enclaves in urban regions. The following reminiscence, part of a longer profile written by Harold Gilliam, author and former columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, details events from Wayburn's successful struggle to create California's 75,400-acre Golden Gate National Recreation Area—one of the first urban national parks in the United States. To read the full article, go to sierraclub.org/sierra/wayburn.

On one of Ed Wayburn's regular lobbying trips to Washington, D.C., in 1964, he ran into Representative Phillip Burton in a hotel dining room. Burton, a young San Franciscan who had recently been elected to the House of Representatives, pulled a chair up to Wayburn's table and asked him about his work. That fortuitous encounter turned out to be the beginning of a highly improbable partnership that made conservation history.

Previously, as a member of the California legislature, Burton had earned a reputation as a profane, brass-knuckled, hard-drinking master of the legislative process. Yet he now found an ally he could respect in the quiet, older gentleman from Georgia. He saw Wayburn's vision for a national park at the Golden Gate as a political cause with immense potential. Likewise, Wayburn was impressed by Burton's legislative skill and energy. In time, the two developed a close friendship.

When Wayburn showed up in Burton's office with a map of his proposed national recreation area at the Golden Gate, the congressman asked, "Is this what you want?"

Wayburn's response was equivocal. "Well, we really want something bigger," he said, "but we didn't think it would be feasible in Congress."

Burton bellowed, "Don't worry about what's feasible! Bring in a map of everything you want. I'll handle Congress."

Coming from a young congressman, that remark sounded like braggadocio. But Wayburn later returned with a map proposing a much larger park. With his characteristic go-for-broke attitude, Burton wrote the unlikely plan into a series of bills he tossed into the legislative hopper.

Wayburn, meantime, zeroed in on the administration, keying on the new secretary of the interior, Rogers Morton. But Morton refused to see him. The secretary did not have a high opinion of the Sierra Club, which had opposed his nomination for the job by President Richard Nixon. Like other officials before him, however, Morton found that the Sierra Club president was not easily discouraged. Wayburn kept returning to Washington and finally got into Morton's office.

Morton expected to be presented with some impossible environmental demands and was disarmed by Wayburn's cordial approach and reasonable manner. Wayburn persuaded Morton to take a helicopter tour of the Bay Area to see the potential park for himself. Meanwhile, the National Park Service had developed plans for a pip-squeak park at the Golden Gate, encompassing only Alcatraz and some decommissioned military lands in Marin County.

"The park service wants me to support their plan," Morton later testified to the Senate Interior Committee in favor of Wayburn's alternate proposal, "but I went out there to the site with my friend Dr. Wayburn, and he convinced me."

President Nixon signed "An Act to Establish the Golden Gate National Recreation Area" into law on October 27, 1972. —Harold Gilliam

Photos, from top: courtesy of Renee Owens; iStockphoto/GeorgePeters; Anne Hamersky