sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - january/february 2011 - innovate: power from tides

The swift, powerful tides that can make oodles of electricity are surprisingly rare. In the United States, only a few places—including the Gulf of Maine, Washington's Puget Sound, Manhattan's East River, and the waters under the Golden Gate Bridge—create a muscular flow near cities with sizable power needs. Tide-harvesting devices take advantage of tidal waters impressive power density: Tides can move at twice the speed of waves and can generate eight times the potential energy. But they also carry a vast supply of sediment, larvae, and plankton. As new generator designs reach the ocean floor, they must avoid disturbing marine life.

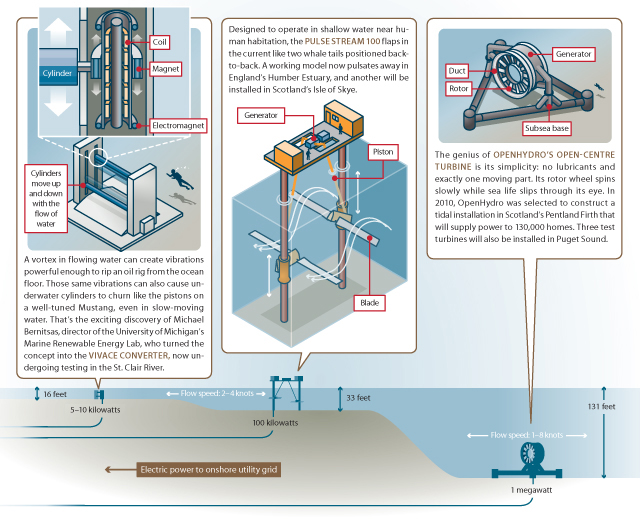

Click to see larger image.

Infographic: Brian Kaas

Huijie Xue grew up in Ruian, a town on China's coast where life moved with the rhythm of the tides. At ebb, the harbor was a carpet of mud; at flood, the fishermen arrived with their catch, followed by the passenger ferry.

Huijie Xue grew up in Ruian, a town on China's coast where life moved with the rhythm of the tides. At ebb, the harbor was a carpet of mud; at flood, the fishermen arrived with their catch, followed by the passenger ferry.

As a teenager, Xue read a newspaper article about a tidal barrage (a sort of estuary-spanning hydroelectric dam) being built halfway around the world in Nova Scotia. The idea of getting electricity from the tides wouldn't leave her mind. When she stepped on a ferry to head to college—at high tide, of course—it was to study oceanography.

Now Xue, 45, is an expert in the computer modeling of tidal currents. She works at the University of Maine, not far from the barrage in the Bay of Fundy that first inspired her, and confronts one of the most difficult problems in marine energy: How do electricity-generating turbines affect tides and the life that depends on them?

Few waterways boast more energy potential than the Gulf of Maine. Tides rise and fall nearly 50 feet, pushing between dozens of islands and accelerating currents to as fast as six knots. The Ocean Renewable Power Company, based in Portland, Maine, is testing its lawnmower-like turbines in gulf waters and is laying plans for a billion-dollar electricity industry. But the gulf is critical to the states fishing industry, so ORPC relies on Xues research to gauge the impact.

"We're trying to get a very small percentage [of the gulf's energy], but that doesn't mean the impact is small," Xue says. "For example, if in Cobscook Bay we take 15 percent of the energy out of the main waterways, what's the impact? We really don't know." —David Ferris