Photo by Beth Rooney

Photo by Beth Rooney

By Jake Abrahamson

Simi Olabisi can't remember the day she nearly died. But she knows the story by heart. Her dad tells it all the time.

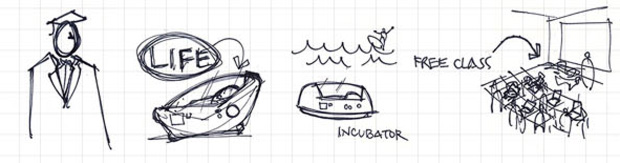

Olabisi was born two months premature—a tiny, barely breathing thing. Definitely in need of an incubator. But the Lagos hospital she was born in, like much of Nigeria, lacked working incubators. "With babies like me," says Olabisi, now 23, "they normally wrap you up and hope you'll live."

There was a children's hospital on the other side of Lagos, so her father scooped up his new daughter and started moving. He managed to flag down a taxi, but they came to a standstill in traffic, so he jumped out and ran several miles through the baking streets. Thanks to his efforts, Olabisi made it into an incubator and survived.

During her adolescence, she and her dad, a chemical engineer, discussed the possibility of an incubator that would be immune to the electrical outages so common throughout the developing world. Unfortunately, reliable solar-powered models cost around $30,000, an amount that's not affordable in rural Nigeria, where 80 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

After years of globe-trotting (her dad's work took them from Nigeria to Saudi Arabia to Texas), Olabisi enrolled in California's Santa Clara University, where she studied bioengineering. When she had to come up with a senior project, pieces clicked. This was her chance—and her kick in the butt—to pursue what she and her father had talked about. "Without the senior project," she says, "I don't think I'd have gone after this."

Olabisi recruited six other seniors studying different kinds of engineering, and they leveraged their student status to get the resources they needed: Santa Clara University granted $7,400 plus lab space. San Francisco General Hospital donated one of those pricey incubators. Chromasun gave them a panel, and Solar Way Forward offered a free photovoltaics class.

"We approached everyone who helped us out from the angle that we were university students," she says. "That definitely got people's attention."

The group called itself Team Omoverhi, which means "lucky child" in the southern Nigerian language of Urhobo. The four mechanical engineers designed the machine components. An electrical engineer oversaw everything solar-related. Olabisi and a fellow bioengineer developed monitoring systems and kept things infant-friendly: "Sometimes a mechanical engineer would suggest using materials, and I'd say, 'We can't use that. It would burn the baby.'"

To cut the cost down to $2,000, they replaced maneuverability buttons with props and levers, used salvaged computer fans, and made the bed out of a lunch tray. It wasn't yet ready for market, but they had a prototype of a solar-powered neonatal incubator.

Then, in 2011, everyone graduated. Olabisi moved to Chicago, where she now works with semiconductors.

But the project wasn't dead. Santa Clara University, acting as a sort of incubator itself, fostered a smooth handoff to a group of rising seniors, and the original Team Omoverhi became the progenitor of an ongoing project. The class of 2012 shaved dollars and improved efficiency by coming up with a new solar-energy storage system that uses wax-filled pipes (the original design used water). The pipe system costs roughly $45 (down from the water-based system's $250), and most of the materials are commonly available in dump sites.

"The reason we're in this field is to make a positive difference," Olabisi says. "I don't plan to let this idea die. Hopefully we can implement it around the world."

DROP OUT? READ THE FLIP SIDE.

Illustrations by Timothy J. Reynolds

Rural mothers become solar engineers.

Turn a plastic bottle into a stylish charging station.

Loves kids, hates chemicals.