sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - jan/feb 2013 - solar for all

Until now, rooftop solar has only worked for those with hefty electric bills and sunny roofs. Community solar could make it available to everyone.

By Paul Rauber

"We found that the greatest benefit for the consumer was always realized in the case where they owned the panel," Spencer says. He admits that it would have been easier to adopt a lease-financing model, like that used by Sungevity and others, to market solar arrays to individuals. But just as with those personal rooftop systems, outright ownership of a panel in a solar garden gives a better rate of return than does leasing. So if we do start that solar garden on top of the rec center, I would own a panel, Doris would own a panel, and the cat lady would own three because she has to run the can opener so much.

The tricky part, Spencer says, was figuring out how to take advantage of the federal tax credit. "The IRS tax code," he notes dryly, "was not written to support community solar." For instance, it doesn't allow individuals to take the credit if the solar equipment isn't physically on their property. Since the corporate tax code does, the Clean Energy Collective holds technical ownership of the panel for five years, sells the tax credits to someone who can use them (usually a big bank), and discounts the up-front expense to consumers accordingly—which allows them to buy in for as little as $525.

"We hope to show that solar is not only economically viable; it's also profitable."

Once the solar garden starts producing, the project's customers receive a straight dollar credit on their utility bills. This is different from the usual arrangement for individual homeowners with rooftop panels, most of whom take advantage of a policy called "net metering": When the sun is shining, their electric meters spin backward. They get credit for the power they produce, but only up to their average electricity usage. Power produced beyond that just goes into the grid—and typically at a time of day when electricity demand is highest and power the most valuable. That's why the policy is popular with utilities.

Some community solar advocates would like to adapt this system to solar gardens via a policy they call "virtual net metering" or "community net metering." In my neighborhood's case, this would require our utility to credit me, Doris, the cat lady, and all the other co-op members for the energy produced from the panels on the rec center. That would do the trick, but utilities hate it. The Clean Energy Collective model avoids this fight entirely by simply selling power to the utility as if the collective were operating a small power plant. Doing so, Spencer says, "allows us to speak their language." The utility doesn't have to change its accounting practices to credit the community solar members because Spencer's group provides metering software that takes care of everything. The simplicity of this arrangement leads solar expert Farrell to call the Clean Energy Collective the "only consistently replicable community solar model." It now has 14 projects totaling 5.3 megawatts operating or under construction in Colorado, New Mexico, and Minnesota.

"We're one of the only solar companies I know that actually partners with the utility, as opposed to shoving it down their throat," Spencer says. "You have to understand their mentality. Why not allow everybody to win? Utilities meet their goals, consumers meet their goals, and we end up with a hell of a lot more solar." That, after all, is community solar's goal—to provide more solar in general, not necessarily for particular individuals. Electrons from the panels on the rec center wouldn't necessarily flow into my toaster, but they would increase the total amount of solar power in our town—and hopefully make me some money too.

Hitting community solar's sweet spot from another angle is Oakland, California-based Mosaic. Housed among a host of other solar start-ups in the airy waterfront offices of solar-leasing giant Sungevity—imagine big views of the San Francisco Bay, lots of laptops, and exercise balls instead of chairs—Mosaic crowd-funds solar projects, enabling people to invest directly in small to midsize solar projects while earning annual returns of 4 to 8 percent.

Financing is a major hurdle for community-scale solar. Very few banks finance solar projects, and those that do favor big ones—either utility-scale solar operations or solar-leasing companies that front thousands of rooftop projects. When it comes to serving the needs of Oakland's Asian Resource Center or St. Vincent de Paul Society, or the Murdoch Community Center in Flagstaff, Arizona, it's not worth the banks' time to do the risk analysis involved.

Enter Mosaic. In the case of St. Vincent de Paul, it rounded up 80 supporters who kicked in a total of $88,000 to finance 26 kilowatts of solar panels to power the organization's kitchen, where volunteers prepare a thousand meals a day for Oakland's homeless and indigent. All those walk-in freezers and refrigerators require a lot of electricity, says St. Vincent executive director Philip Arca. The solar panels are saving about $1,200 a month, he says, adding, "We want to get as much assistance to people as possible, so for us every dollar counts."

This project, like Mosaic's other early endeavors, was a test in which the "investments" were actually zero-interest loans. A new project, installing 47 kilowatts of panels on the roof of Oakland's Youth Employment Partnership, a job-training nonprofit, is Mosaic's first to offer a real return on investment—in this case, an attractive 6.38 percent. At present, the Securities Exchange Commission is limiting the offering to no more than 35 "non-accredited" investors (i.e., ordinary folks as opposed to millionaires), since it considers the offering to be speculative. Mosaic has been involved in lengthy negotiations with the SEC, says the company's "community builder," Lisa Curtis, trying to get a more general approval of its model, which would open up solar investments to the public at large.

"We think of ourselves as a solar finance company," Curtis says. "Our model recognizes that we now have the power of the Web to bring people together—so people in Michigan, for example, a place without great solar resources, could still put their money to work creating clean energy. We hope to show that solar is not only economically viable; it's also profitable."

Should Mosaic get SEC approval—which it is confident will be forthcoming—to offer shares in community solar facilities to ordinary investors at interest rates of 4 to 8 percent, Farrell says, that would be a game-changing advance. "If it becomes relatively inexpensive to raise capital for community-based projects," he says, "that really blows the door down."

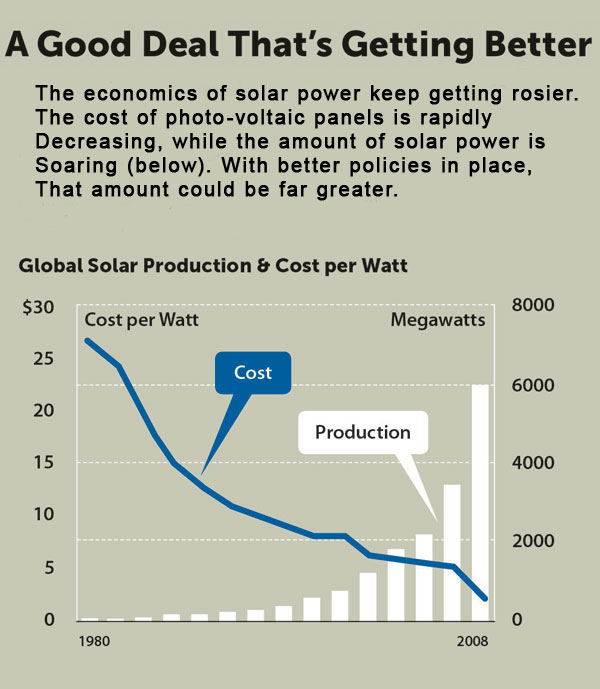

Graphics source: Green Econometrics

1 | 2 | 3 | next >>