sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - january/february 2009 - building better: a/c b.c.

Building Better: A/C B.C.

How Americans lived well before we had energy to squander

By Peter Frick-Wright

Recent efforts to make homes more Earth friendly are enough to make a technology geek swoon. Choose from solar-cell panels, wind turbines, geothermal heating, automated ventilation, and wastewater heat-exchange systems, and you can wire your home for the high-tech, low-energy 21st century. Even more-radical innovations loom on the horizon.

These Star Trek technologies are only embellishments on ideas hundreds of years old, developed by people who didn't have the option of flicking a switch when they were too cold or too hot. For winter lows, insulate your house well and design compact spaces that can be heated efficiently. For summer highs, face windows south, shade your house from afternoon sun, allow hot air to escape from upper floors, and design interior spaces to catch rather than block breezes. Oh, and maybe enjoy a cold drink or a midday siesta on the veranda.

Built before there was a grid to be off, the buildings described here offer a template for a time when cookie-cutter houses plopped onto lots without heeding the sun or wind will go the way of geodesic domes and every new dwelling will be designed with the utility bill in mind.

A mint julep might be an effective way to keep cool in the hot and humid tobacco belt, but builders throughout the South employed other measures that were just as refreshing.

A mint julep might be an effective way to keep cool in the hot and humid tobacco belt, but builders throughout the South employed other measures that were just as refreshing.

Taking their cue from Caribbean architecture, builders in Charleston, South Carolina, designed homes with large windows facing the ocean to catch sea breezes. Deep overhangs allowed windows to stay open even during rainstorms; bermuda shutters let air through and blocked the sun.

Every floor had a veranda and an open stairway to the upper levels to pull hot air out of the house. "Builders added porches to the southwest side of the house, where residents could sit in the shade," says Ken Harkins, president of the American Institute of Architects' Charleston chapter. "They weren't dumb."

But despite the ventilation, wood had a tendency to rot in the wet air. So Charlestonians in the 18th and 19th centuries turned to cypress trees, an extremely rot-resistant hardwood growing throughout the local swamps. "Other than 50 coats of paint, it's the same siding on those houses today," Harkins says.

Before central air-conditioning, before window-mounted A/C units, before kitchens even had freezers in which to chill a pair of undies, the people of the Southwest needed a way to tame the heat.

Before central air-conditioning, before window-mounted A/C units, before kitchens even had freezers in which to chill a pair of undies, the people of the Southwest needed a way to tame the heat.

Adobe mud was not only an abundant building material throughout the arid Southwest, but the thick, dense bricks also added thermal mass to houses, moderating temperatures by insulating living spaces.

Facing extreme temperatures both day and night, south-facing walls had to be especially thick. In a perfect system, the adobe absorbs heat during the day while keeping the interior cool, then radiates heat into the home at night.

Architectural historian Abigail Van Slyck notes that 19th-century Tucson residents hung wet sheets in a central corridor to evaporate and cool the dry desert air. They functioned much like swamp coolers. Van Slyck extols the advantages of evaporative-cooling methods, old and new: "You don't have that feeling of living in some kind of hermetically sealed environment that you get with A/C," she says.

When it came to designing houses for long New England winters, the Pilgrims built with a religious attention to functionality.

Walls were 12 solid inches of bricks and mortar with tiny windows (to save heat) and south-facing entrances. Roofs had steep angles with the dual purpose of shedding winter snow and trapping warm air in the upper floors where bedrooms were located.

In the northern states, a central fireplace, its chimney rising through upper floors, trapped heat inside the house. The Southern version of the same house, meanwhile, might have its chimney located at one end of the building, to sap heat in the summer.

The warmer southernmost room was often used for those who fell ill or needed extra care; ornamental window hoods also kept out rain, snow, and the hot midday sun.

When it came to designing houses for long New England winters, the Pilgrims built with a religious attention to functionality.

Walls were 12 solid inches of bricks and mortar with tiny windows (to save heat) and south-facing entrances. Roofs had steep angles with the dual purpose of shedding winter snow and trapping warm air in the upper floors where bedrooms were located.

In the northern states, a central fireplace, its chimney rising through upper floors, trapped heat inside the house. The Southern version of the same house, meanwhile, might have its chimney located at one end of the building, to sap heat in the summer.

The warmer southernmost room was often used for those who fell ill or needed extra care; ornamental window hoods also kept out rain, snow, and the hot midday sun.

Peter Frick-Wright is a writer in Portland, Oregon.

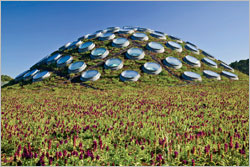

Atop San Francisco's California Academy of Sciences.

Living roofs are literally a growing trend. They're now found at the University of Illinois; Golden Gate Park and Gap headquarters in San Francisco; a Ford factory in Dearborn, Michigan; and soon much of downtown Chicago.

Rooftop plants detoxify rainwater, provide habitat for birds and bugs, and absorb radiating heat. The roof of Chicago's City Hall, which was recently retrofitted with greenery, stays 25 to 80 degrees cooler than surrounding roofs in summer.

In Germany, where homeowners are charged for polluted runoff, living roofs have been popular for decades. "They've had a focus on stormwater management for a long time," says Stuart Berg of Roofscapes Incorporated, a "green roof engineering" firm in Philadelphia. "We're just starting to realize how important it is."

Living-roof systems can be modular (small puzzle pieces that fit your roof) or monolithic (covering the entire roof at once). Both consist of a layer to protect the waterproof roof, another of rocks or plastic to allow drainage, and finally engineered "growth media" (read: dirt) without fine particles or organic matter that cause clogs.

Plants go on top, and owners can choose to tend their green space or not. "On a 1,000-square-foot green roof, you can expect four hours of maintenance a year," Berg says. Or you can let nature take its course. In terms of stormwater abatement, "weeds will probably do a better job than regular plants," he says. —Peter Frick-Wright

Mini-modern: Tumbleweed Tiny House Company's 392-square-foot Z-Glass house.

Wisecracks about low overhead aside, many Americans are embracing the idea that a bigger home is not always better. Concerns about carbon footprints and energy costs mean that where McMansions once sprouted, a small-house movement has taken root. Just ask Brad Kittle, who runs Tiny Texas Houses, a company specializing in very small dwellings--the largest has a 12-by-28-foot floor plan--constructed almost entirely from salvaged wood. In 2007, Kittle built four homes. This year he built ten. And he plans to start leading tiny-house-building seminars. "I can't build enough to keep up with demand," he says.

Kittle is not alone when it comes to diminutive home design. The blogosphere buzzes with tales of individuals living in micro-structures of less than 100 square feet.

Of course, not everybody wants to downsize so radically. That's one reason architect Sarah Susanka advocates that people tailor their expectations according to comfort, not sacrifice. A small-living guru, Susanka is author of The Not So Big House (Taunton, 1998), recently updated for its tenth anniversary. "Each household is different," she says. "Basically, the ideal house is a third smaller than what people think they need. I tell them, if you live with less space, you get a lot more bang for your buck."

That message resonates. Gopal Ahluwalia, vice president of research at the National Association of Home Builders in Washington, D.C., believes that between the mortgage meltdown and the green building boom, the door is closing on crazy-big houses. "We're seeing a trend toward stabilization," he says. "I don't think the size will go up any more." —Dan Oko

Illustrations by Tim Bower; used with permission.

Photos, from top: Tom Fox, SWA Group; Tumbleweed Tiny House Company; used with permission.