sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - march/april 2009 - killing king coal

Killing King Coal

Dick Cheney's energy plan opened the door to hundreds of new coal-fired power plants. Once on line, they'd make catastrophic global warming virtually inevitable. With little hope of success, a scrappy band of activists figured they'd see if they could block one...

By Scott Martelle

The existing 360-megawatt Holcomb Station power plant in Garden City, Kansas, burns 1.5 million tons of coal from Wyoming's Powder River Basin each year. Its operators sought to sextuple its output.

A History of American Coal

1300s

Hopi Indians used coal for cooking, heating, and to bake clay pottery in what is now the southwest United States.

1673

Louis Jolliet discovers coal in Illinois.

1748

First commercial U.S. coal production from mines near Richmond, Virginia.

1800

Coal is harnessed to power industrial processes, steamships, and trains.

1860s

Coal is used in Civil War weapons factories.

1870s

Coal becomes the primary fuel for iron blast furnaces manufacturing steel.

1873

"King Coal" is born, as wealthy railroad mogul Franklin B. Gowen buys several coal mining companies and forms a cartel. (Gowen's rail holdings are memorialized in the four railroads in the Monopoly board game.)

1875

Gowen's cartel dominates anthracite coal production. He cuts miners' wages, bringing on a series of bloody strikes. Bosses beat and kill countless miners, who in turn derail trains, sabotage machinery, and burn down mines.

1882

Thomas Edison develops the first coal-fired electric power plant in New York City. Residents complain about soot, so most future plants are built outside cities.

1897

The Lattimer Massacre takes place near Hazelton, Pennsylvania. During a peaceful demonstration against poor working conditions and low wages, county sheriffs kill 19 immigrant miners.

1902

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) orchestrates a large strike in the anthracite mines of eastern Pennsylvania. President Theodore Roosevelt intervenes and guarantees the miners higher wages and better hours, though their union was still not recognized as a bargaining agent.

1910s

Mechanization comes to coal mining with the introduction of the conveyor belt, and many laborers are replaced by machines. (By 1940, 70 percent of West Virginia coal loading is done by machines.)

1914

The Ludlow Massacre follows a strike by the UMWA at this Colorado coal mine.

1927

Miners with the Industrial Workers of the World union strike in Serene, Colorado, leading to the Columbine Mine Massacre.

1930s

Developing oil and gas technologies diminish the demand for coal.

1945

The anthracite coal industry starts to collapse.

1952

Across the pond, the Great Smog of coal smoke in London kills 4,000 people in four days.

1970

The Clean Air Act and the new EPA target airborne pollution. The worst culprit is sulfur dioxide (S02), a byproduct of coal combustion that causes acid rain.

1970s

Softer, lower-quality bituminous coal replaces anthracite. Oil shortages spur demand, leading to the first mountaintop-removal coal mines.

1975 to 2002

Nearly all new U.S. power plants in this era are fired by natural gas, not coal.

1990

Congress enacts the Acid Rain Program to slash SO2 emissions. One consequence is a shift to low-sulfur coal (found mainly in the West) rather than high-sulfur coal from the East.

2000s

President George W. Bush's election brings a resurgence of coal power plant construction.

2003

Bush funds the FutureGen Alliance's "clean coal" carbon capture and storage project. Its funding was decreased in 2004, reinstated in 2005, and cut completely in 2008.

2008

Barack Obama is elected president. During the campaign, he supported "clean coal" and the construction of five new carbon capture and storage coal plants.

Barbara Percival had never been particularly political. She barely noticed nearly 30 years ago when the Sunflower Electric Power Corporation began building its 360-megawatt Holcomb Station power plant a few miles west of her wood-frame house in Garden City, Kansas. Most everyone thought the jobs would be good for the town, which otherwise relied on the vagaries of weather and farming on southwest Kansas's windswept prairie.

Worried about health effects, Barbara Percival took the unpopular position of opposing expansion of the Holcomb Station coal-fired plant.

But over time Percival, 78, began paying more attention to the health of the world around her. Cancer helped the evolution. Seven years after Alzheimer's claimed her husband, Percival was diagnosed with breast cancer and had a double mastectomy in 2006. "The neighbors next door, both of them have had cancer," Percival says, settled into her living room armchair, the front door open to brilliant morning sunshine.

"One across the alley died of cancer. Another one down the street died. Another one had cancer, and she's still alive." Percival began to suspect that something in the environment might be to blame. So when she read in the Garden City Telegram three years ago that Sunflower wanted to add three more 700-megawatt coal-fired plants at Holcomb, one word came to mind: No. It was not a popular reaction in conservative, pro-growth Garden City. "Everybody wants the plant," she says. "Even my older son, and he lives out there." Percival, a retired widow without political connections, had no way to fight it. So she fretted in silence, wishing someone, somewhere, would take on the power company.

Club volunteers Craig Volland and Bill Griffith at Leavenworth's High Noon Saloon, where the showdown with Holcomb began.

As it happened, on the other side of the state, three Sierra Club activists huddled over beers at a corner table of Leavenworth's High Noon Saloon considering how to do just that. Word of the proposed $3.6 billion Holcomb Station plant, which if completed would spew up to 6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year, had raced through the small network of Kansas environmental activists.

Given the state's pro-business politics, few thought they could do much to stop it. But lack of hope doesn't necessarily equal despair. Bill Griffith, a prison special-ed teacher and then Kansas Chapter chair; then-attorney and Club lobbyist Charles Benjamin; and volunteer air-quality expert Craig Volland figured that even if they couldn't beat the Holcomb proposal, they could at least slow it down.

Changing the course of history often involves being in the right place at the right time. When the time isn't right, sometimes you have to wait until it is. The Sierra Club activists didn't know it, but the planets were aligning in their favor.

Ever since the neolithic Chinese discovered how to burn black rocks, coal has been an integral part of humans' relationship with their environment. Used across civilizations for heat and cooking, coal became the cheap and plentiful fuel of choice to drive the turbines of the industrial revolution. By the 1880s, thanks to Thomas Edison, coal also powered the first electric dynamos.

Coal was never the modern world's sole energy option. Hydropower ran the earliest mills, and electric power from dams on the Colorado and Columbia Rivers helped industrialize the West. As far back as the mid-1800s, enterprising Kansans were flirting with wind power: Blacksmith Samuel Peppard achieved modest fame in 1860 when he tried to sail his "wind wagon" to the Colorado gold fields, though a little too much wind destroyed the wagon en route. Plains farmers were more successful in harnessing the relentless gales to pump water, and recently wind-powered turbines have sprouted in Kansas cornfields.

Still, coal remains the nation's prime source for creating electricity, and it enjoys the benefits of a rich and powerful lobby and the support of politicians of both parties in the many states where it is mined. Nationwide some 1,500 coal-fired generators kick out 335,000 megawatts of power and more than 2 billion metric tons of CO2, accounting for 36 percent of the country's total production of that planet-heating gas.

If the coal and electric industries have their way, those numbers will increase dramatically. Following the recommendation of Vice President Dick Cheney's secretive energy task force, in 2003 the Bush administration loosened enforcement of environmental regulations regarding electricity production. The result was a flood of proposals for more than 180 new coal-fired power plants across the country. If all were built, the fight to stop global warming would effectively be lost. Their combined CO2 emissions would swamp any conceivable conservation effort. Their global-warming impact would be greater, for example, than that of all U.S. cars. In addition, a dramatic surge in U.S. CO2 production would give India, China, and other nations a perfect excuse to abandon efforts to reduce their own emissions.

Bruce Nilles, director of the Sierra Club's National Coal Campaign: "I realized that our focus on soot and smog was missing the global- warming problem."

Hardly anyone noticed what was happening. One who did was Bruce Nilles, then director of the Sierra Club's Midwest Clean Energy Campaign in Madison, Wisconsin. In 2003, MidAmerican Energy Company, based in Des Moines, Iowa, had received approval--without public opposition--for a $1.2 billion, 790-megawatt expansion of its Council Bluffs Energy Center. At the time, the Club and most other environmental groups were still focusing on traditional toxic pollutants like mercury and sulfur dioxide and paying scant attention to CO2, an unregulated byproduct of coal burning that was not addressed in the permitting process. Nilles, however, was growing deeply concerned about global warming, and he calculated how much CO2 the new plant would produce. The answer came as a shock: 6.2 million metric tons a year.

"I realized that our focus on soot and smog was missing the looming global-warming problem," Nilles says.

Most coal-fired plants receive operating permits through state agencies, so the deluge of new applications was going largely unnoticed nationally. Nilles alerted journalists at the Christian Science Monitor and the Chicago Tribune to what was soon dubbed the "coal rush."

Up to that point, the Sierra Club had been fighting coal-plant proposals piecemeal. Nilles merged those scattered efforts into the National Coal Campaign, combining local grassroots political muscle with the Club's legal firepower. The fight was on hostile terrain, given the Bush administration's stalling on climate change. In Kansas, it became a showdown over whether the state could reject the Holcomb Station proposal on global-warming grounds, even though CO2 regulations did not yet exist.

Word of Holcomb's expansion first leaked out, ironically, as environmentalists tried to nurture Kansas's nascent wind power industry. In early 2005, Benjamin, the Club's Kansas lobbyist, was working in Topeka with legislators to create a state authority for the network of new power lines that the wind turbines scattered over the prairie would require. But a key legislator told Benjamin that the transmission authority was going to be not just for windmills, but also for new coal plants. "I told him that we would fight the coal versus renewable energy battle separately," says Benjamin. "So I had some hint that plans were afoot to build new coal plants in western Kansas, but I didn't know the details."

Those details came later that year, when Sunflower announced that it had struck a deal with a Colorado utility to add two 600-megawatt plants at Holcomb. By the time Sunflower filed a preliminary air-permit application with the Kansas Department of Health and Environment in February 2006, the project had expanded to three 700-MW generators, using coal brought in by rail from Wyoming's massive Powder River Basin open-pit mines. The new plants would be among the largest west of the Mississippi River, and would be built and operated under a complicated set of arrangements that would route power to customers in Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and New Mexico. Sunflower would operate all three units, but the vast majority of the power generated at Holcomb would leave the state.

Then-Kansas Chapter lobbyist Charles Benjamin feared jobs would trump all at Holcomb: "I don't see a scenario where a permit is going to be turned down."

Then-Kansas Chapter lobbyist Charles Benjamin feared jobs would trump all at Holcomb: "I don't see a scenario where a permit is going to be turned down."When Sunflower's dramatic expansion plans became public, local Sierra Club activists scrambled to figure out how to respond. Griffith and Benjamin set up the meeting with Volland at the High Noon. They saw few open options. In a state of 2.8 million people, the Club chapter has something over 4,000 members, most living around Kansas City and near the university towns of Lawrence and Wichita. Given the state's political and cultural divide--the west's conservative and job-hungry rural areas versus the more urbanized and liberal east--it wasn't a likely environment for a successful grassroots campaign.

Nor could the Sierra Club expect much help from the Democratic governor, Kathleen Sebelius, who appeared resigned to the coal plant. In fact, her refusal to fight the project--she had ignored the Club's request that she declare a moratorium on new coal-fired plants--cost her the Club's endorsement in her nevertheless successful 2006 reelection campaign. Griffith and the others assumed they would ultimately have to fight the permit in the courts and hoped to draw out the process, reasoning that any delay to a huge new source of CO2 was good for the environment.

First, however, activists had to navigate the public process. Before the Kansas Department of Health and Environment could issue air permits for Sunflower's Holcomb proposal, it had to hold a public hearing. The agency scheduled the hearing in Garden City, near where the plants would be built but hundreds of miles from population centers in eastern Kansas. After lobbying by Benjamin, other environmentalists, and friendly state legislators, the department added public hearings in Topeka and the liberal enclave of Lawrence.

The first hearing in Garden City, in October 2006, drew nearly 100 people, 90 percent of them in favor of the plant. Local elected officials also supported the proposal, which had lots for them to like, including 2,000 temporary construction jobs and another 140 or so permanent positions operating the expanded facility.

The second hearing two days later drew about 120 people to Topeka, where supporters again seemed to have the upper hand. Benjamin was convinced the state would grant the permit. "They're desperate for jobs out there," he told reporters at the time. "I don't see a scenario where a permit is going to be turned down."

Even with the odds on their side, coal plant backers left nothing to chance and bused a few dozen supporters from the western part of the state to the next hearing in Lawrence. When local residents arrived just before 6 p.m. at the University of Kansas campus, they found most of the seats already taken, forcing them to listen via loudspeaker from a spillover room.

The coal-backers' tactic annoyed Lawrence locals, Griffith says. "For us it was great. I started laughing when I saw what Sunflower did. I thought it was a big mistake."

More significant than goading Lawrence environmentalists was the critical mass drawn to the hearing: More than 300 people signed in, leading regulators to add a fourth hearing the next night. Sensing the anger, Griffith, Benjamin, and the others began to think they might have a chance at stopping the project politically, rather than rolling the dice in court. That night they began pulling together a coalition that eventually included, among others, the True Blue Women Democratic club, the Kansas Natural Resource Council, and the Sustainable Sanctuary Coalition. There was also growing interest from Wes Jackson's Land Institute in Salina, a groundbreaking research group working to balance prairie ecology and agriculture.

The coalition's first test came two weeks later on December 2, a clear and brisk morning in eastern Kansas. Griffith was up early at his home in Leavenworth, and after breakfast he began the hour-and-a-half drive to the State Capitol building in Topeka. As its first public act, the fledgling coalition organized a rally on the capitol steps to show Sebelius and state regulators that not all Kansans thought the lure of new jobs compensated for raising average temperatures in the state (according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) nearly 7 degrees by 2100.

Griffith didn't know what to expect as he neared the capitol. "It was a nice winter snap that morning," he says. "I was kind of worried how many people would show up, because we knew the TV cameras would be there."

By the time the speakers began, a hundred people had gathered. It wasn't a huge crowd, but it was big enough. "It was a Saturday morning, three TV stations there," Griffith says. "It was putting some pressure on the governor. The folks there were the folks who voted for her."

Hope began to grow.

After the holidays, the Kansas activists got to work. They started a letter-writing campaign to the governor pushing wind power--a seemingly endless source of energy on the Great Plains--as an alternative. And they prepared for what they assumed would be a drawn-out legal fight once Kansas issued the permits.

"We can take credit for raising consciousness around the state among our network of environmentalists," says Volland, the Kansas Chapter's air-quality expert. "Other players came in. It gave us more capacity to fight this battle."

The Land Institute joined and formed the Climate and Energy Project to "halt the Midwest's contributions to global warming and climate change." Earthjustice came in on the legal front. Meanwhile, the broader political landscape had begun to change in the wake of Al Gore's 2006 documentary,

An Inconvenient Truth, which brought fresh attention to global warming and helped galvanize progressives and environmentalists. Sebelius's national profile had also grown, and she started to be touted as a potential vice presidential candidate. Approval of the Holcomb project wouldn't exactly enhance her image with environmentally aware Democrats.

The legal landscape too was shifting. After the Bush EPA decided in 2003 that the Clean Air Act didn't cover CO2 emissions, Massachusetts and several other states filed a legal challenge, arguing the gas is a pollutant to be regulated and that the states would be affected by rising seas and other consequences of global warming. The states lost in the lower courts, but in June 2006 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. Sierra Club senior staff attorney David Bookbinder and Earthjustice made their oral arguments November 29--just days after the Lawrence public hearing.

Few environmentalists held out hope that the conservative court would back additional regulations. But the case helped mobilize states and other lower-level governmental bodies into a coalition of their own to try to fill the regulatory void left by federal inaction. Prodded by the Sierra Club, attorneys general for eight states from California to Maine urged Kansas to reject the Holcomb Station expansion, arguing it would undermine their own efforts to control greenhouse-gas emissions.

On April 2, 2007, the Supreme Court surprised everyone by overruling the EPA and declaring greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, pollutants subject to control under the Clean Air Act. The decision opened a door to challenge the Holcomb permit outside the usual appeals over heavy-metal pollutants that, in most cases, delayed projects but didn't stop them.

"The ground just kept shifting underneath us, and it kept shifting in our direction," Griffith says. "We thought, 'We can get this thing denied.'"

In August, Sebelius signaled that the Holcomb air-permit application might be in trouble, telling the Wichita Eagle's editorial board that she opposed the expansion (by then scaled back to two 700-megawatt units) but that the decision was in the hands of the Department of Health and Environment. Two months later, armed with the Supreme Court decision and an advisory letter from the state's attorney general that he had the authority to declare unregulated CO2 an environmental hazard, department head Roderick Bremby overruled a staff recommendation and denied the air permit.

In announcing his decision, Bremby cited the risk of global warming. "It would be irresponsible to ignore emerging information about the contribution of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to climate change, and the potential harm to our environment and health if we do nothing," he said.

Griffith was home, glued to his computer, when the decision popped up on the department's Web site. "I let out a war whoop," he recalls. "I had to just kind of sit there for a couple of minutes and blink."

The battle was won, but more skirmishes were yet to come. In March 2008, the Republican-dominated Kansas legislature tried to strip Bremby of his authority to deny the permit; the Sierra Club and its partners applied pressure on legislators to back the governor. Even Percival, the Garden City woman who had worried in silence over the proposal when it was first announced, felt emboldened to write a letter to the editor of her local newspaper.

Twice the legislature passed laws reversing Bremby's decision to regulate CO2, and twice Sebelius vetoed them. The state Senate voted to override the vetoes, but leaders in the state House of Representatives couldn't muster the votes. A third try was aborted when it became clear that it too would fail.

"The fact that we were able to stop Holcomb," Volland says, "is nothing short of a miracle."

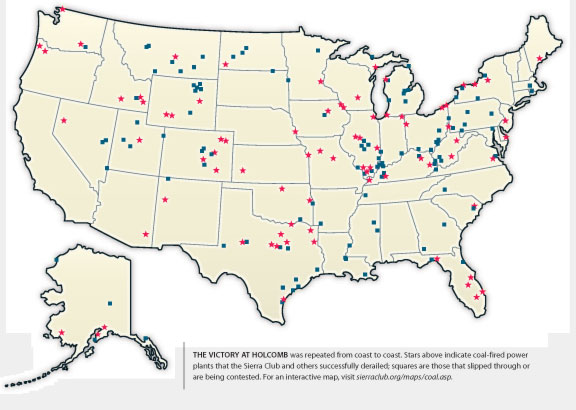

The miracle extended beyond the Kansas prairie. By the end of 2008, the Sierra Club and its allies had shut down proposals for 81 other coal-fired power plants that would have pumped an additional 317 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, about 5.3 percent of the nation's current output.

The coal industry's massive project was teetering but not yet out. The next blow would come after Sierra Club senior staff attorney David Bookbinder found himself with a little extra time on his hands and hit on a novel way to stop a proposed coal plant on a remote Native American reservation in eastern Utah.

To be continued in the May/June issue of Sierra.

Scott Martelle is a former staff writer for the Los Angeles Times and author of the critically acclaimed Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West.

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's National Coal Campaign. For more information, visit sierraclub.org/coal.

This article has been corrected subsequent to publication.

Photos, from top: Jolies Images (2), Jason Dailey, Scott Suchman, Matt Theilen