sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - march/april 2010 - grapple

Grapple | With Issues and Ideas

The Future of Garbage | Up to Speed | Not a Lot of Axolotls | Global Conspiracy | Woe Is Us |

As the World Warms | Et Tu, Exxon?

The Future of Garbage

Your trash can is the latest front in the fight against global warming

Instead of producing methane in landfills, these former table scraps and yard trimmings will nurture California farms and vineyards.

Three days a week, M. Lee Meinicke, cofounder of Philly Compost, takes her truck on a circuit of Philadelphia restaurants, caterers, and markets, filling 20-gallon bins with plate scrapings, aging produce, chicken bones, food-stained napkins, and other discarded organic matter. The waste will be served up as dinner to Meinicke's stable of red wigglers and night crawlers, emerging on the other end as compost that she will sell for $15 per four-gallon bin. She turns straw into gold, and participating businesses help fight climate change: "What hooks them is the global-warming issue," she says.

In the oxygen-deprived environment of a landfill, rotting food produces methane, a gas with 72 times the global- warming potential of carbon dioxide. Landfills are the largest human-made source of methane emissions in the United States, with a greenhouse-gas impact equal to one-fifth of that produced by the nation's coal-fired power plants.

"While we're working on getting cars off the road and shutting down coal plants, composting is the fastest, easiest, cheapest way to deal with greenhouse-gas emissions right now," says Linda Christopher, executive director of the Grassroots Recycling Network.

Compost programs don't lack for raw material: A fourth of the nation's trash is made up of "putrescibles"--food scraps, yard waste, and other biodegradable rubbish. Leaves and yard waste have been banned from landfills in 22 states, but only a handful of communities nationwide compost food scraps. Last year San Francisco supplied residences with compost bins and made it illegal to put food and yard waste in the garbage.

Recycling advocates would like to see the 3,800 U.S. facilities that compost leaves and yard debris begin to take food waste as well, but it will require costly measures to cope with odors and screen out plastic detritus like sandwich bags, latex gloves, and sporks. Once that's done, however, the worms and microorganisms can do their work, resulting in a black, nutrient-rich compost prized by farmers and gardeners. Given the demand, Christopher argues, we should start thinking of food scraps as a resource, not refuse. "When they're tossed into the landfill," she says, "they're lost to us forever." —Dashka Slater

Not a Lot of Axolotls

The axolotl's resemblance to an alien goes beyond appearance and orthography. It can regenerate lost limbs; it spends its life in water but can breathe air when it wants to; and it has survived (thus far) in a dismally polluted habitat--Mexico City's Lake Xochimilco.

The axolotl's resemblance to an alien goes beyond appearance and orthography. It can regenerate lost limbs; it spends its life in water but can breathe air when it wants to; and it has survived (thus far) in a dismally polluted habitat--Mexico City's Lake Xochimilco.

The nine-inch salamander's evolutionary quirk is that it spends its entire life in an external-gilled larval state. That suited it well in the past, but today's axolotl has to contend with wastewater from one of the world's largest cities, nonnative species that eat its offspring and food, and a persisting tradition of axolotl tamales.

Only 700 to 1,200 survive in the wild.

Mexican conservationists are trying to establish refuges to protect the axolotl and to make it a symbol for nature tourism and environmental education. For the moment, however, it's easier to find an axolotl in a pet store or on a T-shirt than in the waters of Xochimilco. —Sarah F. Kessler

Global Conspiracy

Global-warming deniers from Sarah Palin to the Saudi Arabian government had a field day in December with the release of catty and occasionally scandalous e-mails between climate researchers at the Hadley Climate Research Unit (HadCRU) at England's University of East Anglia. Phil Jones, director of the unit and author of some of the e-mails, stepped down pending an investigation. Meanwhile, deniers triumphantly cite the purloined messages as proof that global warming is a fraud.

Global-warming deniers from Sarah Palin to the Saudi Arabian government had a field day in December with the release of catty and occasionally scandalous e-mails between climate researchers at the Hadley Climate Research Unit (HadCRU) at England's University of East Anglia. Phil Jones, director of the unit and author of some of the e-mails, stepped down pending an investigation. Meanwhile, deniers triumphantly cite the purloined messages as proof that global warming is a fraud.

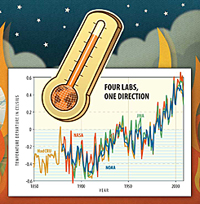

But the Hadley lab is just one of four major organizations tracking global temperatures; the others are NASA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). A global conspiracy--or just a warmer globe? —Paul Rauber

Woe Is Us: Ready, set, panic.

Hand Me a Tissue

Hand Me a Tissue

The last time the earth was menaced by ooze (The Blob, 1958), we had Steve McQueen to save us. But McQueen died in 1980, and now the blobs are not confined to celluloid. In a particularly revolting manifestation of a warming planet, the world's waterways are increasingly clogged with snotlike masses of microorganisms, living and dead.

In summertime in the Mediterranean, concentrations of "marine mucilage" stretch for hundreds of miles off the Italian coast, fouling nets, smothering fish, and nauseating swimmers. Similar conditions have been reported in the North Sea and off the coast of Australia. A 2009 study found that the outbreaks have "increased almost exponentially" in the past 20 years and linked them to the warmer, stiller waters consistent with climate change. Beyond the "ick" factor, the blobs harbor viruses and bacteria, including the deadly E. coli, in concentrations large enough to sicken bathers and force beach closures.

Mucus blobs also plague freshwater streams. The diatom Didymosphenia geminata, a.k.a. "didymo" or "rock snot," is native to North American rivers but has recently expanded its range greatly throughout the Rocky Mountain West and into Canada.

Huge colonies of these single-cell creatures attach themselves to rocks or plants on stream bottoms, covering up to 90 percent of the surface area with strands that resemble streaming toilet paper and crowding out fish, plants, and insects, not to mention would-be swimmers. —P.R.

AS THE WORLD WARMS

Quick thinking before we slowly fry

BLOW ME DOWN A blustery November weekend allowed wind farms to generate 53 percent of Spain's electricity for five hours, setting a new record for a country that gets a quarter of its power from alternative energy. Thanks to government subsidies and breezy weather, wind power has blown past other renewables in Spain, jumping from 9 percent of Spanish electricity production in the first nine months of 2009 to 14 percent in October.

MUSCLES PER GALLON As the Ford Mustang and the Chevy Camaro duke it out for the title of manliest muscle car, the Mustang has a surprising new throwdown: best fuel efficiency. The 2011 Mustang V-6 will not only boast a 305-horsepower engine--that's 95 more than the 2010 model--but also get 30 mpg on the highway. Ford claims to be the only car manufacturer offering 300 horsepower and 30 mpg in the same package, but the 304-horsepower, 29-mpg V-6 Camaro is right on its tail.

DOGHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS Not content with shedding and shoe chewing, our canine companions are out to wreck the climate as well. British architects Robert and Brenda Vale calculate that the annual ecological pawprint of a medium-size dog is twice what's required to construct a Toyota Land Cruiser and drive it 6,200 miles. Fido's carnivorous diet is to blame, which leads the Vales to suggest that we trade him in for vegetarian--and ultimately edible--pets like rabbits or chickens, or else feed him lower-impact leftovers from the table. —D.S.

ON THE ONE HAND . . .

The Montreal Protocol, which banned ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) from products like refrigerators, air conditioners, and insulating foam, is widely hailed as the most successful international environmental agreement in history. Introduced in September 1987, the protocol was eventually signed by every member of the United Nations and has succeeded in phasing out 96 percent of the ozone-zapping chemicals. While there is still a hole in the ozone layer over the South Pole, scientists expect it will close by 2050.

ON THE OTHER . . .

The ozone-safe hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) that replaced CFCs have a downside: They contribute to global warming with a vigor 4,470 times more potent than carbon dioxide's. The Montreal Protocol called for phasing them out by 2030, but climate activists say that's too long to wait. While HFCs make up 2 percent of U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions now, they could account for 9 to 19 percent of warming gases by 2050. Ozone- and greenhouse-safe substitutes are on the way: Coca-Cola has already committed to ridding its vending machines of HFCs by 2015.—D.S.

Et Tu, Exxon?

Oil-industry giant hedges its bets on climate change

Has ExxonMobil turned away from the dark side? Last December, the oil behemoth--notorious for funneling millions of dollars to climate-change skeptics--announced a $31 billion deal to buy XTO Energy, one of the largest U.S. natural gas producers. Analysts dubbed the move a hedge against climate change: Since natural gas has a smaller carbon footprint than coal or oil, it would be a major profit center if Congress enacted laws penalizing CO2 emissions.

"It doesn't prove they believe in global warming," says Joseph Romm, a climate expert who blogs for the Center for American Progress (climateprogress.org). "But given that this has been the most backward oil company in the world on the issue, one has to look at it as a climate-change play."

Or it could be a routine business decision by a company struggling to grow. Finding large new oilfields to exploit has become increasingly difficult, says energy analyst Geoffrey Styles. But the natural gas sector, with huge reserves unlocked by new technologies like hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, is booming. "Exxon probably sees this as a global opportunity it doesn't want to miss," Styles says. "If it happens to have other benefits, that's just gravy."

To realize those benefits, however, Exxon may find itself in the unfamiliar position of supporting government action to halt climate change. Although a supply glut has severely depressed natural gas prices, coal is still cheaper.

"If you want to see substantial growth in natural gas," Romm says, "you have to use it to replace coal." And the only way that would happen would be if Congress put a price on CO2.

The irony is as thick as an oil slick. Exxon has fought for years to prevent action on climate change. Now its business plan may require it.

— Andrew Leonard

Photos and illustrations, from top: Larry Strong, courtesy of Recology; Jane Burton/Bruce Coleman Inc./Alamy; Graph: Peter and Maria Hoey, graph source: Michael Schlesinger; Peter and Maria Hoey