sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - may/june 2010 - mixed media

Mixed Media | Deep Thoughts and Oddball Interpretations

Fresh, Clean, and Scarce | Earth Beat

Fresh, Clean, and Scarce

Tracking the growing global water crisis

"When the well is dry, we learn the worth of water." Benjamin Franklin's aphorism grows more apt daily. Across the globe, societies are running alarmingly short of humans' most indispensable resource: freshwater. As that occurs, humankind is polarizing into water haves and have-nots.

"When the well is dry, we learn the worth of water." Benjamin Franklin's aphorism grows more apt daily. Across the globe, societies are running alarmingly short of humans' most indispensable resource: freshwater. As that occurs, humankind is polarizing into water haves and have-nots.

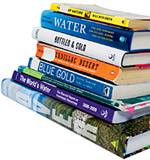

When I began researching water issues eight years ago, there were few user-friendly media resources to guide me. Now there are many. Water: H20 = Life, an engaging exhibit that ran two years ago at New York's American Museum of Natural History, has a Web site as rich as the show itself--a colorful, family- and educator-friendly gateway that covers how we use and abuse water, with videos, animation, and 150 photos.

There's no better place to learn about the tiny fraction of Earth's water that sustains civilizations than the U.S. Geological Survey's Water Science for Schools site. The USGS's authoritative Water Use in the United States page reveals that 48 percent of the country's water is withdrawn for thermoelectric power (more than the 37 percent used for irrigation) and documents the remarkable leap in national water-use efficiency since the Clean Water Act was enacted in 1972. For live stream-flow measurements, check the agency's real-time water map. Why is the USGS such a font of information on water issues? It helps that John Wesley Powell, the famed one-armed explorer of the Colorado River and a champion of Western irrigation, once led the agency.

To quickly understand the alarming transformations occurring across the U.S. landscape--such as Southwestern deserts morphing into water-sucking golf-course communities and agricultural tracts—I reach for the coffee-table-book-size aerial photographs in Alex MacLean's award-winning Over: The American Landscape at the Tipping Point (Abrams, 2008).

Comprehensive digital mapping and interactive databases of global freshwater eco-regions and wildlife species can be found at the Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Foundation's ongoing project Freshwater Ecoregions of the World. Click on any of 426 eco-regions on its map and learn all you need to know about the planet's water resources.

Another indispensible destination for anyone delving into the multifaceted world water crisis is the biennial volume The World's Water, created by the nonprofit Pacific Institute. The site's most popular features are its chronology and clickable maps of water conflicts dating back to history's first water war, in Mesopotamia 4,500 years ago between city-states Umma and Lagash.

Another indispensible destination for anyone delving into the multifaceted world water crisis is the biennial volume The World's Water, created by the nonprofit Pacific Institute. The site's most popular features are its chronology and clickable maps of water conflicts dating back to history's first water war, in Mesopotamia 4,500 years ago between city-states Umma and Lagash.

Mark Twain quipped that "whiskey is for drinking; water is for fightin' over." But are water wars inevitable? Not necessarily, suggests Oregon State University scholar Aaron Wolf, whose Transboundary Freshwater Disputes Database reveals that cooperation eventually prevails in most international water disputes.

Local water-related violence, however, has been the stuff of at least three Hollywood hits: William Wyler's The Big Country (1958), Roman Polanski's Chinatown (1974), and Steven Soderbergh's Erin Brockovich (2000). The latter two are based on real events: Los Angeles' ruthless heist of remote Owens Valley's water, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company's poisoning of town groundwater by one of its plants. L.A.'s liquid thievery is also richly narrated in Marc Reisner's beloved classic Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water (Penguin, 1993, revised edition), about the water battles that shaped the West, and in the hard-to-find four-part 1997 documentary of the same title.

The global water crisis is starting to frighten big business, whose need for reliable supplies and political stability is threatened by impending water and food shortages. Executives' concerns are reflected in the Davos World Economic Forum's new report on water security, World Economic Forum Water Initiative. Voices opposed to the global marketization of water are already galvanized by media such as Irena Salina's award-winning 2008 documentary Flow) and two book-and-movie projects: 2002's Blue Gold by Maude Barlow and Tony Clarke, and 2003's Thirst by Alan Snitow and Deborah Kaufman.

Water is growing scarce, and yet we're still polluting it? The New York Times' continuing series "Toxic Waters" reports that some 40 percent of U.S. drinking water is contaminated, sickening 20 million people each year. The "Toxic Waters" site includes many useful links, including one that lets you find out how bad your local water is. Frontline's powerful 2009 documentary Poisoned Waters details the forces degrading the country's waterways.

Don't even think that reaching for bottled water is an easy answer to water shortages. Bottled and Sold: The Story Behind Our Obsession With Bottled Water (Island Press, 2010), by MacArthur "genius grant" recipient Peter Gleick, confronts readers with questions like "If it's called 'Arctic spring water,' why is it from Florida?" Commit to staying current on water news and developments with a site like Circle of Blue or cough up just eight minutes to watch The Story of Bottled Water. —Steven Solomon

Earth Beat: Science Among Sound Bites

"Science is never-ending refinements of truth," says Stephen Schneider. "If things are very well established, that's as close to truth as we get."

"Science is never-ending refinements of truth," says Stephen Schneider. "If things are very well established, that's as close to truth as we get."

It's not often that you find a scientist willing to take off his lab coat and don boxing gloves. But climatologist Stephen Schneider, who in 1992 was awarded a MacArthur "genius grant" for his success in fostering discussion of climate issues among scientists, the public, and policymakers, is as comfortable on a freewheeling television panel as he is in the hushed halls of academia. The recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize (along with his colleagues on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Schneider authored

Science as a Contact Sport: Inside the Battle to Save Earth's Climate (National Geographic, 2009) about his four decades as a heavyweight in the debate over global warming.

Why should scientists be involved with the politics surrounding science?

Because we're not just scientists; we're human beings. If I see something that has relevance in social decision making, it's my obligation to discuss it.

After four decades of news on global warming, what's changed?

It's become a household word. The bad news is that the debate has become so ideologically polarized that we're stuck in gridlock. Since global warming is global, you have to have a large-scale cooperative solution—which starts looking like world government. Right-wing ideologues believe there is no environmental problem so bad it's worth giving up national sovereignty to an international authority. So they deny that the problem is real.

Climate historian Spencer Weart bemoans a decline in the prestige of "authoritative organizations."

It's what the radicals want. They want information to be a democracy. Opinions should be a democracy, but not information. Science is not a democracy. Quality trumps equality.

How do scientists contribute to the confusion?

We bury our leads. We lead with our caveats. That's an honest thing to do. But in a sound-bite world, when the other guys are willing to make three attacks in 20 seconds, each of which is trivial or wrong, you can't respond in 20 seconds. It's easy to attack; it takes time to defend.

In your book, you ask, "Can democracy survive complexity?" Can we avoid the pessimistic answer?

With a media that's interested in ratings instead of the truth? I doubt it.

Are environmentalists helping or hurting the debate?

By their shrillness, environmentalists harm their own credibility. I tell my environmental friends all the time, "Don't overstate. The truth is bad enough."

How should scientists operate in a sound-bite world?

I use metaphor to convey urgency and uncertainty. I ask people, "How many of you have had a house fire?" Then, "How many of you have fire insurance?" There's only a 2 percent chance your house will burn down, yet we all hedge our bets in the face of that nasty outcome. It's absurd to wait until the climate science is completely well established to act.

Does climate change have to smack people in the face to get their attention?

How did we get a Montreal Protocol to ban ozone-depleting substances? We had an ozone hole in living color on the evening news. And then people acted. Ronald Reagan signed it, over the opposition of several of his cabinet members!

Whenever there's a snowstorm, skeptics see it as proof that there's no global warming.

That's like figuring out Willie Mays's lifetime batting average by looking at how he did in two weeks in July 1958.

Is it possible for one person to change the dynamic?

Bottom-up efforts make a difference. We're talking about federal policy because we have over 300 cities and 20 states that have acted. It's taken us 20 years, but we're further ahead than when I started this.

What's your worst fear?

That we won't be lucky enough to get an emotionally tangible, media-worthy weather event like a hurricane that takes out Miami, massive fires in the West, killer heat waves, or irreversible sea-level rise soon enough to mobilize political opinion, and it'll be 25 years and by then we'll be so committed to doubling and tripling carbon dioxide that we won't be able to reverse it.

What's your greatest hope?

That even though scientists bury their leads, we listen to the ends of their sentences and say, "We've got to fix this problem, and we can."

What's your environmental vice?

South Australian Shiraz. There's a lot of carbon embedded in that.

—interview by Reed McManus

Photos, from top: Scott Suchman (2); Anne Hamersky