the john muir exhibit - life - bailey millard

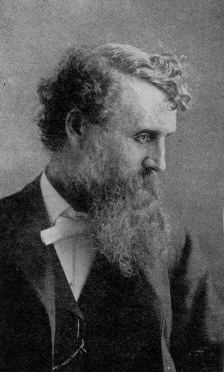

John Muir

By Bailey Millard

John Muir, naturalist, geologist and explorer, was as much a poet as

any of these, and his work refutes the idea harbored by the spiritual mind

that a scientist must needs be an arid plodding dissector of nature and

a cold, passionless investigator of her secrets. Muir flings open to the

imagination the boundless field of natural life, and as we read his

books there is revealed to us the vision of peak and canyon, of tree and flower.

We are impressed, most of all, by the authenticity of his report which could come only from exact knowledge such as he acquired during a long life of close and sympathetic research.

Muir, who lived near Martinez, not far from the upper bay waters, was much loved by Californians. He spent most of his life in the Golden State and did all his most famous work here. He was born in 1838 and died in 1914. His boyhood days were spent in the middle west. While still only a youth he wandered away from his Wisconsin home and came to California, poor, without friends but with such zeal for knowledge of nature's handiwork as was bound to eventuate in the making of a great naturalist, perhaps the greatest this country ever has known. He arrived in San Francisco in the early '70s and struck out immediately for mountains on foot through the San Joaquin Valley. He studied the Sierras and wrote many interesting articles and books on them. He the first man to evolve the theory that the Yosemite Valley was scooped out by glacial erosion, and he proved it in the face of all the wise men who were so fond of accounting for it by cataclysm. He gave the world first accurate scientific knowledge of the California big trees and found many hitherto unknown glaciers in the Sierras.

John Muir had an affinity for solitude and silence. The frankness, the simplicity, the carelessness and the extreme sensitiveness of the man who lives dose to nature were all his. So receptive was his mind that had some remarkable telepathic experiences.

"One day," he related to me, "I was sitting on top of the North Dome of Yosemite when there came to me a strong flash of intelligence concerning Prof. J. D. Butler, my old Latin teacher of the University of Wisconsin. I had not heard from Butler for years, but I was now persuaded that he was just entering the valley, which was the fact."

Butler was thinking of Muir and hoping to find him in the valley, and Muir's sensitive, impressible and highly receptive mind caught the message like the antennae of a radio.

"I sprang up," said Muir, "and started toward the hotel, four or five miles distant, but it came to me that it would be impossible to get there, until late, and not wishing to disturb my friend, I waited until morning when I went down, found Butler's name on the hotel register, and was told he had gone to Vernal Falls. I followed up the trail and met him top of Liberty Gap."

Muir's books on "The National Parks" contained wonderful descriptions of the canyons and forests. Although he wrote very slowly his language did not seem to lack spontaneity. As a rule he left nothing of value to be said about any subject that he covered. Read his chapter on the Yellowstone and you cannot fail to feel the finality of it. For to describe the Yellowstone after Muir would be like trying to write a new "Inland Voyage" after Stevenson.

"I write and rewrite," he said to me once, "and make terrible work of it. I always like to consider the infinite possibilities. So I turn my material this way and that and brood over it like a setting hen. Some- times it will take me six weeks to write an ordinary magazine article of seven or eight thousand words." To him writing was boresome. He preferred trail climbing. ""Up there among the glaciers," he said, "one gets a lot of light on how God is making the worlds, how the cosmos is growing. Beauty is being made there. The snowflakes are being compacted, the atoms of the rocks are being united into a solid grand army, and marching to music."

John Muir has been called the Skyland Philosopher, and the chief element of his philosophy, like that of most great and true men, was simplicity. With this was coupled a fine, fragrant faith. Imagine a man setting out to scale a mountain or traverse a great glacier and to remain for weeks in a practically unknown region with no other camp equipment but a pocket knife, a tin cup and the clothes he stood in, and no other provision than a bag of bread and a little tea! And yet Muir did this time and again, and never felt that he was tempting the fates; and always, even after he had been given up as lost, he would return to his home,

weary perhaps, but little the worse for adventures that would have killed an ordinary being. When he read of the elaborate preparations of Abruzzi and other mountain climbers he laughed.

"Why don't they go up in Pullman cars?" he used to say.

Muir traveled much. He went to Florida, to Cuba, to Alaska, to Mexico, to Australia, to Siberia, to India - all over the world - in the pursuit of his studies as a naturalist. He compared the giant eucalyptus trees of Australia with the Californian big trees and found the former much smaller, though they had been reputed to be of greater size.

In his sixty-fifth year he went to India, and from Ceylon he sent me a letter saying he had climbed some of the tall peaks of the Himalayas. The experience was interesting, but no more so than what he had enjoyed in the Sierras. He went to Alaska in the '80s and discovered the great glacier that bears his name. In 1899 he went again to Alaska with the Harriman expedition, with John Burroughs, Charles Keeler and other naturalists. One morning Burroughs protruded his head into Muir's stateroom on the steamer and twitted him for not having been up on deck twenty minutes before to enjoy the beautiful scenery of the Taku Inlet, which Burroughs had viewed for the first time.

"John Burroughs," returned Muir, "you should have been up here twenty years ago instead of sitting about in your cabin on the Hudson."

Both these men were great naturalists, but Muir's experience was of a far wider nature than that of Burroughs. Muir accompanied President Roosevelt to the Yosemite as guide in 1903. It was a boresome affair to the great naturalist, who did not want to go, as he was at work on an important article in his Martinez study when he received the invitation to which many another man would hare delighted to respond.

"But my dear Muir," said a friend who happened in just as he was about to send back his regrets, "a man must always accept the president's invitation.

"Must he?" said Muir dubiously. Yes; it's like the command of a king to his subject."

To the liberty - loving old mountaineer this was no sort of appeaL How he at last persuaded himself to go at the bidding of the chief magistrate was curiously characteristic of the man.

"Well," he argued against his inclination, "I suppose I shouldn't refuse just because he happens to be president."

Having the privilege of inviting a friend to accompany him, he asked me to go

along, but a press of editorial work kept me in San Francisco. However, I guided

him through the streets of the city, in which he was far more likely to get

lost than in any mountain wilderness, and across the bay to Oakland, where

I saw him safely aboard the president's private car. It was night and Mr. Roosevelt

had not yet come down to the train, so, Muir, instead of waiting up for him,

went directly to bed! Now this may seem a bit strange and perhaps poseful,

hut if you had known Muir you would know that it was the most natural and

most likely thing that he would have done; and as for pose, he was simply incapable

of it.

One day Mrs. Muir caught her husband in the act of throwing a roll of something into the fire, "What's that?" she asked, knowing him of old as likely to commit an overt act in the destruction of what he called treasured trash.

"Nothing but that old piece of parchment, I don't want it lumbering up my drawer."

Mrs. Muir seized the parchment and unrolled it.

"Why, John!" she exclaimed. "This is your bachelor's degree from Harvard."

"I thought so," said he. "Well take it away, if you prize it so highly."

When asked why he refused professorships in colleges he said" "Oh, there are already too many men teaching things they have got out of books. What are needed are original investigators to write new books, and if I live I'm going to study and not teach."

He had his own ideas of health. Once when he bad very severe cough he nearly drove his wife to despair by announcing that he was going up in the glaciers to make further explorations.

"But you are ill, John," Mrs. Muir remonstrated. "It will kill you. You mustn't

dream of going. You'll never come back alive."

"Yes I will!" he declared stoutly, choking back his cough. "For a disease like bronchitis there's nothing in the' world like sleeping on a glacier." So he went and was cured.

He laughed at the friends of Emerson who visited the Yosemite in his company in the '70s because they would not let him camp out for the night, but must take him off to a hotel. He accused them of having the house habit. For himself he did not intend to suffer from indoor complaints. He lived for seventy-six years. Of all my friends that have passed away it is hardest to think of him as dead. Even now it seems strange for one who knew him so well to be writing in the past tense of this restless, eager, always essentially alive man who spent so much of his time in strenuous tramps among the forests and mountains, and it is particularly strange because he kept up his wild quest for new and strange places and objects to such an advanced age that one came to think of him as an immortal and eternal seeker out of Nature's hidden shrine. And indeed, it is easy to fancy him at this moment, peering into some remote and secret fold of the Sierras, into some inaccessible Arizonian canyon or into some abysmal Alaskan crevasse, or lifting himself in triumph upon the summit of some Himalayan or Andean peak whose snows never have received the impress of man's footprints.

Excerpted from History of the San Francisco Bay Region, (San Francisco, The American Historical Society, Inc., 1924). Copyrights for works first published before 1964, and first published in the US, that were not registered and renewed in a timely manner, have now expired into the public domain. A search conducted on 9-22-03 of the U.S. Copyright Office Catalog of Copyright Entries for 1951, 1952, and 1953 failed to locate a copyright renewal for this work.

Life and Contributions of John Muir

Home

| Alphabetical Index

| What's New