the john muir exhibit - people - ryozo azuma by william and maymie kimes - famous people influenced by john muir - john muir exhibit

Ryozo Azuma, the John Muir of Japan

by William and Maymie Kimes

Sierra, Vol 64, No. 2, July/August, 1979

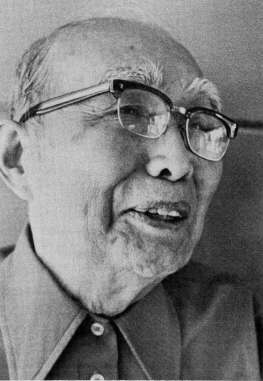

At 90, Ryozo Azuma, Honorary Life Member of the Sierra Club,

Recalls a Special Meeting with John Muir

Reprinted by permission.

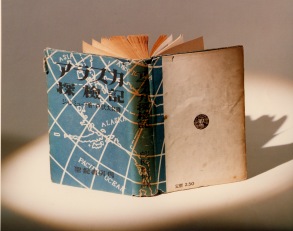

In the spring of 1973, while we were doing research for a bibliography of John Muir’s writings, our attention was drawn to a letter by a Mr. Ishigaki to the Muir family, requesting permission to translate Muir’s writings into Japanese. A postscript states “Travels in Alaska was translated and published in Japan in 1942.” This was astonishing news, our first inkling that a Japanese translation of Muir’s writing existed! Excited, we determined to locate the book, which would certainly be a unique entry for the bibliography. In our search we found that Ryozo Azuma of Tokyo was the author of a current biography of John Muir published in Japanese. Surmising that if anyone would know of the translation, surely he would, we sent our first inquiry to him. We were delighted by his reply: “It is my pleasure to tell you that I loaned my Travels in Alaska to a professor at Tokyo University who in turn loaned it to a student, Mr. Taro Tobuse who, inspired immensely by the Alaskan expedition made by John Muir, ventured to translate it into Japanese. It was published by a small publisher in 1942. It would be difficult to find it even in old book stores at the present, although I myself still keep it in my library.” So we had stumbled upon a fellow Muir enthusiast in Japan, though we had no idea then how strongly Muir had figured in Ryozo Azuma’s life. Our correspondence was to initiate a long and rewarding friendship.

Our first letter from Azuma also revealed that he would be visiting the national parks of Alaska and the West Coast, sponsored by the National Park Association of Japan, and that he would be accompanied by his wife in celebration of their 55th wedding anniversary. Although we had planned an Alaska trip ourselves, we quickly postponed our departure in order to meet this distinguished man when his group arrived in Yosemite, only an hour’s distance from our home. In a letter mailed just before Azuma’s departure from Tokyo, he wrote, “My heart is already in the wilds of Alaska and Yosemite, dreaming the happy meeting with you who mutually pay a hearty admiration to that great naturalist John Muir.” And indeed it was a happy meeting. With our common interests, it seemed as if we had known each other for years.

Ryozo Azuma was a small, wiry man with an alert and energetic manner that belied his 84 years. He recounted some of his mountaineering feats, telling us he had climbed more than 140 peaks in the western part of our continent. He had made nine trips to Alaska and, most amazing of all, in his youth he had known John Muir! The evening was all too short, and we didn’t get the complete story of his adventuresome life until two years later, when he and his wife, Tsuya, returned to the United States to visit their daughter, and agreed to be our guests for several days.

One late summer afternoon, as the sun descended behind the pine-crested ridge overlooking our home in the Mariposa foothills, Ryozo enthusiastically related the most important incident of his long and fruitful

life -- his meeting John Muir in May 1914. With much feeling, he said, “that thankful opportunity, visiting with him in Martinez, was so poignant and significant that the deep spiritual influence I had from John Muir has dramatically and decisively directed the way for my whole life.” At the age of 20, Ryozo had come to Tacoma to attend Puget Sound College, a mission school, having been encouraged to do so by an American professor in Kyoto. Ryozo soon joined some young men of the YMCA who planned to hike all the way around Mount Rainier and to finish their expedition with a climb to its summit. As was customary in an ascent, they spent their first night part way up the mountain in a cave named Camp Muir. Being a curious fellow, Ryozo inquired of their Swiss guide, “Who is Muir, that a camp should be named for him?” The guide had conducted Muir’s party to the summit in 1888, and his interest in Muir’s achievements was contagious, leading Ryozo subsequently to “read all books of Muir with burning enthusiasm one after another.” While he attended college during the following five years, he became an avid mountain climber--this stimulated his fascination not only with Muir’s writing, but with Muir himself.

Ryozo related, “It was in the spring of 1914; I ventured to send a letter prudently to Muir, asking him if I could be allowed to visit his homestead at Martinez. Promptly on receipt of a cordial reply from my admiring great man of many years, I took a train in high spirit from Seattle to San Francisco. I was extremely surprised to find a young man from the Sierra Club waiting when the train reached Frisco. I was tremendously moved to know that the kind-hearted Muir had arranged to take me to Martinez easily. After taking a wagon ride for about six hours from Oakland with newly found friend, we reached Muir mansion surrounded by rich orchard at twilight. Muir himself soon came out to the porch with familiar heavily whiskered face in smile. I just stood in a daze before my long-revered figure for little while in excess of joyful emotion. Muir stretched his big hand for greeting me, but I simply knelt humbly under him in moving tear, as if having audience by king or pope. Muir was an old man of 75 then; I was only a young fellow of 24. Muir was world renowned personage, and I was just scanty poor college boy--a great many miles difference between the two as heaven and earth.”

“However, Muir seemed taken with certain interest in meeting me, probably because I was first and only Japanese nature-lover ever paid a private call. Although I stayed only two days in Muir mansion, I was exceedingly happy and deeply moved in various ways. I was much excited when he generously permitted me to take a look at his study upstairs where he was busily working on his last manuscript,

Travels in Alaska. I was amazed in seeing a remarkable landscape painting of Yosemite Valley, also a portrait of Mr. Emerson in frame, and a big-size Bible on his large writing desk. All those dear memories are still fresh in my mind. I never forget, though more than 60 years has elapsed.”

When we asked Ryozo what happened the next day, he said that a Mr. Hooper came to dinner, the captain of a revenue cutter who was a long-time friend of Muir’s from the cruise of the Corwin. The Captain expressed concern that he must depart for the Arctic the next day but still had no cabin boy, and Muir promptly remarked, “Take Ryozo! He should see Alaska.” This suggestion, so startling at first, culminated in Ryozo’s accompanying Captain Hooper to the Arctic. Azuma recalled that the voyage was very difficult, especially crossing the Bering Sea, full of floating ice; however, they finally reached Point Barrow in late July of 1915. Unfortunately, they delayed their departure too long; suddenly the vessel was iced in. Captain Hooper kindly arranged for Ryozo to stay at a Presbyterian Mission, where he made the acquaintance of friendly Eskimos. Their language he picked up easily, he confided, since it consisted mainly of names of objects. After he had spent a pleasant winter in the village, the Eskimos invited him to join their hunting party of about 60 men, women and children. He accepted, and they skirted the coast from Point Barrow well into Canada. Azuma recalled that it had been an exciting and inspiring adventure, but a very long and hazardous one that lasted two years and seven months. At the mouth of the Mackenzie River he left the main part with two young Eskimos, and headed into the interior for the Yukon, finally reaching Tacoma in 1919. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer published a series of articles on his adventures, appropriately naming him Mr. Eskimo.

Fortune continued to favor Azuma --- he found employment with the Japanese government in the promotion of trade between Japan and the western countries, and this official position enabled him not only to visit every state in the United States, but to make frequent trips to Canada, South America and some European countries.

Finally, in 1934, he was called home to Japan, where he eventually became an adviser to the military on food supply. Sometime before the end of the war, his superior objected to the posters picturing mountains of Canada and the United States that always decorated Azuma’s office, declaring them traitorous. With angry impatience, and in spite of the remonstrances of his friends, Azuma resigned his job. He then made a decision that was to be a milestone in his life: to devote his time to writing “in the hope to give the people of Japan a true knowledge about America and their cultural life--to show the good and noble side of the American people!”

This necessitated his living on savings and on what he could earn from lecturing. Our ambassador of goodwill worked prodigiously, authoring more than two dozen volumes, including America’s Holidays--Their Origin and History, the Story of the States of America and The United States Presidents and Their Wives. He has also written extensively about the national parks and wilderness of Canada and the United States, and their explorers. Azuma has the distinction of being the first person to write about John Muir in Japanese, in a series of articles that appeared in the publication of the National Park Association of Japan. They created so much interest the association commissioned Azuma to write a biography. The result was The Life of John Muir, Father of Nature Conservation, published in 1973. By this time, Japanese conservationists as well as leaders of our national parks were identifying him as the John Muir of Japan, not only for his writing, which is invaluable, or for his record of difficult ascents, which is impressive, but also for the significant direction he has given over the years as adviser to the National Park Association of Japan.

During the last of the Azumas’ visits with us, we accompanied them on their sayonara pilgrimage to Yosemite. Park Superintendent, Leslie P. Arnberger honored them at a tea to which he invited all his employees, an audience Azuma captivated by relating his experiences with both pathos and humor. The climax of his return to his “second homeland,” as he often called it, was his final visit to Muir’s “mansion” at the National Historic Site in Martinez. For the occasion, Superintendent Doris Osmundson staged a special luncheon with an array of important guests, including three of John Muir’s grandchildren. Again, Azuma charmed the guests, relating in touching detail his meeting with Muir and the far reaching horizons it opened for him.

Immediately upon Azuma’s return to Japan, he was asked to attend the Annual General Assembly of Nature Conservation, where he was awarded an “Official Commendation in Acknowledgment of Meritorious Service” by the Agency of Environment, which read: “You have contributed a distinguished service for many years...infusing the concept of....Nature Conservation by constantly introducing the National Park System of its original Senior Country, the United States.”

It was Marshall Kuhn’s introduction to Azuma at the luncheon in Martinez that prompted Kuhn (the late founder of the Sierra Club’s History Committee) to suggest that the club honor Muir’s remarkable disciple. In 1977, the Club’s board of directors presented a life membership to Ryozo Azuma in recognition of his contributions to conservation, especially his book The Life of John Muir, stating: “In coming years Japanese and American conservationists will be cooperating on many projects. Your book helps to make possible common ground for this work.” We can all be grateful that Azuma not only met John Muir, but caught his vision and transmitted his legacy to Japan. In honoring Ryozo Azuma, the Sierra Club indeed brings international honor to its members!

Source: Ryozo Azuma, the John Muir of Japan,

by William and Maymie Kimes, Sierra, Vol 64, No. 2, July/August, 1979, pp. 42-44. Color photo was not part of the original article.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to the Kimes family for permission to reprint this article; Gene Rose for permission to reproduce his photo of Ryozo Azuma; Jill Harcke for the scan of the Kimes' photo of the Japanese version of Travels in Alaska; the National Park Service for the photo of Azuma at the John Muir National Historic Site; and to Margaret Stuhr for re-typing this article for the John Muir Exhibit.