the john muir exhibit - writings - the_story_of_my_boyhood_and_youth - chapter 7

The Story of My Boyhood and Youth

by John Muir

Chapter VII

Knowledge and Inventions

I LEARNED

arithmetic in Scotland without understanding any of it, though

I had the rules by heart. But when I was about fifteen or sixteen years

of age, I began to grow hungry for real knowledge, and persuaded father,

who was willing enough to have me study provided my farm work was kept

up, to buy me a higher arithmetic. Beginning at the beginning, in one summer

I easily finished it without assistance in the short intervals between

the end of dinner and the afternoon start for the harvest-and-hay-fields,

accomplishing more without a teacher in a few scraps of time than in years

in school before my mind was ready for such work. Then in succession I

took up algebra, geometry, and trigonometry and made some little progress

in each, and reviewed grammar. I was fond of reading, but father had brought

only a few religious books from Scotland. Fortunately, several of our neighbors

had brought a dozen or two of all sorts of books, which I borrowed and

read, keeping all of them except the religious ones carefully hidden from

father's eye. Among these were Scott's novels, which, like all

other novels, were strictly forbidden, but devoured with glorious pleasure

in secret. Father was easily persuaded to buy Josephus's "Wars of

the Jews," and D'Aubigné's "History of the Reformation,"

and I tried hard to get him to buy Plutarch's Lives, which, as I told him,

everybody, even religious people, praised as a grand good book; but he

would have nothing to do with the old pagan until the graham bread and

anti-flesh doctrines came suddenly into our backwoods neighborhood, making

a stir something like phrenology and spirit-rappings, which were as mysterious

in their attacks as influenza. He then thought it possible that Plutarch

might be turned to account on the food question by revealing what those

old Greeks and Romans ate to make them strong; and so at last we gained

our glorious Plutarch. Dick's "Christian Philosopher," which

I borrowed from a neighbor, I thought I might venture to read in the open,

trusting that the word "Christian" would be proof against its

cautious condemnation. But father balked at the word "Philosopher,"

and quoted from the Bible a verse which spoke of "philosophy falsely

so-called." I then ventured to speak in defense of the book, arguing

that we could not do without at least a little of the most useful kinds

of philosophy.

"Yes, we can," he said with enthusiasm, "the Bible is

the only book human beings can possibly require throughout all the journey

from earth to heaven."

"But how," I contended, "can we find the way to heaven

without the Bible, and how after we grow old can we read the Bible without

a little helpful science? Just think, father, you cannot read your Bible

without spectacles, and millions of others are in the same fix; and spectacles

cannot be made without some knowledge of the science of optics."

"Oh!" he replied, perceiving the drift of the argument, "there

will always be plenty of worldly people to make spectacles."

To this I stubbornly replied with a quotation from the Bible with reference

to the time coming when "all shall know the Lord from the least even

to the greatest," and then who will make the spectacles? But he still

objected to my reading that book, called me a contumacious quibbler too

fond of disputation, and ordered me to return it to the accommodating owner.

I managed, however, to read it later.

On the food question father insisted that those who argued for a vegetable

diet were in the right, because our teeth showed plainly that they were

made with reference to fruit and grain and not for flesh like those of dogs

and wolves and tigers. He therefore promptly adopted a vegetable

diet and requested mother to make the bread from graham flour instead of

bolted flour. Mother put both kinds on the table, and meat also, to let

all the family take their choice, and while father was insisting on the

foolishness of eating flesh, I came to her help by calling father's attention

to the passage in the Bible which told the story of Elijah the prophet

who, when he was pursued by enemies who wanted to take his life, was hidden

by the Lord by the brook Cherith, and fed by ravens; and surely the Lord

knew what was good to eat, whether bread or meat. And on what, I asked,

did the Lord feed Elijah? On vegetables or graham bread? No, he directed

the ravens to feed his prophet on flesh. The Bible being the sole rule,

father at once acknowledged that he was mistaken. The Lord never would

have sent flesh to Elijah by the ravens if graham bread were better.

I remember as a great and sudden discovery that the poetry of the Bible,

Shakespeare, and Milton was a source of inspiring, exhilarating, uplifting

pleasure; and I became anxious to know all the poets, and saved up small

sums to buy as many of their books as possible. Within three or four years

I was the proud possessor of parts of Shakespeare's, Milton's, Cowper's,

Henry Kirke White's, Campbell's, and Akenside's works, and quite

a number of others seldom read nowadays. I think it was in my fifteenth

year that I began to relish good literature with enthusiasm, and smack

my lips over favorite lines, but there was desperately little time for

reading, even in the winter evenings--only a few stolen minutes now and

then. Father's strict rule was, straight to bed immediately after family

worship, which in winter was usually over by eight o'clock. I was in the

habit of lingering in the kitchen with a book and candle after the rest

of the family had retired, and considered myself fortunate if I got five

minutes' reading before father noticed the light and ordered me to bed;

an order that of course I immediately obeyed. But night after night I tried

to steal minutes in the same lingering way, and how keenly precious those

minutes were, few nowadays can know. Father failed perhaps two or three

times in a whole winter to notice my light for nearly ten minutes, magnificent

golden blocks of time, long to be remembered like holidays or geological

periods. One evening when I was reading Church history father was particularly

irritable, and called out with hope-killing emphasis, "John, go

to bed! Must I give you a separate order every night to get you to

go to bed? Now, I will have no irregularity in the family; you

must go when the rest go, and without my having to tell you."

Then, as an afterthought, as if judging that his words and tone of voice

were too severe for so pardonable an offense as reading a religious book,

he unwarily added: "If you will read, get up in the morning

and read. You may get up in the morning as early as you like."

That night I went to bed wishing with all my heart and soul that somebody

or something might call me out of sleep to avail myself of this wonderful

indulgence; and next morning to my joyful surprise I awoke before father

called me. A boy sleeps soundly after working all day in the snowy woods,

but that frosty morning I sprang out of bed as if called by a trumpet blast,

rushed downstairs, scarce feeling my chilblains, enormously eager to see

how much time I had won; and when I held up my candle to a little clock

that stood on a bracket in the kitchen I found that it was only one o'clock.

I had gained five hours, almost half a day! "Five hours to myself!"

I said, "five huge, solid hours!" I can hardly think of any other

event in my life, any discovery I ever made that gave birth to joy so transportingly

glorious as the possession of these five frosty hours.

In the glad, tumultuous excitement of so much suddenly acquired time-wealth,

I hardly knew what to do with it. I first thought of going on with my reading,

but the zero weather would make a fire necessary, and it occurred to me

that father might object to the cost of fire-wood that took time to chop.

Therefore, I prudently decided to go down cellar, and begin work on a model

of a self-setting sawmill I had invented. Next morning I managed to get

up at the same gloriously early hour, and though the temperature of the

cellar was a little below the freezing point, and my light was only a tallow

candle, the mill work went joyfully on. There were a few tools in a corner

of the cellar--a vise, files, a hammer, chisels, etc., that father had brought

from Scotland, but no saw excepting a coarse crooked one that was unfit

for sawing dry hickory or oak. So I made a fine-tooth saw suitable for

my work out of a strip of steel that had formed part of an old-fashioned

corset, that cut the hardest wood smoothly. I also made my own bradawls,

punches, and a pair of compasses, out of wire and old files.

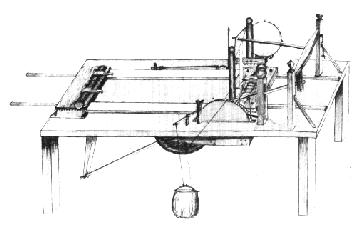

SELF-SETTING SAWMILL

Model built in cellar

My workshop was immediately under father's bed, and the filing and tapping

in making cogwheels, journals, cams, etc., must, no doubt, have annoyed

him, but with the permission he

had granted in his mind, and doubtless hoping that I would soon tire

of getting up at one o'clock, he impatiently waited about two weeks before

saying a word. I did not vary more than five minutes from one o'clock all

winter, nor did I feel any bad effects whatever, nor did I think at all

about the subject as to whether so little sleep might be in any way injurious;

it was a grand triumph of will-power over cold and common comfort and work-weariness

in abruptly cutting down my ten hours' allowance of sleep to five. I simply

felt that I was rich beyond anything I could have dreamed of or hoped for.

I was far more than happy. Like Tam o'Shanter I was glorious," O'er

a' the ills o' life victorious."

Father, as was customary in Scotland, gave thanks and asked a blessing

before meals, not merely as a matter of form and decent Christian manners,

for he regarded food as a gift derived directly from the hands of the Father

in heaven. Therefore every meal to him was a sacrament requiring conduct

and attitude of mind not unlike that befitting the Lord's Supper. No idle

word was allowed to be spoken at our table, much less any laughing or fun

or story-telling. When we were at the breakfast-table, about two weeks

after the great golden time-discovery, father cleared his throat preliminary,

as we all knew, to saying something considered important. I

feared that it was to be on the subject of my early rising, and dreaded

the withdrawal of the permission he had granted on account of the noise

I made, but still hoping that, as he had given has word that I might get

up as early as I wished, he would as a Scotchman stand to it, even though

it was given in an unguarded moment and taken in a sense unreasonably far-reaching.

The solemn sacramental silence was broken by the dreaded question:--

"John, what time is it when you get up in the morning? "

"About one o'clock," I replied in a low, meek, guilty tone

of voice.

"And what kind of a time is that, getting up in the middle of the

night and disturbing the whole family? "

I simply reminded him of the permission he had freely granted me to

get up as early as I wished.

"I know it," he said, in an almost agonized tone of

voice, "I know I gave you that miserable permission, but I

never imagined that you would get up in the middle of the night."

To this I cautiously made no reply, but continued to listen for the

heavenly one-o'clock call, and it never failed.

After completing my self-setting sawmill I dammed one of the streams

in the meadow and put the mill in operation. This invention was speedily

followed by a lot of others--water-wheels, curious doorlocks and latches,

thermometers, hygrometers, pyrometers, clocks, a barometer, an automatic

contrivance for feeding the horses at any required hour, a lamp-lighter

and fire-lighter, an early-or-late-rising machine, and so forth.

|

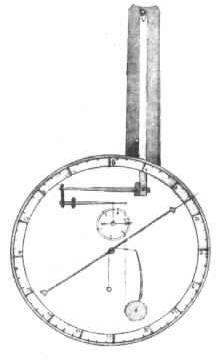

THERMOMETER

|

BAROMETER

Invented by the author in his boyhood

|

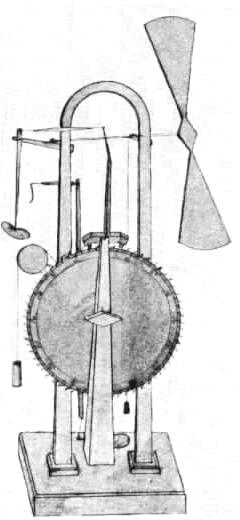

After the sawmill was proved and discharged from my mind, I happened

to think it would be a fine thing to make a timekeeper which would tell

the day of the week and the day of the month, as well as strike like a

common clock and point out the hours; also to have an attachment whereby

it could be connected with a bedstead to set me on my feet at any hour

in the morning; also to start fires, light lamps, etc. I had learned the

time laws of the pendulum from a book, but with this exception I knew nothing

of timekeepers, for I had never seen the inside of any sort of clock or

watch. After long brooding, the novel clock was at length completed in

my mind, and was tried and found to be durable and to work well and look

well before I had begun to build it in wood. I carried small parts of it

in my pocket to whittle at when I was out at work on the farm

using every spare or stolen moment within reach without father's knowing

anything about it. In the middle of summer, when harvesting was in progress,

the novel time-machine was nearly completed. It was hidden upstairs in

a spare bedroom where some tools were kept. I did the making and mending

on the farm, but one day at noon, when I happened to be away, father went

upstairs for a hammer or something and discovered the mysterious machine

back of the bedstead. My sister Margaret saw him on his knees examining

it, and at the first opportunity whispered in my ear, "John, fayther

saw that thing you're making upstairs." None of the family knew what

I was doing, but they knew very well that all such work was frowned on

by father, and kindly warned me of any danger that threatened my plans.

The fine invention seemed doomed to destruction before its time-ticking

commenced, though I thought it handsome, had so long carried it in my mind,

and like the nest of Burns's wee mousie it had cost me mony a weary whittling

nibble. When we were at dinner several days after the sad discovery, father

began to clear his throat to speak, and I feared the doom of martyrdom

was about to be pronounced on my grand clock.

"John," he inquired, "what is that thing you are making

upstairs?"

I replied in desperation that I did n't know what to call it.

"What! You mean to say you don't know what you are trying to do?"

"Oh, yes," I said, "I know very well what I am doing."

"What, then, is the thing for?"

"It's for a lot of things," I replied, "but getting;

people up early in the morning is one of the main things it is intended

for; therefore it might perhaps be called an early-rising machine."

After getting up so extravagantly early all the last memorable winter,

to make a machine for getting up perhaps still earlier seemed so ridiculous

that he very nearly laughed. But after controlling himself and getting

command of a sufficiently solemn face and voice he said severely, "Do

you not think it is very wrong to waste your time on such nonsense?"

"No," I said meekly, "I don't think I'm doing any wrong."

"Well," he replied, "I assure you I do; and if you were

only half as zealous in the study of religion as you are in contriving

and whittling these useless, nonsensical things, it would be infinitely

better for you. I want you to be like Paul, who said that he desired to

know nothing among men but Christ and Him crucified."

To this I made no reply, gloomily believing my fine machine

was to be burned, but still taking what comfort I could in realizing that

anyhow I had enjoyed inventing and making it.

After a few days, finding that nothing more was to be said, and that

father after all had not had the heart to destroy it, all necessity for

secrecy being ended, I finished it in the half-hours that we had at noon

and set it in the parlor between two chairs, hung moraine boulders that

had come from the direction of Lake Superior on it for weights, and set

it running. We were then hauling grain into the barn. Father at this period

devoted himself entirely to the Bible and did no farm work whatever. The

clock had a good loud tick, and when he heard it strike, one of my sisters

told me that he left his study, went to the parlor, got down on his knees

and carefully examined the machinery, which was all in plain sight, not

being enclosed in a case. This he did repeatedly, and evidently seemed

a little proud of my ability to invent and whittle such a thing, though

careful to give no encouragement for anything more of the kind in future.

But somehow it seemed impossible to stop. Inventing and whittling faster

than ever, I made another hickory clock, shaped like a scythe to symbolize

the scythe of Father Time. The pendulum is a bunch of arrows symbolizing

the flight of time. It hangs on a leafless mossy oak snag showing

the effect of time, and on the snath is written, "All flesh is grass."

This, especially the inscription, rather pleased father, and, of course,

mother and all my sisters and brothers admired it. Like the first it indicates

the days of the week and month, starts fires and beds at any given hour

and minute, and, though made more than fifty years ago, is still a good

timekeeper.

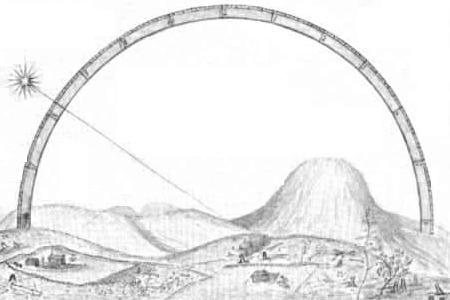

My mind still running on clocks, I invented a big one like a town clock

with four dials, with the time-figures so large they could be read by all

our immediate neighbors as well as ourselves when at work in the fields,

and on the side next the house the days of the week and month were indicated.

It was to be placed on the peak of the barn roof. But just as it was all

but finished, father stopped me, saying that it would bring too many people

around the barn. I then asked permission to put it on the top of a black-oak

tree near the house. Studying the larger main branches, I thought I could

secure a sufficiently rigid foundation for it, while the trimmed sprays

and leaves would conceal the angles of the cabin required to shelter the

works from the weather, and the two-second pendulum, fourteen feet long,

could be snugly encased on the side of the trunk. Nothing about the

grand, useful timekeeper, I argued, would disfigure the tree, for it would

look something like a big hawk's nest. "But that," he objected,

"would draw still bigger bothersome trampling crowds about the place,

for who ever heard of anything so queer as a big clock on the top of a

tree?" So I had to lay aside its big wheels and cams and rest content

with the pleasure of inventing it, and looking at it in my mind and listening

to the deep solemn throbbing of its long two-second pendulum with its two

old axes back to back for the bob.

CLOCK. THE STAR HAND RISING AND SETTING WITH THE SUN ALL THE YEAR

Invented by the author in his boyhood

One of my inventions was a large thermometer made of an iron rod, about

three feet long and five eighths of an inch in diameter, that had formed

part of a wagon-box. The expansion and contraction of this rod was multiplied

by a series of levers made of strips of hoop iron. The pressure of the

rod against the levers was kept constant by a small counterweight, so that

the slightest change in the length of the rod was instantly shown on a

dial about three feet wide multiplied about thirty-two thousand times.

The zero-point was gained by packing the rod in wet snow. The scale was

so large that the big black hand on the white-painted dial could be seen

distinctly and the temperature read while we were ploughing in the field

below the house. The extremes of heat and cold

caused the hand to make several revolutions. The number of these revolutions

was indicated on a small dial marked on the larger one. This thermometer

was fastened on the side of the house, and was so sensitive that when any

one approached it within four or five feet the heat radiated from the observer's

body caused the hand of the dial to move so fast that the motion was plainly

visible, and when he stepped back, the hand moved slowly back to its normal

position. It was regarded as a great wonder by the neighbors and even by

my own all-Bible father.

Boys are fond of the books of travelers, and I remember that one day,

after I had been reading Mungo Park's travels in Africa, mother said: "Weel,

John, maybe you will travel like Park and Humboldt some day." Father

over-heard her and cried out in solemn deprecation, "Oh, Anne! dinna

put sic notions in the laddie's heed." But at this time there was

precious little need of such prayers. My brothers left the farm when they

came of age, but I stayed a year longer, loath to leave home. Mother hoped

I might be a minister some day; my sisters that I would be a great inventor.

I often thought I should like to be a physician, but I saw no way of making

money and getting the necessary education, excepting as an inventor. So,

as a beginning, I decided to try to get into a big shop or factory

and live awhile among machines. But I was naturally extremely shy and had

been taught to have a poor opinion of myself, as of no account, though

all our neighbors encouragingly called me a genius, sure to rise in the

world. When I was talking over plans one day with a friendly neighbor,

he said: "Now, John, if you wish to get into a machine-shop, just

take some of your inventions to the State Fair, and you may be sure that

as soon as they are seen they will open the door of any shop in the country

for you. You will be welcomed everywhere." And when I doubtingly asked

if people would care to look at things made of wood, he said, "Made

of wood! Made of wood! What does it matter what they're made of when they

are so out-and-out original. There's nothing else like them in the world.

That is what will attract attention, and besides they're mighty handsome

things anyway to come from the backwoods." So I was encouraged to

leave home and go at his direction to the State Fair when it was being

held in Madison.

[

Back to Chapter 6

|

Forward to Chapter 8

|

Table of Contents

]