|

|

Despite safe and proven alternatives, Pentagon to burn chemical weapons

by Tom Valtin

|

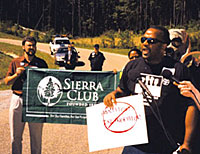

| Club activists and local residents

protest the Army's plan to incinerate chemical weapons at its Anniston

arms depot, below. Above, John McCown, Club environmental justice

organizer, speaks out at a rally just outside the depot gate.

|

As the bus pulled up to the gates of the Anniston Army depot in

northeast Alabama, half a dozen police cars were already waiting for us,

along with a bevy of reporters from regional newspapers and network

television affiliates. Three armed troopers stood in the parking lot,

hands on hips, reflector shades gleaming; three more barred the entrance

to the depot, arms folded across their chests.

Sierra Club activist Rufus Kinney, a member of the Anniston-based

Families Concerned about Nerve Gas Incineration and a professor at

nearby Jacksonville State University, stood at the front of the jam-

packed bus and commandeered the microphone. "Let me get off first and

talk to the officers," he said. "I'll let them know this will be a non-

violent protest; we don't want anyone ending up in jail. I'll find out

where we can assemble, and if there's a line past which we can't go.

Then I'll give the signal for you to come out."

|

| A young Alabama activist and her mother participate

in the anti-incinerator protest at the gates of the Anniston Army depot.

|

The occasion was a June 21 Sierra Club rally in west Anniston, a mostly

poor and African American community that abuts the Army depot, where the

Army wants to fire up a chemical weapons incinerator to destroy the

2,254 tons of outdated but deadly chemical munitions currently stored

there. The Sierra Club, as part of a coalition of environmental justice

and citizens' groups and concerned Anniston residents, is pushing for an

alternative method called neutralization that has been shown to be both

safer and more effective than incineration. The Army is already

committed to using this method at its arms depots in Colorado, Indiana,

Kentucky, and Maryland.

When Kinney gave the sign, we filed out of the bus. Several additional

carloads of locals and Club activists had pulled up, and they now joined

the busload of 50 or so marchers, chanting "Incineration, no!

Neutralization, yes!" One protester was dressed as the grim reaper,

replete with sickle and gas mask, and marchers carried signs and banners

with messages like, "Environmental justice for all" and "Incineration

hurts children and other living things." One little girl carried a sign

that read, "Children should grow, not glow."

As the TV cameras rolled and reporters scribbled, several speakers

addressed the crowd, including Kinney, Alabama Chapter Chair Neil

Milligan, Club Environmental Justice organizer John McCown, longtime

volunteer Ross Vincent, and several local residents.

"This is Crazy In Alabama taken to a new level," charged Kinney. "There

is zero enthusiasm for the incinerator on the west side of Anniston, but

the people aren't being given a choice."

For upward of 40 years west Anniston residents were subjected to PCB

pollution and other toxic releases produced by the Monsanto (now

Solutia) company's local plant. Some residents now have the highest

concentrations of PCBs in their blood of anyone ever tested – anywhere – and

many people feel it is no coincidence that the Army has located one of

its incinerators in west Anniston, where the local populace has little

political power and has already been poisoned.

"We believe that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color bear

disproportionate environmental burdens in our society," said Milligan to

a gathering/workshop the morning of the protest. The workshop was

sponsored by the Club's Environmental Justice Committee and Alabama

Chapter and attracted Club activists from throughout the South, as well

as local citizens.

Arameta Porter was an Anniston schoolteacher until she was beset with

impaired vision and involuntary facial contortions, which rendered her

unable to work. Her doctors believe she was exposed to nerve agents

leaking from the Anniston depot. Another longtime west Anniston

resident, Jeanette Champion, who has difficulty seeing and walking, told

the audience that she had seen whole families wiped out by cancer. At

her side sat her granddaughter, who had to undergo massive surgery when

she was one day old to correct birth defects that Champion attributes to

PCB poisoning.

"My daddy's liver was destroyed by PCBs," she said. "My children have

seen so much death, and I've had so many of my family die in my arms. If

you live past 57 around here it's a landmark."

Craig Williams, director of the Kentucky-based Chemical Weapons Working

Group (CWWG), described how three years ago, in Tooele, Utah – where

chemical incineration is already under way – deadly sarin gas was released

when rocket pieces jammed in the furnace. "Incineration is a perfect

example of the way you don't want to handle this material," said

Williams, "which is to expose it to heat, change it into a gas, and have

a delivery system in the form of a smokestack." He explained that of the

eight sites where toxic nerve agents are set to be destroyed, the four

that have been given alternatives to incineration have all opted for

neutralization. Alabama has never been given that alternative.

Vincent, a chemical engineer who worked with the Club's Colorado Chapter

to successfully stop incineration in favor of neutralization in Pueblo,

told the crowd that incinerators inevitably release toxic chemicals. "No

matter how many layers of containment they put around it, some of that

material escapes," he said.

In preparation for the incinerator to commence operation, nearly 12,600

protective hoods, 8,571 portable air filtration units, and 9,633

"Shelter-in-Place" units – boxes containing duct tape, plastic sheets, a

towel, scissors, and an instructional videotape – have been distributed to

west Anniston residents by the Calhoun County Emergency Management

Association. But a spokesman for the county said only half the homes in

the so-called "pink zone," the 6-mile swath of homes surrounding the

incinerator, have the safety gear.

"This is the only American community where a civilian population has

ever received gas masks," Kinney told an MSNBC interviewer. "That's not

very reassuring, but we demanded them. [The Army] wouldn't have given us

anything except that we demanded protection we have a right to.

"We're not asking that [the chemical weapons] be moved somewhere else,"

he continued. "We believe that everybody should take care of their own

mess in their own backyard. But the Army is far from having the maximum

protection in place that we have a right to by federal law."

In the aftermath of the weekend workshop, the Sierra Club hired the Rev.

Henry Sterling for a three-month stint as an Alabama organizer, based in

Anniston.

On July 16 the Alabama Department of Environmental Management notified

Alabama Governor Bob Riley that it was nearly ready to let the

incinerator begin a "shakedown period" including trial burns of live

agents. In response, Alabama organizer Peggie Griffin and Club activists

coordinated an effort with the CWWG to flood Governor Riley's office

with phone calls "from far and wide," asking him not to sign the

incinerator permit.

On July 31, the state issued its final approval, and Army officials

announced their intention to start burning on August 6. On August 4, the

CWWG filed a Temporary Restraining Order petition to the federal court

in Washington, D.C. (An 11th-hour infusion of cash – more than $10,000 of

it from the Sierra Club – helped the CWWG to prepare this restraining

order.)

According to Brenda Lindell, of Families Concerned about Nerve Gas

Incineration, the governor requested the Army not start burning the

chemical weapons before granting him the authority to shut down the

incinerator if there were any problems, but this was denied, and the

Army plans to go ahead regardless.

Ever since the June 21 rally at the Army depot, the fight against the

Anniston incinerator has risen startlingly fast from a local issue to a

story of national import. National media, including NBC Nightly News,

CNN, and various cable news networks, have featured segments on

Anniston, and a groundswell of public opposition to the incinerator has

begun to grow. Another, larger anti-incinerator rally is planned in

Anniston on August 16, regardless of whether or not the incinerator has

been fired up.

The people Ross Vincent calls "ragtag activists from small communities

around the country" have made their case that there's a better way to

dispose of chemical weapons than burning them. So far, the Army is not

listening. Residents of Anniston are hoping the federal court will.

Up to Top

|