By Bob Sipchen

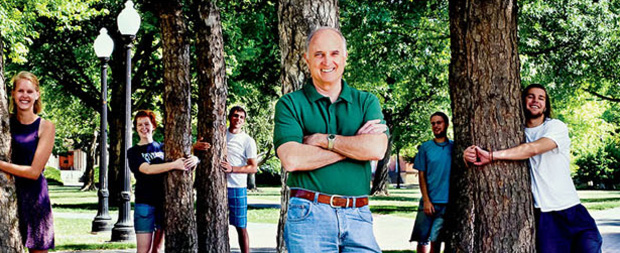

Professor David Orr and his students, Oberlin College, June 2012. "Hope," he often tells them, "is a verb with its sleeves rolled up." | Photo by Raymundo Garza

Orr's view of hope during an age when the parts per billion of carbon in the atmosphere is approaching catastrophic levels is not unlike his view of patience: Both are practical values. "It's a tough time to be a teacher," the professor says. "Kids' hormones tell them to be optimistic. The numbers tell them differently." So he has taken a lesson from E.F. Schumacher, author of Small Is Beautiful and A Guide for the Perplexed. "Schumacher said that if you ask, 'Can humankind survive?' and answer no, people become despondent. If you answer yes, they become complacent. So instead, [Schumacher] says, 'Get down to work.'"

With the school's bell tower chiming in the distance, we step beneath a big carport covered with solar panels. A much bigger, 3-megawatt solar array will come online by the end of summer. It will help the college meet its goal of weaning itself from coal-fired energy in three to five years. Using geothermal, gas cogeneration, and efficiency measures, the school and the town are aiming to become carbon neutral by 2025.

Ecotopia, as it happens, struck me as didactic and sappy—awful, actually. Yet there's no denying that 40 years after the book's publication, the future it predicted is beginning to blossom, at least fitfully, in little Oberlin.

As he wheels his red Prius onto a side street, Orr says that he met Callenbach a few times and that he "hadn't thought of the connection." Maybe that's because the Oberlin Project, unlike Callenbach's naive fantasy, is "hugely pragmatic," he says. A moment later, he points out an abandoned supermarket and says that the project team is twisting the arm of a local organic-grocery owner, trying to persuade him to take it over. Then he shows me an elementary school that will be rebuilt along the lines of the environmental studies building and talks about plans to expand the definition of education in Oberlin to include classes in which local builders, welders, farmers, and craftspeople will share their skills.

When I raise the antique-shop owner's concern that the plan will cost locals money, Orr responds with a fusillade of data about funding mechanisms, including investments, tax credits, and bonds. He says that switching to clean energy and job-generating policies will actually save the townsfolk money almost immediately—as if that matters, he might have added, given the massive economic hardship that climate disruption is about to foist on people everywhere.

Before dumping me back at the inn, Orr points out a cylindrical edifice that once housed the town's coal gas but is now on the brink of becoming a museum to celebrate Oberlin's role as an Underground Railroad crossroads. He recommends a book about a pivotal moment in local history. It tells the story of the Oberlin abolitionists who got wind that bounty hunters had captured several runaway slaves, surrounded the jailhouse, and refused to leave until the captives were released. The book, he says, is called The Town That Started the Civil War.

Orr has met enough journalists to know that we are skeptical, averse to being spun. So he stops short of connecting the dots between this historic event and his emerald dream. Still, I'm pretty sure he knows he has planted a narrative seed, figuring I won't be able to resist ending this story with a pointed reflection about how the course of human events just might possibly be changed by a few brave souls embracing a bold vision.

Cunning man, Orr.

Bob Sipchen is Sierra

's editor in chief.

Rural mothers become solar engineers.

Ditching the cubicle for a summer outdoors.

Students fight to kick coal off campus.