By Bob Sipchen

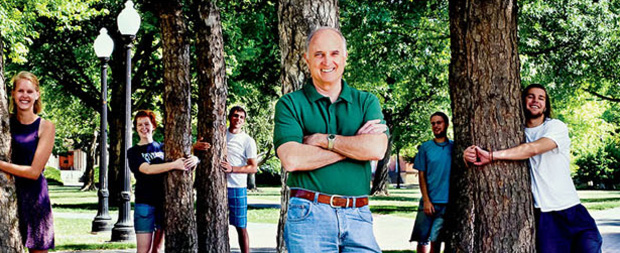

Professor David Orr and his students, Oberlin College, June 2012. "Hope," he often tells them, "is a verb with its sleeves rolled up." | Photo by Raymundo Garza

On the day of my visit to Oberlin, Orr, who calls himself a type A personality—"possibly triple A"—is still moving fast. The married father of two grown sons has just returned from giving the commencement address at Colorado's Naropa University and is flying to Washington, D.C., in the afternoon for more speeches and fundraising. But first he's eager to show me where the $55 million that has already been raised has gone and where the additional $75 million the school is trying to collect will go.

Orr leads me out of the college-owned hotel, noting over his shoulder that it will, if all goes right, soon become the LEED "beyond Platinum" centerpiece of the project's 13-acre green arts district. An energy-efficient conference center, Orr says with a confident wave of his hand, will routinely draw the sorts of folks who have the influence to help the project's big ideas evolve and spread. A 20,000-acre greenbelt surrounding the town will provide organic food for a new four-star hotel and restaurants.

After crossing the street, Orr sticks his head inside the Apollo Theater, which first opened in 1913 and now bustles with a construction crew putting final touches on an environmentally sound upgrade. Oberlin faculty will use the theater to teach cinematography to students and interested area residents. Other elements already completed or in the works include a black box theater; solar-powered, LEED-rated construction projects with community colleges and local schools; and affordable housing. City administrators, educators, business leaders, and philanthropists have been tapped for their expertise, and as one of 18 projects in the Clinton Climate Initiative, the college and town's combined efforts are becoming a template for how other entities and places (military bases, for example) can stop contributing to climate disruption and become carbon neutral.

"This little town, with its good people, could be—with just a bit of social and political acupuncture—the first example of integrated sustainability," Orr says.

Orr, 68, grew up in Pennsylvania farm country, the son of a father who was a minister and a professor. It was a time when Thoreau's all-American respect for humans' protective place in nature had been amplified into an alarm by such authors as Aldo Leopold and Rachel Carson, and when social concerns were being refracted in a thousand directions by the thinkers of the 1960s. "The environmental movement," Orr says, "helped me connect the dots between urban unrest, civil rights, Vietnam, and a society that had come off the rails."

He began his academic career teaching political science at Agnes Scott College in Georgia and then at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Fired up by the ideas of Theodore Roszak (The Making of a Counter Culture) and Ian McHarg (Design With Nature), among others, he soon came to believe that academia was so "marinated in complacency" that it was squandering the enthusiasm of students eager to apply their newfound knowledge to the mess they'd inherited. "The academy wanted to separate the feeling part of people from the analytical part," he says. Orr encouraged students to explore the connections between land, food, health, and shelter: "I wanted to prepare young people for life on Earth."

With his brother, Wilson, Orr bought a 1,500-acre farm in Arkansas's Ozarks and created the Meadowcreek Project, an experimental school that hosted what Orr calls the "first conference on sustainability."

By the end of the 1980s, Orr was ready to move on. "I was a better pioneer than settler," he says. He landed at Oberlin in 1990 as a professor of politics and environmental studies.

"I can't imagine any other institution that would let me do what I've done," Orr says as he leads me across a park where the identities of the town and the eponymous 180-year-old campus meld. In the administration building, Orr introduces a staffer as "pure trouble" and me as "an emissary from Dick Cheney's office." When the president's chief of staff volunteers that her biggest job is "keeping David under control," a wisp of a smile crosses Orr's face. Continue reading >>

This article has been corrected.

Rural mothers become solar engineers.

Ditching the cubicle for a summer outdoors.

Students fight to kick coal off campus.