|

From Montana to Virginia, Sierra Club, American Indians join hands to win land protection

By Kim Todd

Against the yellow rock walls, they purified themselves with sage smoke, told stories of this legendary valley of peace where even warriors put down their weapons, and admired 1,000-year-old paintings of shields and a bear with long claws. After a day in the Valley of the Chiefs in southeastern Montana, American Indian and environmental leaders emerged with a powerful coalition, ready to take on the Bureau of Land Management and Anschutz Exploration Corporation. Against the yellow rock walls, they purified themselves with sage smoke, told stories of this legendary valley of peace where even warriors put down their weapons, and admired 1,000-year-old paintings of shields and a bear with long claws. After a day in the Valley of the Chiefs in southeastern Montana, American Indian and environmental leaders emerged with a powerful coalition, ready to take on the Bureau of Land Management and Anschutz Exploration Corporation.

Leaders from three tribes - Blackfeet, Comanche and Crow - and Sierra Club staff and volunteers hiked the three miles into the valley together last May, part of a joint effort to preserve the canyons from an exploratory oil well.

The BLM designated the site, also called Weatherman Draw, an "area of environmental concern" two years ago, but the Anschutz lease predated that designation. In February, the agency decided the drilling could go forward, bringing with it a road and the potential for further damage: Graffiti of graduating classes, bullet holes and a sketch of Bart Simpson already mar the rock art panels. The coalition prepared to appeal the agency's decision.

"There are gains for both of us-the Sierra Club is going to save a place that environmentally needs to be saved. The Indian people will be protecting their religious cultural sites," said Howard Boggess, an oral historian with the Crow tribe. "There's power in numbers."

More and more Club chapters and groups are discovering this power as they form partnerships with tribes on issues from sprawl to clean water and environmental justice.

In Virginia, Club activists worked with the Mattaponi tribe to halt a reservoir that would have damaged forest lands and fish. In Wyoming, tribes partnered with the Club to protect Medicine Wheel, a stone circle with 28 spokes, often referred to as the "American Stonehenge." In New Mexico, Miss Navajo Nation appeared at a rally to voice her opposition to drilling in the Arctic.

In South Dakota, Charmaine White Face bridges both worlds as a Club organizer and an Oglala Lakota (Sioux). Taking outreach to new places, she gathers postcard signatures at powwows and distributes flyers at tribal meetings. In October, she organized a conference to educate tribal members about federal environmental laws and regulations, including the National Environmental Protection Act.

During the wild forest public hearings in 2000, her outreach efforts brought people from the Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River and Standing Rock reservations to speak for the Black Hills. Their comments made the Rapid City hearing one of the few in the area where those in favor of the wild forest initiative outnumbered those opposed.

But cross-cultural challenges still come up: As White Face rewrote a Club grasslands brochure in Lakota, she found the idea of "wilderness" as a vast tract of unpeopled land didn't translate.

"To us, there's no such thing as wilderness because all of these places were occupied," said White Face. "Wherever we didn't live, other people lived."

Sometimes, misapprehensions arise on both sides. For Club members used to doing business at modem-speed, a slower pace can take some getting used to. Not everyone has e-mail. Not everyone can jump on a plane at a moment's notice and fly to a congressional hearing. On the other hand, American Indians can be put off by a culture that tolerates interruptions and doesn't take the time to understand their traditions.

"In a lot of these communities people have no idea what the Sierra Club is," said Andy Bessler, the Club's environmental justice organizer in Arizona. "Other people feel that it's a huge monster coming into their community."

It's not so much fear as caution, he said, a wariness that time and consistency can overcome.

After the success of the San Francisco Peaks campaign, where Bessler and the Club worked with the Hopi and the Navajo to shut down a pumice mine that was serving up stone to pre-wash and weather blue jeans, tribes began seeking partnership on other issues. Hopi activists came to the Club for help stopping Peabody Coal from damaging a local aquifer, and a Zuni councilman wanted to collaborate to protect the Zuni Salt Lake from a water-thirsty coal mine proposed nearby. Now the campaigns are broadcasting radio announcements in English, Navajo and Hopi and printing buttons that say "Water is Life" in those three languages and Spanish.

"The length of the San Francisco Peaks campaign let people know where my heart is," said Bessler. "I had gained some understanding and respect for the complexity of their culture."

And when environmental activists and tribes do come together, even a small, halting campaign can quickly gain momentum.

Right after the trip through Weatherman Draw in May, the coalition made the tough decision to publicize the rock art and sacred nature of the Valley of the Chiefs. This move risked attracting vandals but it upped public awareness of the site's cultural value and drew articles in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. The hundreds of e-mails and phone calls and letters sent by Club organizer Mary Wiper and Boggess increased the size of the coalition. The tribes' willingness to throw their weight as sovereign nations behind the protest and the Sierra Club's contribution of resources and knowledge of federal laws and agency processes drew national attention to the remote valley.

In June, Rep. Nick Rahall (D-W.V.) introduced H.R. 2085, the Valley of the Chiefs Native American Sacred Site Preservation Act of 2001, which would protect the site from further mineral exploration, and the group planned a press conference and visits to legislators' offices to gather support.

Soon the group of tribal leaders and environmentalists found themselves walking shoulder to shoulder through another kind of canyon - the corridors of the Capitol, where the walls displayed pictures of George Washington and pilgrims at Plymouth Rock, rather than tribal shields.

The tribe members and the environmentalists each felt they were taken more seriously flanked by the other, according to Wiper, and they made an imposing group facing reporters.

"Between Kathryn [Hohmann], Mary and the four tribal leaders - we could answer any question. It was very impressive," said Boggess.

Currently, the oil prospecting is on hold for six months as Anschutz and the tribes discuss trading drilling on reservation land for drilling in Weatherman Draw. As these negotiations go forward, the Club is playing a smaller role, but Wiper still feels pride about how much was accomplished and her part in bringing such a diverse group of people together.

"One of the Blackfeet leaders said to me, 'You're the glue,' " she recalled.

And so far, the bond is solid.

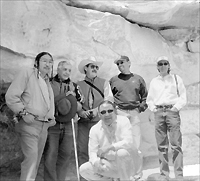

Photo: Sacred Ground: Tribal leaders, Club organizers and volunteers toured Weatherman Draw - a site sacred to the tribes and filled with rock art - last May. The group emerged energized to fight together against oil drilling scheduled for the Montana valley. Left to right are Clifford Tailfeathers, Blackfeet; Howard Boggess, Crow; Bill Redfield, Crow; David Gordon, Blackfeet; Jimmy Arterberry, Comanche; and Jimmy St. Goddard, Blackfeet, in front.

Up to Top

|