sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - sept/oct 2012 - grapple: climate change in the classroom

Climate Change in the Classroom | Critter: Original Blue Bloods | The World's Coal Stack | Next Big Thing: Eating Bugs? |

On the One Hand: Fleece | Worst Congress Ever | Up to Speed

Michael Waraksa

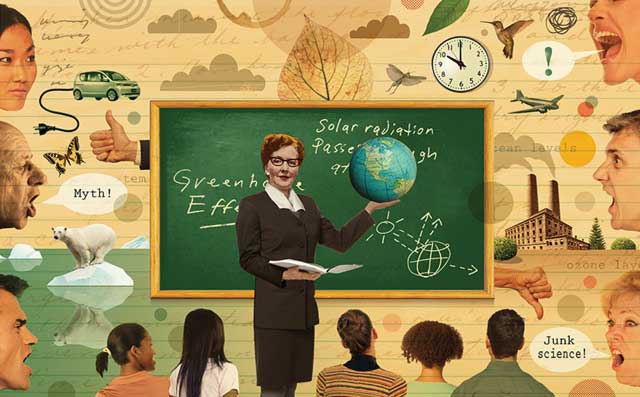

AN INCONVENIENT SUBJECT

Climate change in the classroom: too controversial—or too depressing?

When science teachers under attack sought help from the National Center for Science Education in years past, the issue was usually evolution. But the new classroom bogeyman is not the bearded visage of Charles Darwin; it's an inconvenient former vice president named Al Gore.

"Climate is the new hot-button issue in education," says Mark McCaffrey, who launched the Oakland, California-based center's new climate-policy program. "Unfortunately, where it's taught at all, it's taught incompletely, or incorrectly as a scientific controversy. Mostly it's missing entirely from the curriculum."

Eight out of 10 teachers polled by the University of

Colorado's Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) this year say they have faced climate-change skepticism from school administrators and parents; 47 percent voluntarily teach "both sides." In California, irate parents accused a San Mateo County high school teacher of "brainwashing" students by showing Gore's An Inconvenient Truth; now the local school superintendent requires a signed parental permission slip for classroom viewing of the film. This spring, Tennessee adopted a law that gives teachers license to present the "scientific strengths and weaknesses" of both evolution and global warming. A similar measure died in committee in Oklahoma. Such efforts demand that educators "teach the controversy"--a controversy that major scientific organizations across the world say doesn't exist.

School districts not cowed by climate-change deniers will soon have good resources available. A curriculum for middle schools by the Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network has peer-reviewed lesson plans that focus on scientific evidence and avoid policy prescriptions. And the nonprofit Next Generation Science Standards is including a rigorous climate-change component in its proposed voluntary national standards, which thus far have the support of 26 states.

Susan Buhr, outreach coordinator for CIRES, notes that an obstacle to any climate curriculum is that melting sea ice and rising sea levels are depressing fare for kids in seventh and eighth grade. That's why she advocates climate lessons that accentuate how humans can respond to the challenge. "That's essential," Buhr says. "People don't learn well when they're scared. And no one wants to send children home in tears." --Edward Humes

Critter: Original Blue Bloods