sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - january/february 2010 - the west without coal

The West Without Coal

The lights of Los Angeles would burn just as bright—except they might have to be LEDs

By Paul Tullis

Map: What Powers the West

As we approach the Grand Canyon from the south at 22,000 feet, the three 775-foot towers of the Navajo Generating Station loom from the horizon. The stacks, which have been spewing smoke almost constantly since the plant opened in 1974, are among Arizona's tallest structures. The copilot says that the first thing passengers usually notice is Lake Powell, the shrinking 254-square-mile reservoir from which Navajo draws 8 billion gallons of water a year for cooling. But when the light is right and the sky is clear, this mammoth coal-fired power plant on the Navajo Nation rivals one of the most significant geologic features on the face of the earth.

Navajo's smokestacks spew mercury, sulfur dioxide, nitrous oxide, and other substances that poison rivers and crops and developing fetuses throughout the Four Corners region. Threatening the entire globe, however, are the 20 million tons of carbon dioxide they pump into the atmosphere each year--equivalent to the emissions from 3 million cars. That makes Navajo the nation's fifth-largest power plant source of the greenhouse gas. The CO2 is the inevitable byproduct of burning coal to generate enough electricity for 2 million homes. Twenty-one percent of that electricity is transmitted via 500-kilovolt wires to Los Angeles, 430 miles to the west.

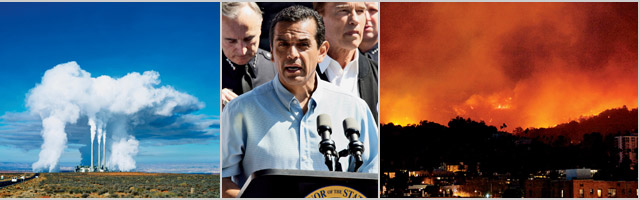

L.A. mayor Antonio Villaraigosa vows to change all that. As a member of California's state assembly in the 1990s, Villaraigosa had a commendable environmental record, but global warming didn't really hit home for him until May 2007, the year L.A.'s Griffith Park--one of the largest urban parks in the country--burned for three days at the end of Southern California's rainy season. "Los Angeles was undeniably feeling the impact of climate change," the mayor said. "That was my 'Aha!' moment." (Climate-change models predict increased wildfires in semiarid areas.) So last year, in his second inaugural address, Villaraigosa announced that by 2020 Angelenos would "permanently break our addiction to coal."

The Navajo Generating Station (left) and other coal-fired plants provide 42 percent of L.A.'s electricity. After a wildfire ravaged the city's famed Griffith Park in 2007 (right), Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (center) got serious about climate change, vowing to "break our addiction to coal" by 2020.

At the time, Los Angeles got 8 percent of its electricity from renewable sources and 42 percent from coal--not only from Navajo but from the Intermountain Generating Station in Utah as well. If all goes according to plan, sometime in 2010 the city's proportion of renewable power will grow to 20 percent. Villaraigosa has committed to boosting that number to 40 percent by 2020 and to 60 percent by 2030. This mandate has set the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) racing to find more energy from renewables for its nearly 4 million customers.

Villaraigosa's quest raises a striking possibility: Through a combination of geographical accident, citizen activism, and political leadership, the Pacific coast states could wean themselves from coal. The coastal cities in particular are intent on establishing a modern vision of "ecotopia." Already, Seattle gets less than 1 percent of its power from coal and recently sold its ownership interest in a coal plant; its new mayor, Mike McGinn, is the former chair of the Sierra Club's Cascade Chapter and an activist in the Club's Cool Cities program who made it a point to bicycle to campaign events. Portland, Oregon, has a draft "climate action plan" that calls for reducing carbon emissions by 80 percent from 1990 levels by 2050.

Los Angeles' 120-megawatt Pine Tree Wind Project, in the rugged hills above the city of Mojave, California, is the largest municipally owned wind farm in the country. The turbines' enormous blades sweep areas the size of football fields, providing power to some 56,000 homes.

Los Angeles' 120-megawatt Pine Tree Wind Project, in the rugged hills above the city of Mojave, California, is the largest municipally owned wind farm in the country. The turbines' enormous blades sweep areas the size of football fields, providing power to some 56,000 homes.

To that end, Mayor Sam Adams has called on Portland General Electric (PGE), one of two utilities serving the city, to phase out coal. The other major Oregon utility, Pacific Power, has had a moratorium on power from new coal-fired plants for the last two years. Pacific Gas and Electric Company, which serves 15 million people in the San Francisco Bay Area and throughout northern and central California, is snatching up power-purchase agreements from solar farms before they're even built. San Diego Gas and Electric Company, which serves 3.4 million people, gets half as much coal power today as it did five years ago and says it doesn't plan to renew its last coal contract, which expires in 2013.

Then there's Los Angeles. "We've got an influential and high-profile city and leadership, the nation's largest municipal utility, and some of the most ambitious goals anywhere for transforming our energy supply," said Martin Schlageter, campaign director for the Coalition for Clean Air, a statewide advocacy group. But should L.A. stumble, he warned, everyone will say, "'That's what happens when you set ambitious goals,' instead of, 'If you can put the second-largest city in the country on the path toward a more sustainable future, then I guess we can do it too.'"

Some may view L.A.'s efforts as ironic, and therefore its commitment as suspect. Los Angeles, after all, is the birthplace of sprawl and smog, the thief that stole water from the Owens River for its burgeoning suburbs, the butt of many a New Yorker's jokes. Yet despite its reputation for shallowness, Los Angeles is leading the fight against global warming. One of its congressional representatives, Henry Waxman, shepherded climate-change legislation through the U.S. House. It has the highest recycling rate (65 percent) of the nation's largest cities and is home to a remarkably successful coalition of wilderness preservationists and green-energy champions.

Under green-energy pioneer David Freeman, L.A.'s Department of Water and Power is going solar.

Under green-energy pioneer David Freeman, L.A.'s Department of Water and Power is going solar.Among these is David Freeman, recently named—for the second time in his long career—head of L.A.'s fabled Department of Water and Power. Now 83, Freeman has been at the center of U.S. energy policy since before the United States had an energy policy. He drafted the first speech on energy delivered by a president to Congress (for Richard Nixon, in 1971) and was instrumental in establishing the EPA and passing the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. When he headed the DWP from 1997 to 2001, the agency sold its interest in the coal-burning Mojave Generating Station, near Laughlin, Nevada. Freeman ruefully told me how his successor bought it back—only to see the $90 million investment evaporate after a judge ordered the plant closed for violating the Clean Air Act 40,000 times in less than a decade.

When I met Freeman at his City Hall office, it was 91 degrees outside, and L.A. was pulling down 5,382 megawatts of power. (The department's all-time high is 6,102 megawatts, an amount greater than the total electrical generating capacity of Nigeria.) In an effort to lower that number, Freeman has overseen the distribution of 1.4 million compact fluorescent bulbs to DWP customers and converted 140,000 streetlights, as well as every traffic light in the city, to low-power light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

But efficiency measures will only take you so far, and L.A. is urgently seeking renewable-energy sources. Freeman noted that his boss, Mayor Villaraigosa, is "determined that we get things sufficiently in place or under construction so that by the end of his term [in 2013] no one can reverse it." Freeman's portfolio includes the new Pine Tree wind farm in the Mojave Desert (its 120 megawatts from 80 General Electric turbines make it the largest city-owned wind farm in the country); a facility in Playa del Rey that extracts methane from sewage and turns it into energy; and a 400-megawatt geothermal project near the Salton Sea, a barren lake 130 miles southeast of the city. "We're cooking a lot of meals in the kitchen that we're just not ready to talk about yet," Freeman said, promising a major announcement by the end of 2009. "We have a lot of big ideas."

One thing he is ready to talk about is a plan to take advantage of Los Angeles' 276 annual days of sunshine. In the late '90s, Freeman put into place a rebate program that absorbs about half the installation price for home solar arrays. But even with government tax credits piled onto the rebate, solar has never contributed more than 2 percent to L.A.'s energy mix. Freeman plans to dramatically increase that figure, in part by selling the concept to ordinary citizens at workshops like the one I attended near my house in Los Feliz.

A crowd of 100 listened as moderator Randy Howard described plans to build new solar arrays in the desert, buy power from solar farms, and help pay for homes and businesses to put panels on their roofs. Even renters and the less well-capitalized will be able to purchase "virtual" solar panels through a program dubbed SunShares, so they can get in on the fun. The solar initiatives are going to be expensive, but, as Howard pointed out, when you're building renewables facilities, you're essentially buying 30 or 40 years' worth of fuel, so the cost is all on the front end.

"We've taken polls," Freeman told me a few days later. "People are willing to see their health bill reduced while their energy bill goes up a little. They understand the connection."

Whatever solar and other renewables projects Freeman is or isn't able to bring on line, his Department of Water and Power owns no coal plants. Should L.A. cancel its coal-power contracts, the plants' energy may well be sold elsewhere. But in the Pacific Northwest, another strategy is taking shape: to shut down the coal plants altogether.

Portland mayor Sam Adams (above) has called on the local utility to phase out coal, while city sustainability manager Michael Armstrong (below) rides the ride, scoping out new ways to reduce power consumption.

Portland mayor Sam Adams (above) has called on the local utility to phase out coal, while city sustainability manager Michael Armstrong (below) rides the ride, scoping out new ways to reduce power consumption.In Portland, this strategy is unfolding on two fronts: promoting alternatives and ratcheting up the cost of business as usual. Straddling both is Bruce Nilles, director of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal Campaign, which since 2005 has succeeded in closing or canceling plans for 107 existing or proposed coal-fired plants.

"The Northwest and California are two places where coal has never had to defend itself," chiefly because coal is not mined there, Nilles said. "People have never had to ask, 'Do we want coal here?'" Nilles and I spoke at the Club's Portland office, halfway between a medical marijuana dispensary and a worker-owned bicycle shop. Afterward, in a highly unscientific survey at the Citybikes co-op, Portland's most committed fossil-fuel shunners were asked where the city gets its electricity. Coal was cited only once. In fact, the 585-megawatt Boardman coal plant, 160 miles to the east in the Columbia River Gorge, is the source of 15 percent of Portland's power; other coal plants provide an additional 25 percent.

In a city as proud of its light rail and smart-growth policy as Portland, that should be a point of shame. And to people like Michael Armstrong, the city's senior sustainability manager, it is. As his title suggests, Armstrong focuses on promoting alternative energy and conservation. We met in his boss's conference room overlooking the stormwater-filtering green roof of the newly constructed Cyan/PDX apartments and the green office building at 200 Market Street, which just switched out its conventional lightbulbs for LEDs. Just out of sight is an office building partly powered by windmills. Armstrong is under orders to dramatically reduce Portland's energy consumption, and it's happening all around us.

"What we want to put ourselves on the hook for," he said, "is to reduce energy use such that we don't need that coal. If we can reduce by 40 percent, we can have a viable conversation about shutting that coal plant down."

Finding that efficiency is Armstrong's job. He described a program his Bureau of Planning and Sustainability runs in conjunction with Green for All (a national group working to build a green economy) that retrofits older homes in the city for energy efficiency. Paid for in part by federal stimulus dollars, the 500-home pilot program upgrades insulation, windows, and other features. The cost is tacked on to the utility bill but spread out over 15 years; the energy savings typically mean the net cost doesn't go up even with the extra charge. The program, coming at a time when the housing and credit markets are reeling, has proved popular beyond the usual crunchy crowd.

"It used to be that the energy nerds came to the table to talk about what kind of incentives we could offer to get people to switch out their lightbulbs," Armstrong said. "Now the unions are at the table saying, 'Put my people to work—we want to save energy too.' Everybody sees this as the model, and we've got 100,000 homes that need insulation. That's the kind of scale where we can have a serious conversation about attaining 40 percent [energy savings]"—and getting off coal.

The second front against the plant is a legal one—to make utilities pay the full cost of coal power. As is, Boardman makes electricity at about two cents per kilowatt-hour, an incredibly cheap rate. The strategy is being executed by Aubrey Baldwin, a lawyer with the Pacific Environmental Advocacy Center at Lewis and Clark College's law school, which filed a complaint in federal court against Portland General Electric for allegedly violating the Clean Air Act at Boardman for many years.

"Boardman has had thousands of violations over five years, at $37,500 per violation," explained Baldwin over breakfast on a cool Portland morning last fall. PGE denies any violations. In addition, a Sierra Club analysis claims it would be cheaper for the utility to shut the plant than to spend the up to $600 million it would take for it to meet new federal emissions rules. Yet another potential cost, said Doug Howell of the Club's Beyond Coal Campaign, would be Boardman's "carbon liability" from the climate bill Congress ultimately passes. The House version, approved in June, prices carbon dioxide emissions at $20 per ton, which could put Boardman on the hook for $80 million annually. Put together, Howell said, these charges "dwarf the modest cost increase from getting rid of it." PGE could, of course, pass the costs on to ratepayers, but Oregon customers are accustomed to cheap electricity (about half what Angelenos pay), and PGE is legally required to provide power at the lowest possible rate.

PGE spokesperson Patrick Stupek hastened to point out that the utility has invested $1 billion in the 275-megawatt Biglow Canyon Wind Farm and is progressing toward a goal of having 25 percent renewables by 2025. But after modeling various planning options—including shutting the coal plant—he said, the utility concluded that "the portfolio that offers our customers the best mixture of cost and risk includes continued operation of Boardman with aggressive new emissions controls."

Getting off coal, said Stephanie Pincetl, director of the UCLA Urban Center for People and the Environment, "is going to be really hard." Utilities like PGE and DWP are under a lot of constraints. Indeed, almost palpable in my discussions with utility representatives was frustration with the pressure they get from environmentalists who don't appreciate their obligations—paramount among which is providing nonstop power.

For example, said Art Sasse, spokesperson for Oregon's Pacific Power, "the wind doesn't blow all the time, and when it does, it tends to be during off-peak times. So if you're replacing coal with wind, you need to add natural gas." Gas from the best new plants has a carbon footprint about half that of coal, but the plants cost $200 million. In Los Angeles, a DWP commissioner, speaking anonymously, grimaced as he explained that his agency is "almost compelled to have natural gas" for reliability reasons. "The most important job we have, besides doing it safely, is to keep the lights on," he said.

In addition to the practical concerns, Pincetl said, "there's a whole set of political constraints." Environmentalists are keen to establish a new energy order, but they don't have a whole lot of allies. At the DWP solar workshop, for instance, the only other identifiable constituency was workers from the union halls who wanted to make sure they got in on the action of building all that solar infrastructure. But labor is far from unified on the issue. In March 2009 a bond measure for solar projects was defeated after other unions opposed the monopoly on jobs it would have given to the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

Getting the West off coal this decade is an enormous undertaking. It will require politicians following up on their lofty pronouncements; relentless, informed organizing by grassroots activists; constant legal pressure; and (two words not often seen together) bureaucratic creativity. But first, it may take L.A. to lead the way—which new DWP boss David Freeman is determined to do.

"I'm not in the habit of recommending things to my boss unless they can be done," he said. "We're going to be the agency that people point to and say, 'Yes—it can be done.'"

Paul Tullis has written on environmental affairs for Salon and Men's Journal.

He blogs at trueslant.com/paultullis.

What You Can Do About Coal

Washington, Oregon, and California are taking the lead on clean energy, but the West's dirty secret is that a significant amount of its power still comes from coal. In addition, mining in the West supplies 60 percent of the nation's coal. Mining and burning coal hurt the health of local families and communities, whether in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and Montana or the desert Southwest.

To win back the West from dirty energy, the Sierra Club's Western Coal Campaign has three goals: (1) to stop construction of new coal plants; (2) to keep Alaska's enormous coal reserves from being developed and to limit the expansion of the Powder River Basin mines; and (3) to create coal-free zones first in individual states and eventually in larger areas. Coal freedom would involve retiring all existing coal plants, ending imports of coal-generated electricity, and meeting each state's needs with clean energy.

Find out what's happening in your state at sierraclub.org/coal.

—Dan Ritzman, Western Coal Campaign director

Photos, from top: Peter Bennett/Ambient Images; Jim Zuckerman/Alamy; UPPA/Photoshot; Chuck Green/ZUMA Press; Los Angeles Department of Water and Power; Ewan Burns; Enko Photography; Ty Milford

This article has been corrected subsequent to publication.