sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - january/february 2010 - elephant man

Elephant Man

Twenty years ago, Richard Leakey saved Kenya's elephants from poachers by outfitting rangers with helicopters, automatic weapons, night-vision goggles, and shoot-to-kill orders. He has since been arrested, censored, and beaten, and lost his legs in a suspicious plane crash. Now Africa's most famous conservationist is enlisting a new army to save the continent's ever-threatened wildlife: frontline bloggers.

By Susan Zakin

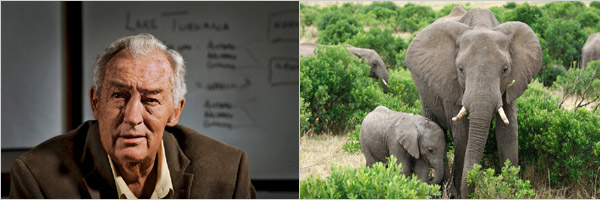

Richard Leakey in his office at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, September 2009 (left).

African elephants, Samburu National Reserve, Kenya (right).

The Peponi Hotel is unusually quiet. The chief tour guide lounges on a bench outside. Jonas, the hotel's well-read barman, polishes wine glasses for what must be the third time. It's summer, low season on the island of Lamu, and Kenya's election troubles have frightened away the usual crowd of celebrities, minor aristocrats, and delicately faded ex-models. Jonas catches my eye.

"Leakey isn't here?" he asks.

I shake my head, glance at my watch. Richard Leakey, Kenya's most famous conservationist, has promised to pick me up and take me to his house for lunch, and he appears to be late. Almost idly, I turn to the Indian Ocean, where a speedboat bobs offshore. From behind the wheel, a bulky man gestures for me to join him. It's Leakey, and he's not coming ashore.

I wade out to the boat, where Leakey tells me he hasn't been to the Peponi in years, muttering something about the "beautiful people." I'm not surprised: His family has long had an uneasy relationship with the country's wealthy colonialists. Richard's father, the late anthropologist Louis Leakey, wrote that as a boy he dreamed in Kikuyu, the language of Kenya's dominant ethnic group. And Richard's childhood friendships with black people so provoked his white schoolmates that they forced him into a cage and poked him with sticks, calling him "nigger lover."

Today, at age 65, Richard Leakey comes to Lamu not to socialize but to sail, to relax, and, most of all, to be alone.

As we motor across the bay toward Leakey's vacation home, he grips the wheel hard to keep from falling, and I remember the story of his legs. In 1993, the Cessna he was flying crashed in the Great Rift Valley, an incident widely thought to be an assassination attempt by someone unhappy with Leakey's antipoaching zealotry. Both of his legs were amputated at the shins, and he now walks on prostheses.

Leakey drives the boat fast, and soon we arrive at his house, which is as serene as one can find on Lamu: far from the bustle of the island's casbahlike Old Town, rambling yet spare. He motions me upstairs to the rooftop terrace, where we sit in lounge chairs surrounded by the branches of fruit trees he planted almost 30 years ago.

Holy smoke: In July 1989, Richard Leakey arranged the public immolation of 12 tons of confiscated ivory, worth more than $3 million (left). Richard Leakey posing with his good friend Homo erectus in England in 1980 (right).

Holy smoke: In July 1989, Richard Leakey arranged the public immolation of 12 tons of confiscated ivory, worth more than $3 million (left). Richard Leakey posing with his good friend Homo erectus in England in 1980 (right).

For decades, this retreat has provided a much-needed refuge from what has been, by anyone's estimation, a busy life. His father remains a dominating figure in Kenya more than 35 years after his death. The elder Leakey was a true polymath: a linguist and anthropologist whose interests ranged from evolutionary biology to the study of handwriting. Louis and his wife, Mary, are best known for discovering human ancestors in Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge.

By the 1960s, declining health made it hard for him to do fieldwork, so he hired three young women to help him study primates: Jane Goodall, Birute Galdikas, and Dian Fossey. In the rest of the world, some of those names are now more recognizable than Leakey's, but in Kenya, wags still refer to the trio as "Leakey's Angels."

Richard, the second of three sons, was 6 when he found his first significant fossil and 22 when he found a large unexplored fossil bed that would yield many legendary discoveries. Thanks to his astute political maneuvering, he was made director of the National Museums of Kenya at 25. Richard's talents lay not in academia but in administration and a certain kind of hustle and inventiveness. Those skills would eventually land Leakey in a position of unprecedented power.

In the 1980s, ivory poachers were decimating Kenya's elephant and rhino populations, exacerbating a decades-long decline in the region's wildlife. In 1989 the country's notoriously corrupt president, Daniel arap Moi, asked Leakey to lead the agency that would become the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). Leakey modernized the agency, making conservation its primary mission and officially ending the era of the Great White Hunter in Kenya. He raised salaries, bought uniforms and vehicles that actually ran, and personally shook hands with so many employees that he could have been a presidential candidate —and more than a few people believed he saw himself as just that.

Leakey advises Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi in 2000, a year before Leakey was stripped of his power to investigate government corruption.

Leakey advises Kenyan president Daniel arap Moi in 2000, a year before Leakey was stripped of his power to investigate government corruption.Poaching was so severe that President Moi had given park rangers permission to shoot to kill. Leakey provided them with the means to do it: helicopters, automatic weapons, and night-vision goggles. An average of one poacher was killed every four days during Leakey's first year at KWS, according to Raymond Bonner's book At the Hand of Man: Peril and Hope for Africa's Wildlife (Vintage, 1993). It is a record he still feels the need to defend by saying that the vast majority of poachers were not hungry locals but heavily armed professionals from Somalia.

Leakey reinvigorated the agency but proved even more adept at public relations. Appalled to discover that his own agency had given a sweetheart deal on confiscated ivory to a well-connected East Asian businessman, Leakey canceled the transaction and sold Moi on the idea of setting fire to 12 tons of ivory worth more than $3 million. After a photograph of the giant bonfire appeared in newspapers around the world, the World Bank anted up an unprecedented $210 million to fund conservation in Kenya. In addition, the European Economic Community banned ivory imports, and the international wildlife conservation authority, Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species and Wildlife (CITES), gave African elephants the highest possible level of protection.

As head of KWS, Leakey was widely seen as a bold leader—perhaps too bold. After he refused to accede to President Moi's demands that he reinstate 1,640 agency employees dismissed because of corruption allegations or inefficiency, Leakey himself became the focus of a government probe. Moi eventually gutted KWS of its ability to keep the national parks secure, and Leakey resigned. It was during this period that his small plane crashed in the Great Rift Valley. Leakey acknowledges that he never liked to fly and was not a particularly good pilot, but the crash was widely reported as an assassination attempt.

Whatever drove Leakey's Cessna into the valley floor, there's no question that his successes have come at great cost. One gets the sense that he feels less wounded by his political opponents than by Kenya's aristocratic British community. In 1995, 88 of them publicly pledged their support to Moi after the president undercut Leakey's attempts to stem corruption. Among them was Richard's own brother Philip, a former member of Parliament.

After his ouster from the wildlife service, Leakey founded a reform political party, alienating many British settlers, who warned that he was jeopardizing their residence in the country. Despite death threats and even a public whipping by an angry mob linked to Moi's party, Leakey won a seat in Parliament in 1997. A year later, with international lenders withholding funds because of the nation's pervasive corruption, Moi asked Leakey to rejoin his administration. So Richard Leakey, five times accused of treason—and of being a racist, colonialist, and atheist (the only accusation to which he pleads guilty)—was named head of Kenya's Public Service.

"I became, after the president, the most important man in the country," Leakey tells me. "I was in control of the military, the air force, the police, the teachers, and I had oversight over development of the national budget. I had"—he pauses to clear his throat demurely—"considerable authority."

Considerable, yes. But perhaps not quite as much as he may have thought. After Leakey presented Moi with files detailing the illicit activities of 12 of the president's 15 top ministers, not one was prosecuted. Instead, a constitutional court threw out the law that had given Leakey power to fight corruption.

"So I quit," he says, then adds in a self-mocking tone, "because I no longer had my way."

After two kidney transplants, Leakey has the wry introspection of a man facing mortality. Looking beyond the span of his own life, he is trying to make sure that African conservationists and scientists have the same opportunities afforded their First World colleagues who work in Africa. Like most veteran conservationists here, Leakey believes that if the continent's wildlife is to be saved, it will be by Africans themselves.

Leakey and I talk well into the afternoon. The day is sunny and hot, but the glare is filtered through a net of leaves. Lunch is on order, and I ask about washing my hands.

"Make sure you latch the door after you come out," Leakey says as he points me to the restroom. "We had a green mamba in there." He looks mildly disappointed when I don't shudder with fear.

When I return, we talk about one of Leakey's recent eureka moments, which happened not among acacia trees and lions but on San Francisco Bay, while sailing with friends who work in the world of Internet advertising. The result was the 2005 launch

of WildlifeDirect, a Web site where conservationists and field biologists in such remote spots as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sumatra blog about their work, their daily activities, and the lives (and deaths) of the animals they are struggling to save. Part Hotel Rwanda, part Charlotte's Web, part 1970s-style swashbuckling journalism, WildlifeDirect exudes raw emotion, and its readers are asked to donate directly to the site's various causes. The big news: It's working. In 2008, funds from WildlifeDirect and the European Union supplied salaries and equipment for 700 park rangers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A major selling point for the site is that every dollar goes directly to the conservationists. Leakey makes that possible by using his marquee name to raise funds for operational expenses.

"Was this meant as an implicit criticism of the big international conservation organizations?" I ask. "Groups that have a lot of overhead?"

"Explicit," he says, grinning.

As a young man, Leakey bucked his father's opinion about the most promising place to dig for fossils and ended up making one of paleontology's major discoveries. As an older man, he still shuns conventional wisdom. A favorite mantra is "Never be afraid to admit you're wrong."

In 2007, despite having sworn off politics, Leakey came up with an idea that wasn't just innovative; it was shocking. He called for the dissolution of the Kenya Wildlife Service—the organization he'd once overseen—and for privatizing management of the country's national parks.

"In this country the private sector does very well," he tells me. "The public sector does abysmally. To have a stable government, you first need a level of personal economic security or food security or health security—or ideally a combination of all of these. We're simply not there."

On this dispiriting note, we adjourn to a long wooden table for lunch. Leakey urges me to try the lettuce he grew on his farm outside Nairobi, promptly refills my wineglass with Cotes du Rhone, offers fatherly advice about my love life, and brags about the homemade butter, cheese, and wonderfully textured whole wheat bread.

I recall that Leakey started his career as a safari guide, and he clearly enjoys the role of host. He famously never finished high school, and the occasional odd bitter joke suggests that a sense of intellectual inferiority instilled by his father has not entirely disappeared. Yet his thinking on conservation is trenchant. Like conservationists throughout the developing world, Leakey is wondering how to preserve nature when civil society is weak.

I ask him if he sees a fundamental relationship between democracy and protecting the environment.

"Democracy itself is probably somewhat of a misnomer," Leakey says, choosing his words carefully. "Accountability is the desired condition of civil society. If you have accountability, you move toward a greater democratic space. But if you have greater democratic space, you will not necessarily move to greater accountability."

My question, I realize, derives from a U.S. perspective. In Kenya, "democracy" is a cultural graft with a dubious history and an uncertain prognosis. But even here, Leakey argues, in a land where the future of Western-style democratic institutions is unclear, the connection between humans and nature can still prevail.

When Louis Leakey died, he was eulogized as a "true son of Kenya." The same could be said of Richard, whose dedication to his homeland may be the one pure and uncomplicated thing in his life. Although he's used white privilege and the Leakey name to spectacularly good effect, he has also openly defied those Kenyans who tried to quiet him in hopes of maintaining their own privileged existence amid Kenya's increasingly desperate poverty.

Richard Leakey's most lasting achievement may turn out to be the extraordinary number of black African scientists and conservationists who have benefited from his assistance while establishing their careers. One gray-haired Kenyan professor told me that as a struggling graduate student, he had been unable to conduct field research for his dissertation until Leakey loaned him a Land Rover. As a faculty member at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, Leakey is overseeing the construction of three Rift Valley research stations that will provide young African scientists with the same level of institutional support enjoyed by their U.S. and European counterparts.

Simiyu Wandibba, the second black Kenyan to earn a Ph.D., once told me that he had nursed a grudge after Leakey had failed to appoint him as his successor at the National Museums of Kenya. Leakey had surrounded himself with yes-men, Wandibba said, to the detriment of both the museums and the Kenya Wildlife Service. Wandibba went on to become a university professor, but for decades Leakey's decision had rankled.

"Very few people admit their mistakes," Wandibba said. "A few years ago, when Richard went to teach at Stony Brook, he said, 'I've wronged that man.' He told me that. When he established the Turkana Basin Institute, he asked if I would become a trustee, and I said yes."

We were standing on a crowded terrace, but as Wandibba leaned forward, looking directly into my eyes, the chatter around us receded.

"What we say in this patriarchal language," he said, "we fight as men."

Susan Zakin is the author of several books on the environment, most recently In Katrina's Wake: Portraits of Loss From an Unnatural Disaster. She lives part-time in Kenya.

Photos from top left: Sara Stathas; iStockphoto/GomezDavid; Jonathan and Angela Scott/NHPA/Photoshot (Leakey in front of ivory fire); Christopher Cormack/Corbis (Leakey with skull); Nation Media Group—Nairobi