sierraclub.org - sierra magazine - january/february 2010 - grapple

Grapple | With Issues and Ideas

Liberating the Klamath | Up to Speed | Groundhog Ways | Reaping the Wind |

As the World Warms | Woe Is Us | Buggy Shangri-La

Liberating the Klamath

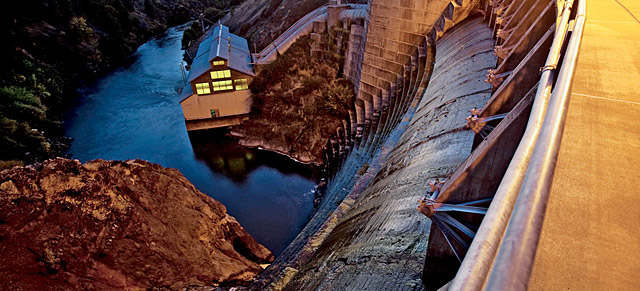

An agreement to remove fish-blocking dams signals new hope for Pacific salmon

One of four dams on the Klamath River scheduled to come down by 2020.

For centuries, the salmon run along the Klamath River in Oregon and California was so bountiful that the Karuk, Klamath, Hoopa Valley, and Yurok tribes could harvest the fish almost year-round. Starting in 1911, four dams went up, cutting off some 300 miles of prime spawning ground. The Karuk fishery is now limited to three weeks a year, while the Klamath tribes, despite treaty rights to the fish, haven't seen a salmon on their stretch of the river in 90 years.

In what may be the biggest river-restoration agreement in history, PacifiCorp, the utility that owns the dams, says it will remove them by 2020. The decision follows years of negotiation between native tribes, utilities, environmentalists, fishing groups, farmers, and government regulators. The agreement was expected to be signed in December.

Eight years ago, 33,000 mature chinook and endangered coho salmon died along the river when the Bush administration ignored federal biologists' warnings and diverted flows for irrigation. This so diminished salmon runs that commercial fishing has been shut down along the Oregon-California coast since 2006. In 2007 and 2008, tribal leaders showed up at the shareholder meeting of PacifiCorp's parent company, Berkshire Hathaway, to confront CEO Warren Buffett. And as the dams' licenses came up for renewal, federal regulators started piling on conditions, demanding $320 million for fish screens and fish ladders. The dams began looking like a poor investment.

"At the end of the day, this is a business decision by PacifiCorp," explains Steve Rothert, director of the California office of American Rivers, which helped make the case for the dam removal.

While unfettered flows are still a decade away, a companion agreement will raise water levels in the interim and commit PacifiCorp to spending $500,000 a year on habitat restoration along the Klamath's tributaries. This is an enormous change; for decades, salmon have been last in line for water and have been given only what was necessary to prevent extinction—if that. "Our goal is a harvestable surplus of fish," says Craig Tucker, spokesman for the Karuk tribes. "We don't want these fish on the endangered species list. We want them in the smokehouses." —Dashka Slater

Groundhog Ways

When Punxsutawney Phil sees his shadow on February 2—or not—the nation will admire his meteorological sagacity. Recent advances in groundhogology have uncovered the basis of Phil's powers: lipid metabolism and biochemistry.

When Punxsutawney Phil sees his shadow on February 2—or not—the nation will admire his meteorological sagacity. Recent advances in groundhogology have uncovered the basis of Phil's powers: lipid metabolism and biochemistry.

It turns out that groundhogs (Marmota monax) control their hibernation through a select diet of polyunsaturated fatty acids. They gorge on leafy plants, seeds, and nuts during spring and summer. Around October, they start to decrease their body temperature to as low as 41 degrees and their metabolic rate to as low as 1 percent of normal.

Rather than waste energy looking for food in the snow, the rodents draw on a special type of brown fatty tissue in their back and shoulders for winter nutrition. By February, those metabolic stores are nearly exhausted, and groundhogs have lost as much as half of their body mass. Should the weather start to warm, a surge in linolenic acid breaks their torpor. If, on venturing outside their burrow, they find it's still winter, they may return to full hibernation several times, like sleepers hitting the snooze button. —Thomas P. Mahoney and Paul Rauber

Reaping the Wind

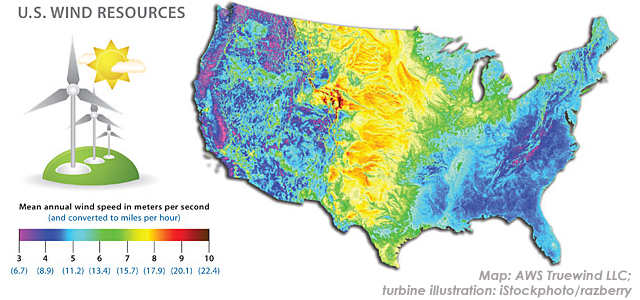

Source: AWS Truewind LLC; turbine illustration: iStockphoto/razberry

You may not need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows, but anyone planning to build a wind farm does. The map below, developed by the renewable-energy consulting firm AWS Truewind, shows wind speed at 80 meters (260 feet) above the ground, the height of a typical modern wind tower. Most obvious here is that the Great Plains hold the potential to be the country's "wind basket."

The reason, explains AWS Truewind chief meteorologist Michael Markus, is their famous flatness and "low surface roughness"—i.e., lack of geological features to impede wind flow. Also, as the storms that form in the lee of the Rocky Mountains move east, they are preceded by strong southerlies and followed by strong northwesterlies. All can be put to work to create carbon-free power. —P.R.

AS THE WORLD WARMS

Quick thinking before we slowly fry

End of the Line The Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern Railroad Corporation has shelved plans to build a 278-mile rail line to carry coal from Wyoming's Powder River Basin to coal-fired power plants in the upper Midwest. The tracks would have carried 100 million tons of coal a year, enough to power 50 plants. The Sierra Club has fought the plan for nine years, but DM&E blamed the "economic climate," not the planetary one, for its decision.

Not our chamber Fed up with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce's retrograde views on climate change—it recently called for a new "Scopes monkey trial" on the underlying science—a host of member companies headed for the exit. Nike gave up its seat on the chamber's board, and Apple, Exelon, California's Pacific Gas and Electric, and New Mexico utility PNM Resources called it quits. Even General Electric distanced itself from the group, saying that "the chamber does not speak for us on climate legislation."

Condom Nation A London School of Economics study has concluded that the most cost-effective place to fight carbon emissions is in the bedroom. Investing in family planning can reduce emissions at a bargain rate of $7 per ton, while traditional avenues like green technology cost $32 per ton. The figures are based on providing birth control to married women who want it but don't have access. If willing unmarried women were included, the impact would be even greater. —D.S.

ON THE ONE HAND . . .

Healthcare reformers might want to look into buildings with Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification. In a study of 154 LEED-certified and Energy Star-rated office buildings, 45 percent of the tenants responding reported taking fewer sick days since moving into their green digs, and 54 percent felt more productive. "When buildings are LEED certified, they tend to have more daylight, better ventilation, and cleaner air," explained study coauthor Norm Miller of the University of San Diego. "Apparently it has an impact."

ON THE OTHER . . .

The nonprofit U.S. Green Building Council, which developed the LEED standards, recently looked at the energy performance of 121 LEED-certified office buildings. Less than half qualified for the EPA's Energy Star rating, indicating that many are not significantly more energy efficient than conventional structures; in fact, a quarter of the LEED-certified buildings were less efficient. Critics say LEED's checklist approach to design encourages easy green add-ons like bike racks and bamboo flooring while shortchanging more effective (but expensive) investments in efficient heating, cooling, and electricity use. So far there are no plans to "deLEEDify" the energy hogs. —D.S.

Woe Is Us: Ready, set, panic.

SNAKES ON PLAINS

SNAKES ON PLAINS

The good news from a recent U.S. Geological Survey report is that of the nine "high-risk species" of invasive giant snakes that are already established in the United States or might soon be, "most . . . would not be large enough to consider a person as suitable prey."

That leaves some pet-store fugitives that might. Reticulated pythons, which can exceed 26 feet in length and are "the snake most associated with unprovoked human fatalities in the wild," have been sighted or captured in south Florida, as have various species of anaconda. At least they aren't known to have established breeding populations yet, like the tens of thousands of Burmese pythons and boa constrictors that have spread across much of south Florida. Other potential habitats are south Texas, Hawaii, and America's tropical islands. But, cautions the USGS's risk assessment, "many other areas with mild winters are potentially vulnerable to colonization by at least one of the giant constrictors." And don't think you're safe if you don't live in a swamp: The snakes are "quite tolerant of urban or suburban areas."

Still, the danger to humans from these snakes is about on par with that from alligators. Native birds and small mammals are most at risk. Within 40 years after the brown tree snake was introduced to Guam, it had eliminated most native birds, lizards, and bats. So you might want to keep an eye on your pets, especially puppies and kittens. "Losses of caged birds," notes the USGS report, "are generally a one-off affair, as the snake is often unable to depart between the cage wires due to its excessively bulging stomach." —P.R.

Buggy Shangri-La:

Western winters are no longer cold enough to kill hungry beetles

A tiny beetle ordinarily kept in check by extreme cold is devastating lodgepole pine forests in the western United States and Canada, thanks to warmer winters in those areas. Nearly 2 million acres of trees have been devoured by the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) in Colorado alone since 1996. "We can probably expect to lose 90 percent of the larger lodgepole pine trees in Colorado within the next five years," said Joe Duda, a forest management supervisor at the Colorado State Forest Service.

No exotic invader, the beetles are native to the pine forests, and it's normal for their populations to periodically explode. "But this epidemic is larger than any we've seen since the West was settled," said U.S. Forest Service spokesperson Mary Ann Chambers. Typically, beetle populations are reduced by very cold winters, when temperatures can drop below minus 40 degrees. (The beetles survive lesser cold spells by essentially making their own antifreeze.) But balmier winters in the West have created a beetle Shangri-la. "Because of the warm winters, they just keep multiplying," said Chambers. Persistent drought has also weakened the pines' ability to make protective sap, which keeps the beetles at bay.

It's not just global warming that's to blame. In the late 1800s, vast numbers of trees were cut down for mining works and other frontier developments. The sprouts that replaced them are now large swaths of fully mature trees—the beetles' favorite dish.

The current epidemic will eventually run its course, and the forests will regrow. In the meantime, millions of acres of dead trees increase the danger of wildfire. "Most of the dead trees will fall within 12 years," said Chambers. "So we'll have about 2 million acres of flammable pick-up sticks."

—Laurie J. Schmidt

Photos and illustrations, from top: David McLain/Aurora Photos; Mark Graf; Peter and Maria Hoey; John Ueland